document.querySelector('video').playbackRate = 1.2“Now, if someone tries to monopolize the Web,

for example pushes proprietary variations on network protocols,

then that would make me unhappy.”

- Tim Berners-Lee

https://www.accessnow.org/keepiton/ (good animation no

longer posted).

https://www.accessnow.org/elections-internet-shutdowns-watch-2022/

https://www.accessnow.org/cms/assets/uploads/2022/06/A-taxonomy-of-internet-shutdowns-the-technologies-behind-network-interference.pdf

Review methods.

https://www.theregister.com/2022/10/06/great_firewall_of_china_upgrades/

https://www.pcmag.com/news/russia-tests-cutting-off-access-to-global-web-and-vpns-cant-get-around

https://www.encryptallthethings.net/

and as many layers as you can,

ideally, from the IP-layer, all the way up,

via IPSec.

Review by glancing back now at section on encapsulation and

layering:

Overview.html

Reading:

Book

3.1-3.2

IntroNetworks

http://intronetworks.cs.luc.edu/current2/uhtml/intro.html#transport

Computer-Networking

https://www.computer-networking.info/1st/html/transport/principles.html

https://www.computer-networking.info/2nd/html/protocols/transport.html

Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transport_layer

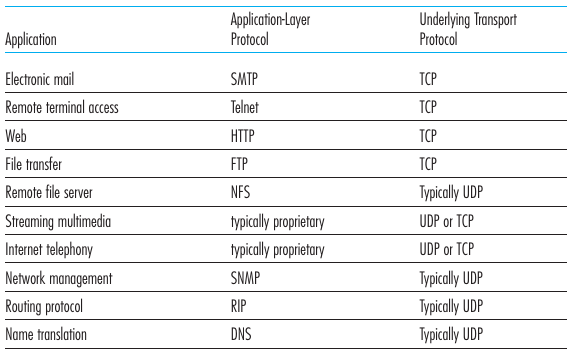

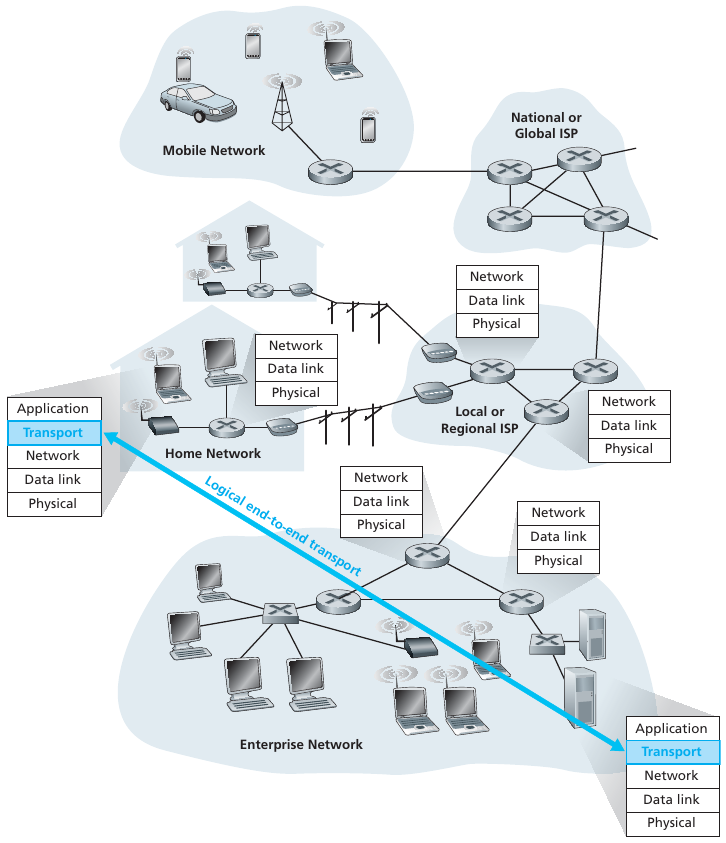

Application usage of transport layer protocols

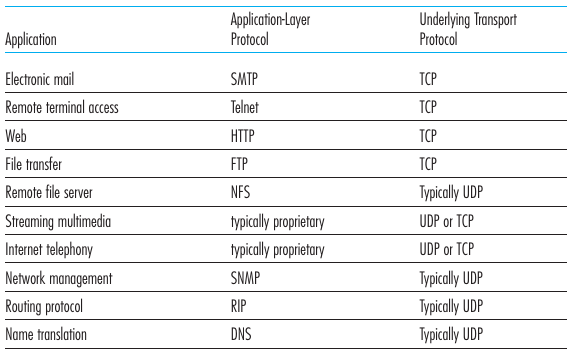

Transport layer is more than TCP and UDP

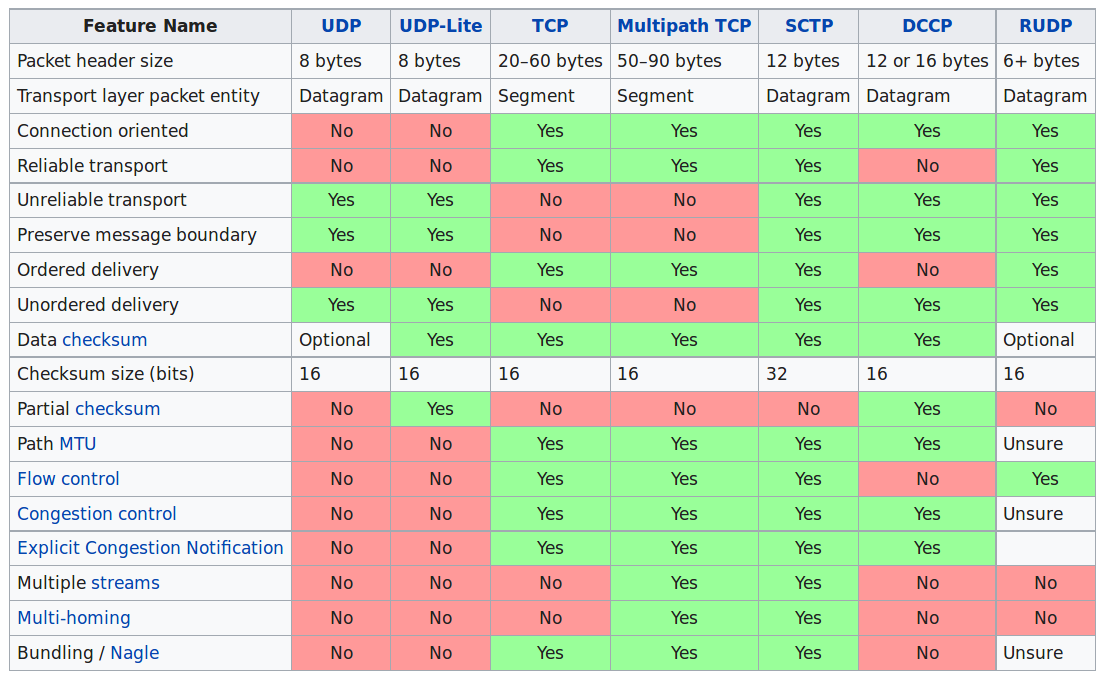

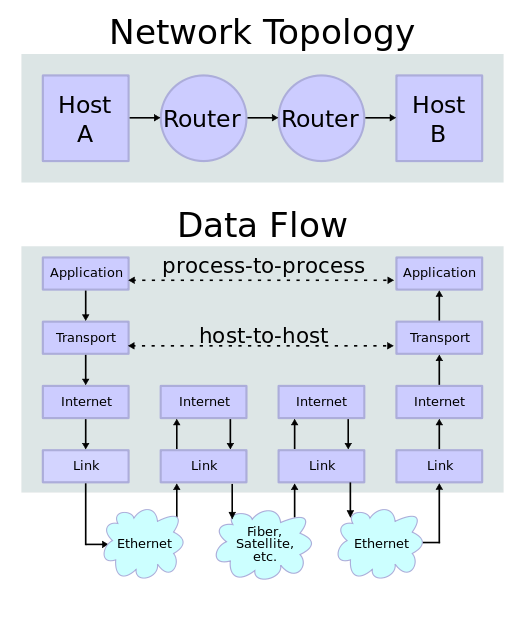

Application and network layers are end-end

Note: Transport facilitates process-to-process connections.

Transport layer services are conveyed to an application via a programming interface to the transport layer protocols.

Multiplexing:

Connection-oriented communication:

It is normally easier for an application to interpret a connection as a

data stream rather than having to deal with the underlying

connection-less models, such as the datagram model of the User Datagram

Protocol (UDP) and of the Internet Protocol (IP).

Same order delivery:

Reliability:

Flow control:

Congestion avoidance:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Port_(computer_networking)

In computer networking, a port is a communication

endpoint.

At the software level, within an operating system,

a port is a logical construct that identifies a

specific process or a type of network service.

https://www.homenethowto.com/advanced-topics/ports-tcp-and-udp-in-depth/

Each port number is a 16-bit number, ranging from 0 to 65535.

The port numbers ranging from 0 to 1023 are called well-known port numbers and are restricted, which means that they are reserved for use by well-known application protocols such as

At the software level, within an operating system, a port is a logical construct that identifies a specific process or a type of network service.

The list of well-known port numbers is given in RFC 1700 and is updated at

Check out on Linux:

$ vimx /etc/servicesAs the port numbers are encoded as a 16 bits field, there can be up to only 65535 different server processes that are bound to a different UDP port at the same time on a given server.

Privileged port numbers

(1 < port < 1024)

In most Unix variants, only processes having system administrator

privileges can be bound to port numbers smaller than 1024.

Ephemeral port numbers

(officially 49152 <= port <= 65535)

Registered port numbers

(officially 1024 <= port < 49152)

Port numbers are sometimes seen in web or other uniform resource

locators (URLs).

By default, HTTP uses port 80 and HTTPS uses port 443,

but a URL like http://www.example.com:8080/path/

specifies that the web browser connects instead to port 8080 of the HTTP

server.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Port_scanner

https://nmap.org/book/tcpip-ref.html

sudo apt/dnf/zypper/etc install nmap+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Cahoot-03-0

nmap web.mst.edu

Watch this with Wireshark

Mention:

https://shodan.io

does extensive port-scanning

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Port_scanner#Types

TCP scan

SYN scan

UDP scan

ACK scan

Window scan

FIN scan

and more…

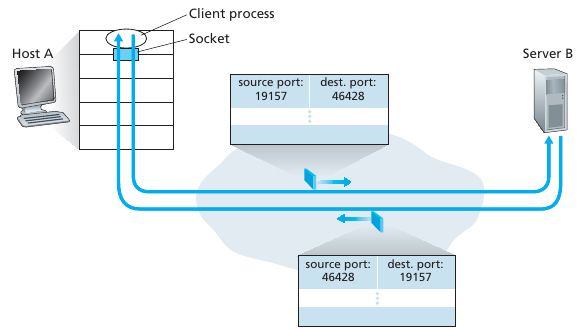

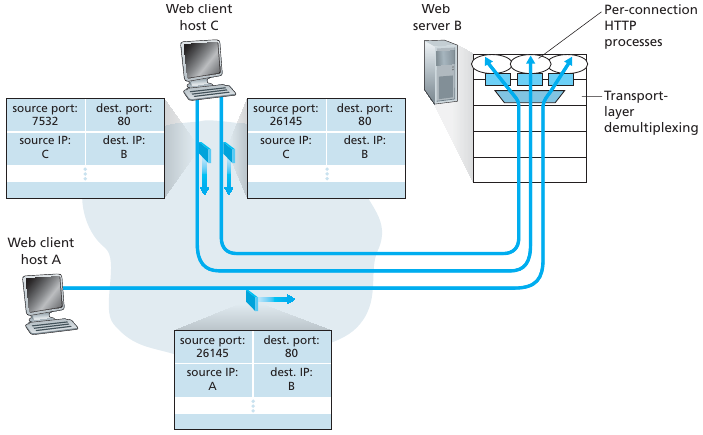

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multiplexing

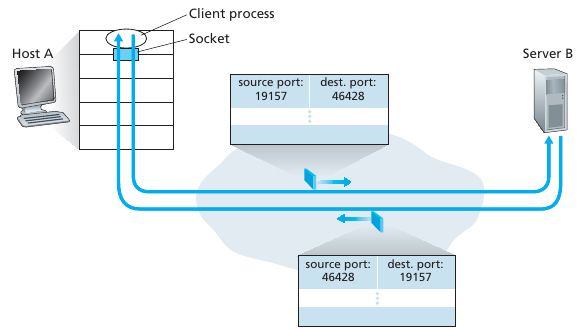

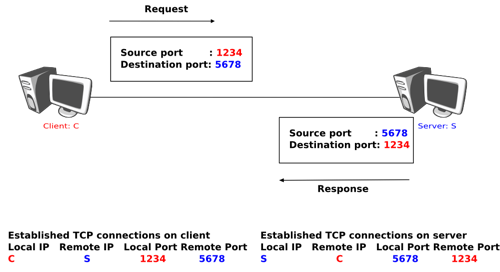

Multiplexing at the transport layer refers merely to the mixing and un-mixing of traffic with different (port, IP) tuples for source and destination addresses.

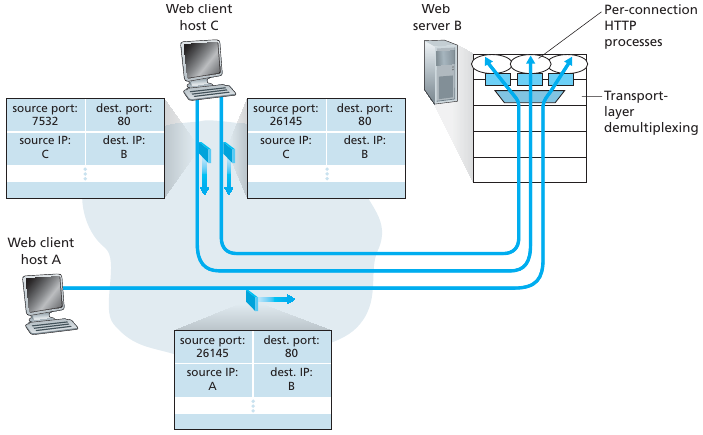

Transport-layer multiplexing and de-multiplexing

Web server and two clients

While destination (IP, port) tuples are the same, the source (IP, port)

tuples differ for each client.

Handle data from multiple sockets,

add transport header including source (IP, port) tuple,

and destination (IP, port) tuple,

used for de-multiplexing at the destination,

and on response back to the source.

Use header info to deliver received segments to correct process, and correct socket within the process.

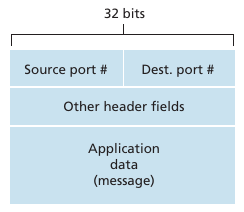

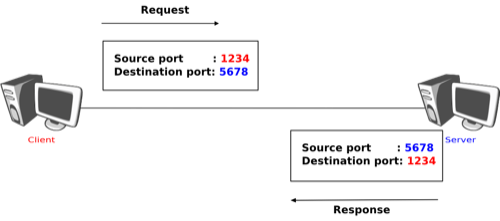

Source and destination port-numbers in segment

I heard a great UDP joke the other day….

You might not get it.

Reading:

Book

Chapter 3.3-3.4

IntroNetworks

http://intronetworks.cs.luc.edu/current2/uhtml/udp.html

Computer-Networking

https://www.computer-networking.info/1st/html/transport/udp.html

https://www.computer-networking.info/2nd/html/protocols/udp.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User_Datagram_Protocol

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datagram_Transport_Layer_Security

(UDP encryption)

IETF

https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc768

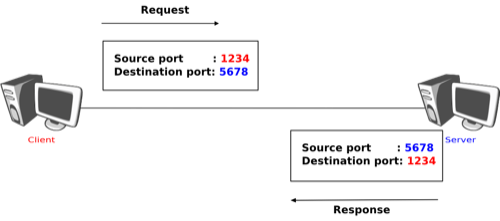

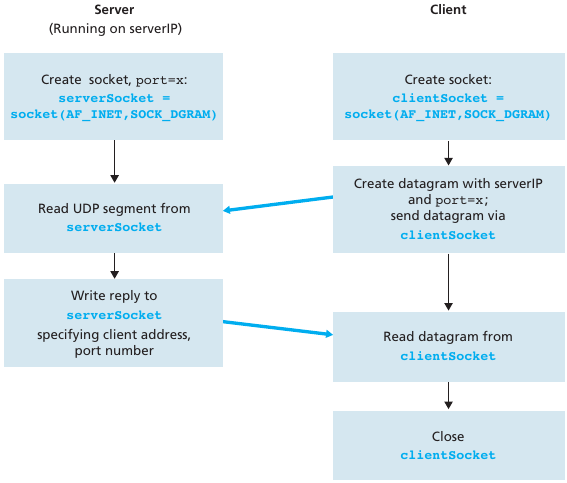

recall: when creating datagram to send into UDP socket,

must specify destination IP address destination port #

The best thing about UDP jokes is that I don’t care if you get them or not.

I had another funny UDP joke to tell,

but I lost it somewhere…

Reminder:

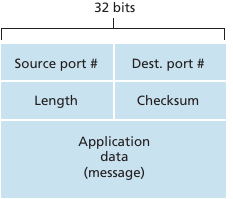

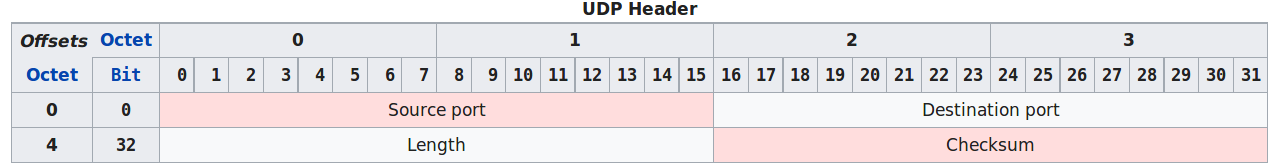

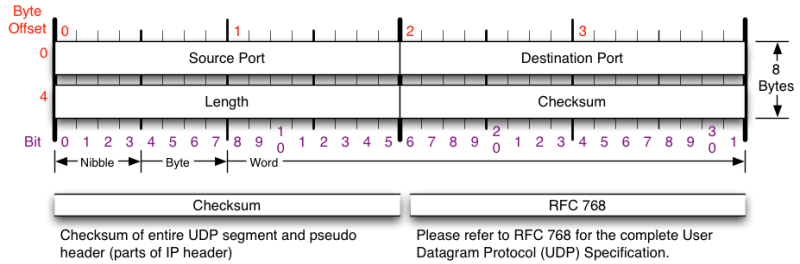

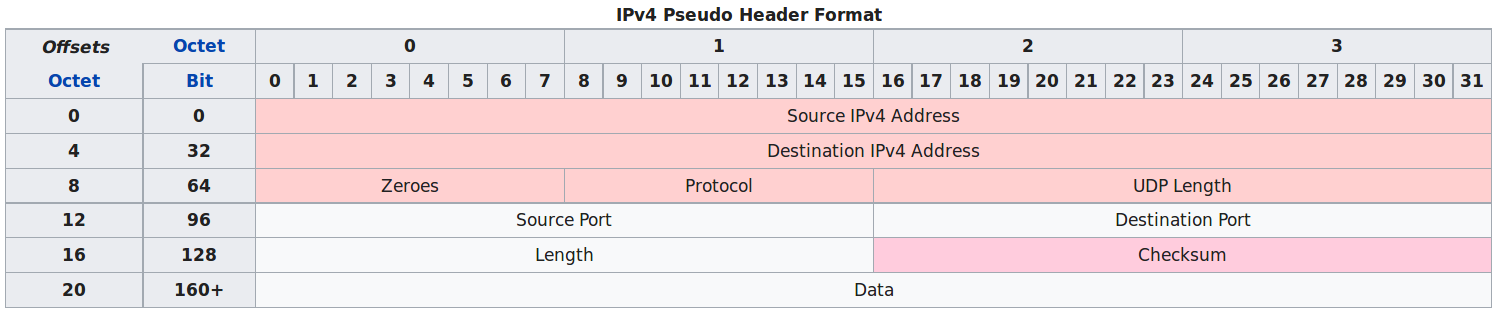

UDP segment structure:

* The UDP header contains four fields:

* a 16 bits source port

* a 16 bits destination port

* a 16 bits length field

* a 16 bits checksum

Source port number:

Sender’s port; should be assumed to be the port to reply to if

needed.

If the source host is the client,

then the port number is likely to be an ephemeral port number.

If the source host is the server,

then the port number is likely to be a well-known port number.

Destination port number:

Receiver’s port is required.

Similar to source port number, if the client is the destination

host,

then the port number will likely be an ephemeral port number,

and if the destination host is the server,

then the port number will likely be a well-known port number.

Length:

Specifies the length in bytes of the UDP header and UDP data.

The minimum length is 8 bytes because that is the length of the

header.

Data length, which is imposed by the underlying IPv4 protocol,

is 65,507 bytes (65,535 - 8 byte UDP header - 20 byte IP header).

Checksum:

May be used for error-checking of the header and data.

This field is optional in IPv4, and mandatory in IPv6.

The field carries all-zeros if unused.

I’d make another joke about UDP,

but I don’t know if anyone’s actually listening…

Goal: detect “errors” (e.g., flipped bits) in transmitted segment

http://intronetworks.cs.luc.edu/current2/uhtml/packets.html#error-detection

* You may wonder why UDP provides a checksum in the first place, as many

link layer protocols (including the popular Ethernet protocol) also

provide error checking.

* There is no guarantee that all the links between source and

destination provide error checking

* one of the links may use a link-layer protocol that does not provide

error checking.

* Even if segments are correctly transferred across a link, it’s

possible that bit errors could be introduced when a segment is stored in

a router’s memory.

* Given that neither link-by-link reliability nor in-memory error

detection is guaranteed, UDP must provide error detection at the

transport layer, on an end-end basis, if the end-end data transfer

service is to provide error detection.

* The checksum at this level is an example of the celebrated end-end

principle in system design [Saltzer 1984], which states that since

certain functionality (error detection, in this case) should be

implemented on an end-end basis:

* “functions placed at the lower levels may be redundant or of little

value when compared to the cost of providing them at the higher

level.”

* UDP does not do anything to recover from an error.

* Some implementations of UDP simply discard the damaged segment; others

pass the damaged segment to the application with a warning.

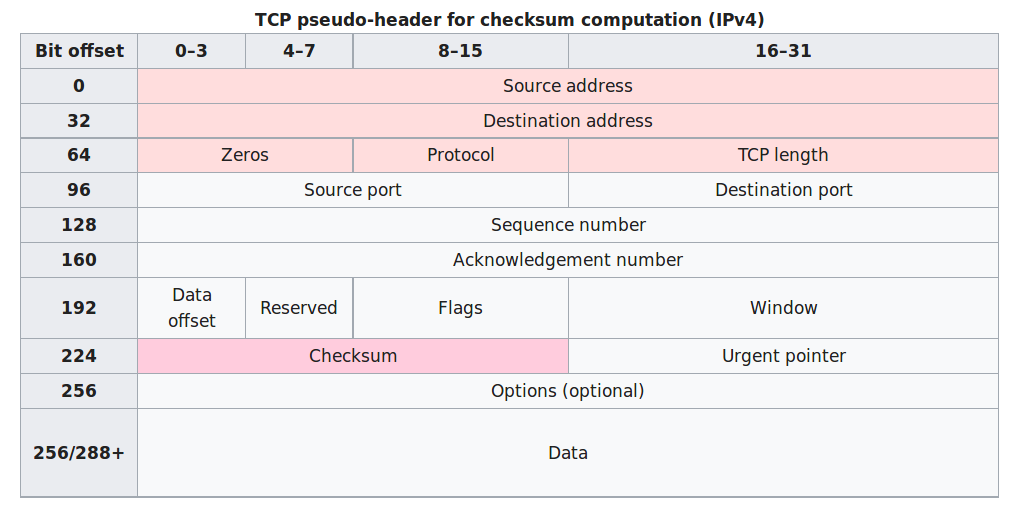

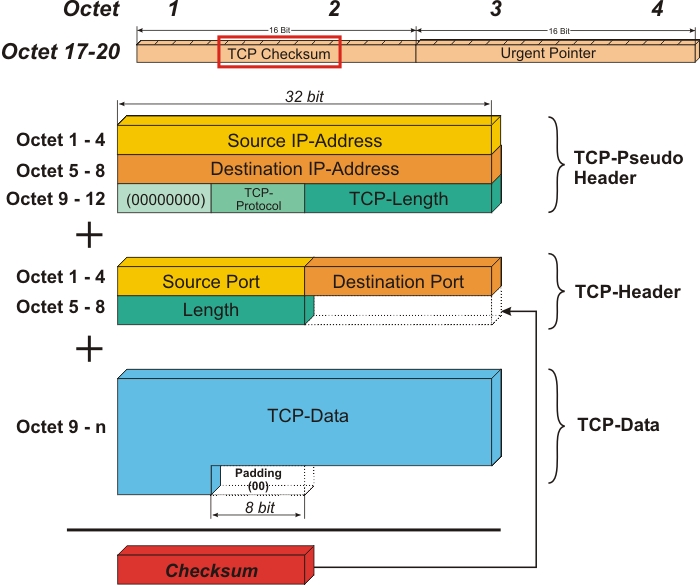

Pseudo-header the checksum is taken over:

* The source and destination addresses are those in the IPv4

header.

* The protocol is that for UDP (see List of IP protocol numbers): 17

(0x11).

* The UDP length field is the length of the UDP header and data. The

field data stands for the transmitted data.

* UDP checksum computation is optional for IPv4.

* If a checksum is not used it should be set to the value zero.

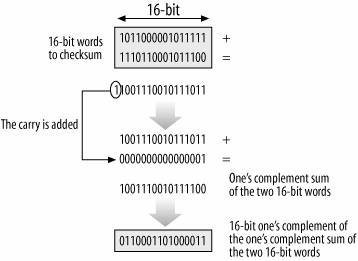

* Checksum uses the 1s complement: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ones%27_complement

* 1s complement of the sum of all the 16-bit words in the segment, such

that adding back the checksum to the same input will produce

111111111…

* The ones’ complement of a binary number is defined as the value

obtained by inverting all the bits in the binary representation of the

number (swapping 0s for 1s and vice versa).

* The ones’ complement of the number then behaves like the negative of

the original number in some arithmetic operations.

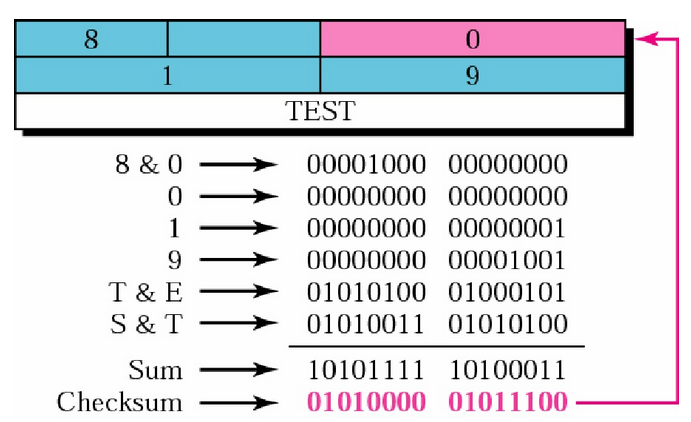

As an example, suppose that we have the following three 16-bit words:

0110011001100000

0101010101010101

1000111100001100The sum of first two of these 16-bit words is

0110011001100000

0101010101010101

__________

1011101110110101Adding the third word to the above sum gives

1011101110110101

1000111100001100

__________

0100101011000010The checksum of the UDP segment is computed over a pseudo header

containing:

the source IP address,

the destination IP address and

a 32 bits bit field containing the most significant byte set to 0,

the second set to 17,

and the length of the UDP segment in the lower two bytes.

the entire UDP segment, including its header

Ask:

UDP checksum pseudo header includes IP addresses (which are normally in

network layer), why?

+++++++++++++++++++++++ Cahoot-03-1

Are any others of these disadvantages?

If we assume there are bad network citizens?

I once told an NTP joke.

The timing was perfect…

The punchline often arrives before the set-up.

Do you know the problem with UDP jokes?

+++++++++++++++++++++++ Cahoot-03-2

nc (netcat) can also serve to explore UDP functionality (-u is

udp)

$ nc -u serverurl

Re-demonstrate with Wireshark:

socket_UDP_server.py, socket_UDP_client.py, nc -u, nslookup

Let’s begin to think about TCP:

Re-demonstrate with Wireshark:

socket_TCP_server_mt.py, socket_TCP_client_mt.py, ncat, traceroute, web

browser, ncat

Some things to observe:

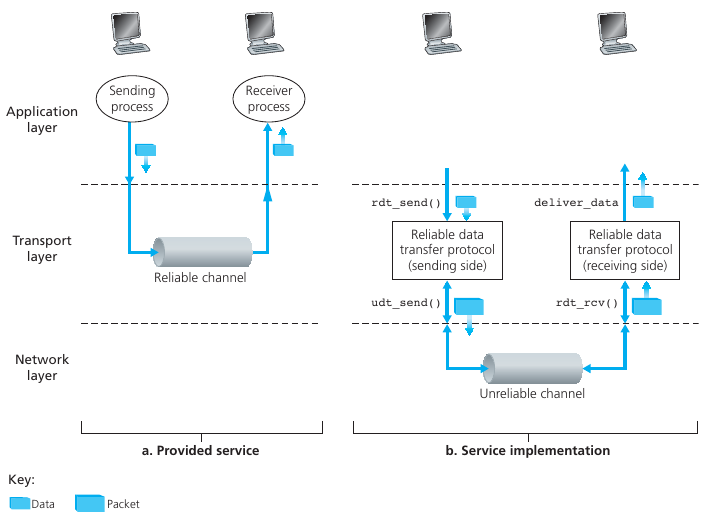

(theory)

Reliable data transfer

How to implement the black frames boxes above?

Checksum

Used to detect bit errors in a transmitted packet.

Timer (timeout)

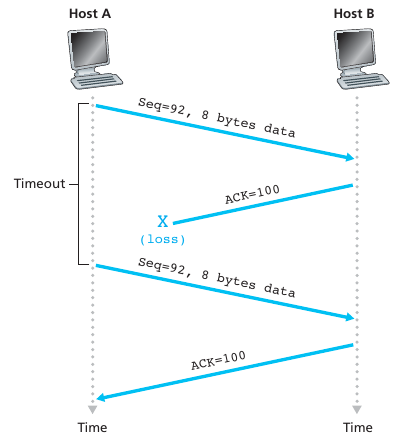

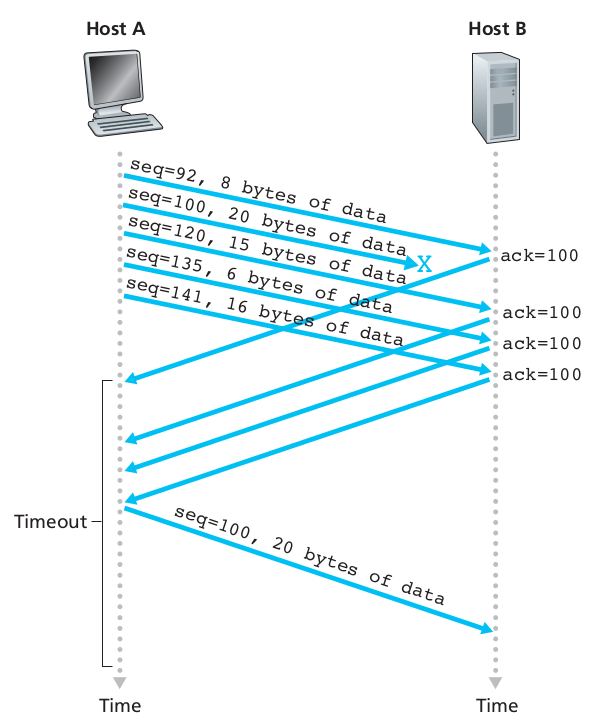

Used to timeout/re-transmit a packet, possibly because the packet (or

its ACK) was lost within the channel.

Because timeouts can occur when a packet is delayed but not lost

(premature timeout),

or when a packet has been received by the receiver, but the

receiver-to-sender ACK has been lost,

duplicate copies of a packet may be received by a receiver.

Sequence number

Used for sequential numbering of packets of data flowing from sender to

receiver.

Gaps in the sequence numbers of received packets allow the receiver to

detect a lost packet.

Packets with duplicate sequence numbers allow the receiver to detect

duplicate copies of a packet.

Acknowledgment

Used by the receiver to tell the sender that a packet or set of packets

has been received correctly.

Acknowledgments will typically carry the sequence number of the packet

or packets being acknowledged. Acknowledgments may be individual or

cumulative, depending on the protocol.

Negative acknowledgment

Used by the receiver to tell the sender that a packet has not been

received correctly.

Negative acknowledgments will typically carry the sequence number of the

packet that was not received correctly.

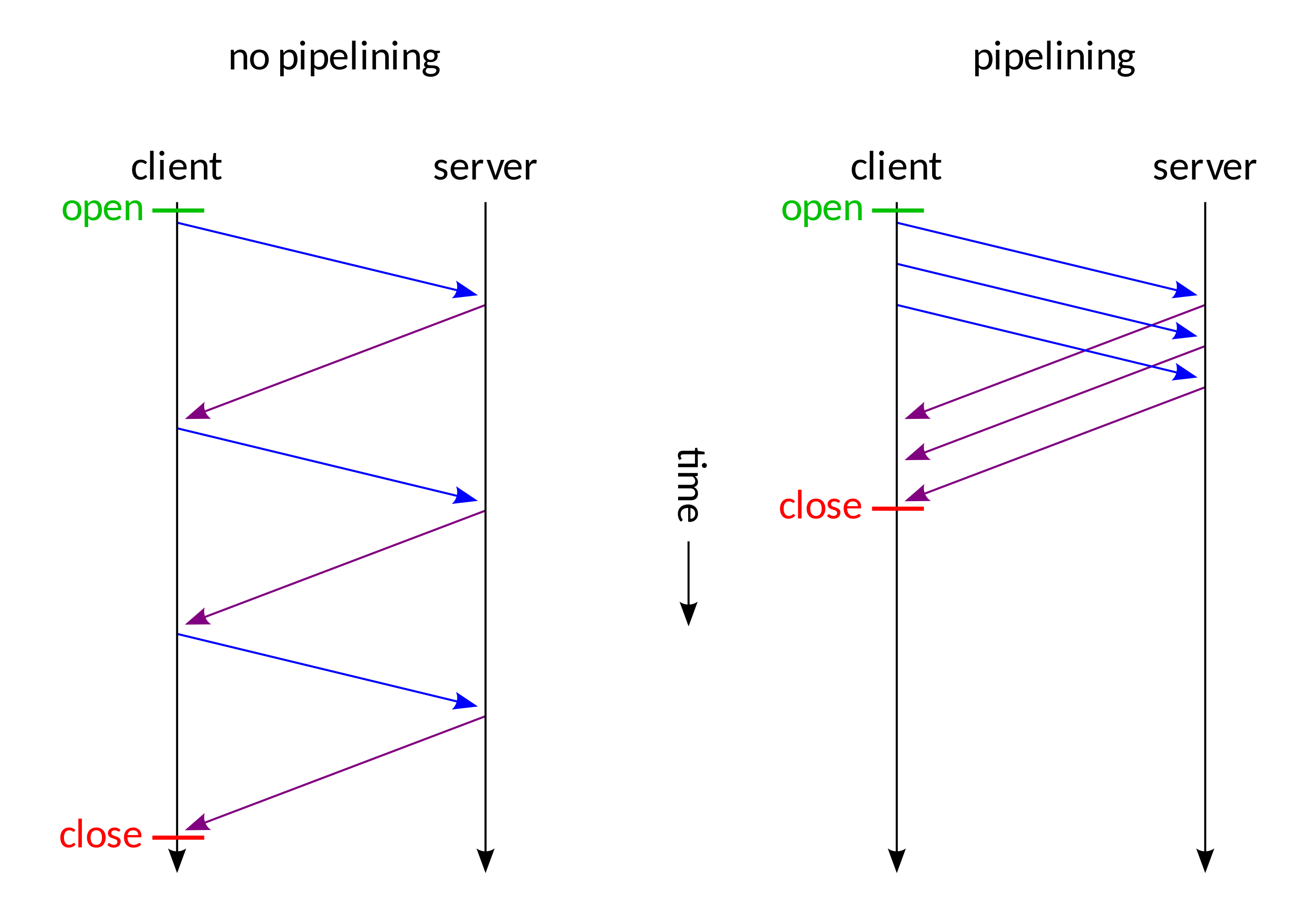

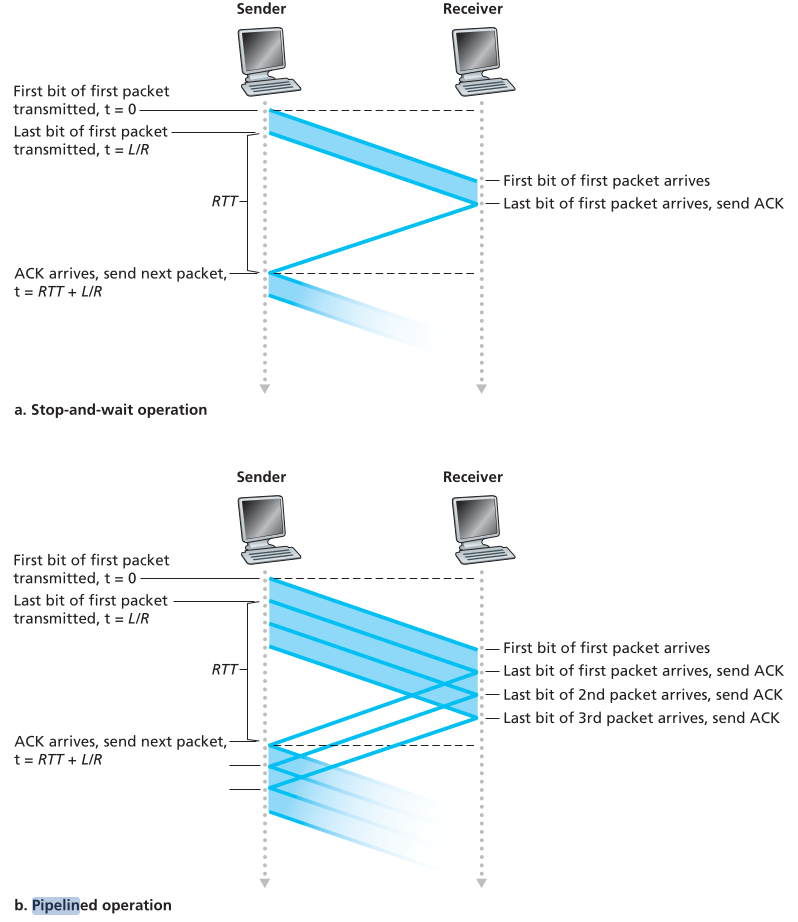

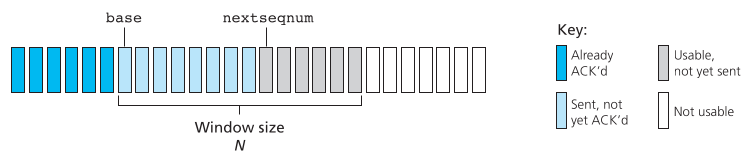

Window, pipelining

Note: These two are more like speed-enhancing mechanisms for

compensating for reliability mechanisms.

The sender may be restricted to sending only packets with sequence

numbers that fall within a given range.

By allowing multiple packets to be transmitted but not yet acknowledged,

sender utilization can be increased over a stop-and-wait mode of

operation.

We’ll see shortly that the window size may be set on the basis of the

receiver’s ability to receive and buffer messages, or the level of

congestion in the network, or both.

More to come in protocol operation (below).

This is about how the next part covering TCP will feel:

“Hi, I’d like to hear a TCP joke”

“Hello, would you like to hear a TCP joke”

“Yes, I’d like to hear a TCP joke”

“OK, I’ll tell you a TCP joke”

“OK, I’ll hear a TCP joke”

“Are you ready to hear a TCP joke”

“Yes, I’m ready hear a TCP joke”

“OK, I’m about to send a TCP joke. It will last 10 seconds, it has two

characters, it doesn’t have a setting, it ends with a punchline”

“Ok, I’m ready to hear a TCP joke that will last 10 seconds, has two

characters, has no explicit setting and ends with a punchline”

“I’m sorry, your connection has timed out,

… Hello, Would you like to hear a TCP joke”

Reading:

Book

Chapter 3.5-3.8

IntroNetworks

http://intronetworks.cs.luc.edu/current2/uhtml/

http://intronetworks.cs.luc.edu/current2/uhtml/tcpA.html

(read)

http://intronetworks.cs.luc.edu/current2/uhtml/tcpB.html

http://intronetworks.cs.luc.edu/current2/uhtml/reno.html

http://intronetworks.cs.luc.edu/current2/uhtml/dynamicsA.html

http://intronetworks.cs.luc.edu/current2/uhtml/dynamicsB.html

http://intronetworks.cs.luc.edu/current2/uhtml/newtcps.html

Computer-Networking

https://www.computer-networking.info/1st/html/transport/tcp.html

https://www.computer-networking.info/2nd/html/protocols/tcp.html

Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transmission_Control_Protocol

IETF

https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc7414

RFCs: 793, 1122, 1323, 2018, 2581

Demos

https://media.pearsoncmg.com/aw/ecs_kurose_compnetwork_7/cw/content/interactiveanimations/go-back-n-protocol/index.html|go-back-n

https://media.pearsoncmg.com/aw/ecs_kurose_compnetwork_7/cw/content/interactiveanimations/selective-repeat-protocol/index.html

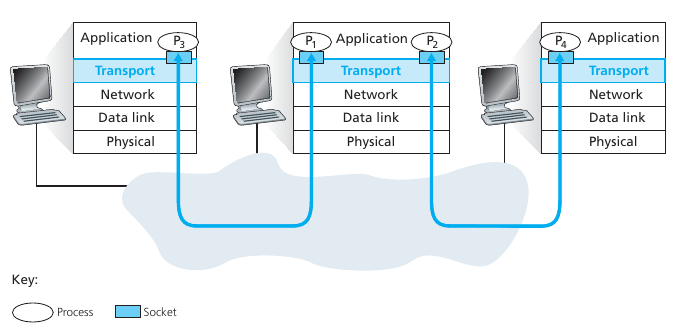

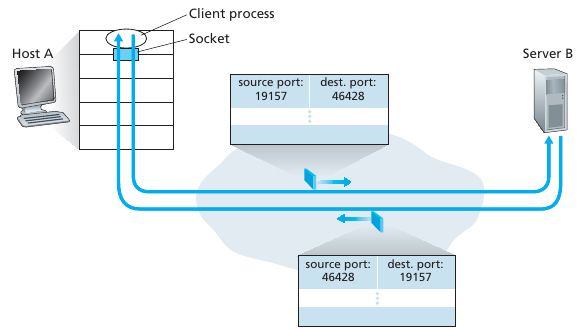

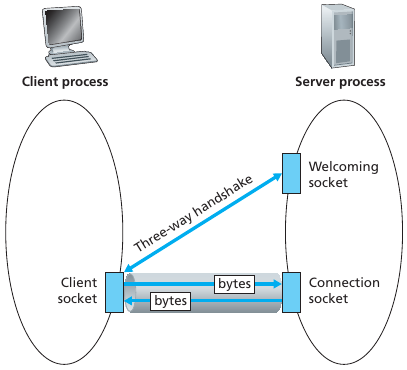

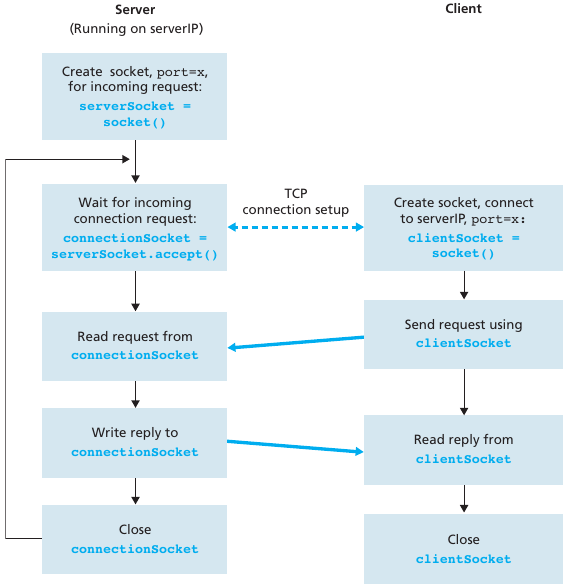

TCP socket:

API:

TCP socket identified by 4-tuple:

demux: receiver uses all four values to direct

segment to appropriate socket.

Server host may support many simultaneous TCP sockets:

Each socket is identified by its own 4-tuple.

Web servers have different sockets for each connecting client.

Non-persistent HTTP will have different socket for each request.

UDP looked like this:

TCP looks like this (e.g., Web server and two clients):

Connection-orientation:

Transmission Control Protocol is a connection-oriented protocol.

This means that it requires handshaking to set up end-to-end

communications.

Once a TCP connection is made via a 3-way handshake, an application

sends data simply by writing to that connection.

No further application-level addressing is needed.

TCP connections are managed by the operating-system kernel, not by the

application.

As part of TCP connection establishment, both sides of the connection

will initialize many TCP state variables in memory.

Reliable:

Manages message acknowledgment, re-transmission, and timeout.

Multiple attempts to deliver the message are made.

If part of a message gets lost along the way, the server will re-request

the lost part.

There will be either no missing data, or, in case of multiple timeouts,

a connection is dropped.

TCP numbers each packet, keeps track of which are lost, and re-transmits

them after a timeout.

It holds early-arriving out-of-order packets for delivery in the correct

sequence at a later time.

Every arriving data packet is acknowledged by the receiver.

Timeout and re-transmission occurs when an acknowledgment packet isn’t

received by the sender within a given time.

Ordered data transfer:

If two messages are sent over a connection in sequence, the first

message will reach the receiving application first.

When data segments arrive in the wrong order, TCP buffers delay the

out-of-order data until all data can be properly re-ordered and

delivered to the application.

The destination host re-arranges received packets according to sequence

number

Heavyweight:

TCP requires three packets to set up a socket connection, before any

user data can be sent.

TCP handles reliability and congestion control.

Streaming:

Data is read as a byte stream:

From the perspective of the application, no distinguishing indications

are transmitted to signal message (segment) boundaries.

An application using TCP can write 1 byte at a time, or 100 kB at a

time.

TCP will buffer and/or divide up the data into appropriate sized

packets.

Re-transmission of lost packets:

Any parts of the cumulative stream not acknowledged are

re-transmitted.

Error-free data transfer:

Service guarantees data were transmitted veritably.

Flow control:

Limits the rate that a sender transfers data, to facilitate consistent

delivery.

The receiver continually hints to the sender how much data can be

received.

Controlled by a sliding window parameter.

When the receiving host’s buffer fills, the next acknowledgment contains

a 0 in the window size, to stop transfer and allow the data in the

buffer to be processed.

Thus, sender will not overwhelm receiver’s buffers.

Congestion control:

Self-throttles to fairly utilize bandwidth between all connections.

Point-to-point:

Always between a single sender and a single receiver (not multiple).

Full duplex

Once a connection is set up, user data may be sent bi-directionally over

the connection.

If there is a TCP connection between Process A on one host and Process B

on another host, then application-layer data can flow from Process A to

Process B at the same time as application-layer data flows from Process

B to Process A.

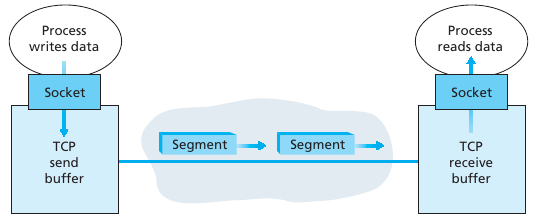

TCP connection consists of both:

buffers, variables, and a socket connection to a process in one host,

and

another set of buffers, variables, and a socket connection to a process

in another host.

No buffers or variables are allocated to the connection in the network

elements (routers, switches, and repeaters) between the hosts.

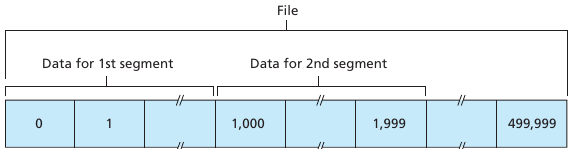

TCP directs data to the connection’s send buffer, which is one of the

buffers that is set aside during the initial three-way handshake.

From time to time, OS’s TCP core will grab chunks of data from the send

buffer and pass the data to the network layer.

The maximum amount of data that can be grabbed and placed in a segment

is limited by the maximum segment size (MSS).

The MSS is typically set by first determining the length of the largest

link-layer frame that can be sent by the local sending host (the

so-called maximum transmission unit, MTU), and then setting the MSS to

ensure that a TCP segment (when encapsulated in an IP datagram) plus the

TCP/IP header length (typically 40 bytes) will fit into a single

link-layer frame.

TCP pairs each chunk of client data with a TCP header, thereby forming

TCP segments.

The segments are passed down to the network layer, where they are

separately encapsulated within network-layer IP datagrams.

The IP datagrams are then sent into the network.

When TCP receives a segment at the other end, the segment’s data is

placed in the TCP connection’s receive buffer.

+++++++++++++++++++++++ Cahoot-03-3

What identifies a TCP stream?

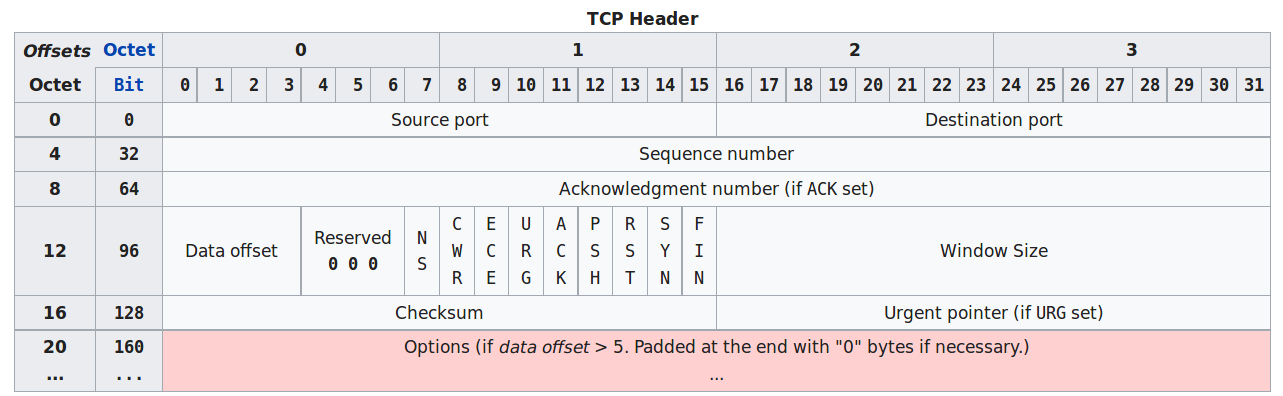

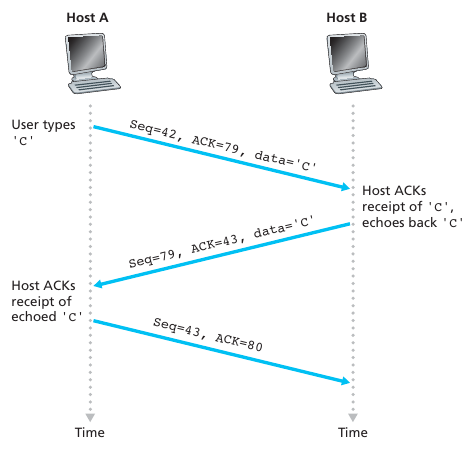

Sequence number (32 bits), acknowledgment number (32 bits),

and window (16 bits)

Used to provide a reliable data transfer, using a window-based

protocol.

In a TCP bytestream, each byte of the stream consumes one sequence

number.

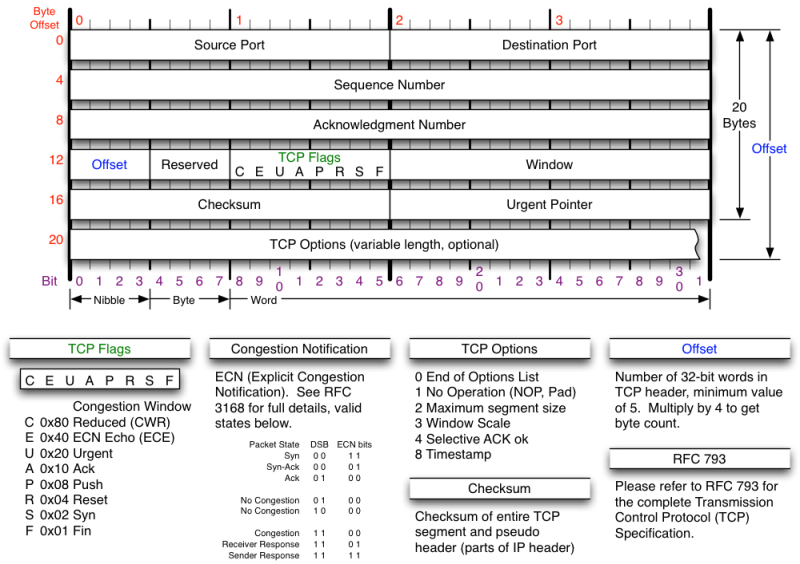

Segment structure details (also observe this is Wireshark, and

compare side-by-side):

Source port (16 bits)

Identifies the sending port.

Destination port (16 bits)

Identifies the receiving port.

Sequence number (32 bits)

For reliability.

Has a dual role:

If the SYN flag is set (1), then this is the initial sequence

number.

The sequence number of the actual first data byte and the acknowledged

number in the corresponding ACK are then this sequence number plus

1.

If the SYN flag is clear (0), then this is the accumulated sequence

number of the first data byte of this segment for the current

session.

Acknowledgment number (32 bits)

For reliability.

If the ACK flag is set then the value of this field is the next sequence

number that the sender of the ACK is expecting.

This acknowledges receipt of all prior bytes (if any).

The first ACK sent by each end acknowledges the other end’s initial

sequence number itself, but no data.

Data offset (4 bits)

Specifies the size of the TCP header in 32-bit words.

The minimum size header is 5 words and the maximum is 15 words thus

giving the minimum size of 20 bytes and maximum of 60 bytes, allowing

for up to 40 bytes of options in the header.

This field gets its name from the fact that it is also the offset from

the start of the TCP segment to the actual data.

Reserved (3 bits)

For future use and should be set to zero.

Flags (9 bits) (aka Control bits)

Window size (16 bits)

For flow control.

The size of the receive window, which specifies the number of window

size units (by default, bytes) (beyond the segment identified by the

sequence number in the acknowledgment field) that the sender of this

segment is currently willing to receive (see Flow control and Window

Scaling).

Checksum (16 bits)

The 16-bit checksum field is used for error-checking of the header, the

Payload, and a Pseudo-Header.

The Pseudo-Header consists of the Source IP Address, the Destination IP

Address, the protocol number for the TCP-Protocol (0x0006), and the

length of the TCP-Headers including Payload (in Bytes).

Urgent pointer (16 bits)

If the URG flag is set, then this 16-bit field is an offset from the

sequence number indicating the last urgent data byte.

Options (Variable 0320 bits, divisible by 32)

* The length of this field is determined by the data offset field.

Options have up to three fields: Option-Kind (1 byte), Option-Length (1

byte), Option-Data (variable). The Option-Kind field indicates the type

of option, and is the only field that is not optional. Depending on what

kind of option we are dealing with, the next two fields may be set: the

Option-Length field indicates the total length of the option, and the

Option-Data field contains the value of the option, if applicable. For

example, an Option-Kind byte of 0x01 indicates that this is a No-Op

option used only for padding, and does not have an Option-Length or

Option-Data byte following it. An Option-Kind byte of 0 is the End Of

Options option, and is also only one byte. An Option-Kind byte of 0x02

indicates that this is the Maximum Segment Size option, and will be

followed by a byte specifying the length of the MSS field (should be

0x04). This length is the total length of the given options field,

including Option-Kind and Option-Length bytes. So while the MSS value is

typically expressed in two bytes, the length of the field will be 4

bytes (+2 bytes of kind and length). In short, an MSS option field with

a value of 0x05B4 will show up as (0x02 0x04 0x05B4) in the TCP options

section. Some options may only be sent when SYN is set; they are

indicated below as [SYN]. Option-Kind and standard lengths given as

(Option-Kind,Option-Length).

* 0 (8 bits): End of options list

* 1 (8 bits): No operation (NOP, Padding) This may be used to align

option fields on 32-bit boundaries for better performance.

* 2,4,SS (32 bits): Maximum segment size (see maximum segment size)

[SYN]

* 3,3,S (24 bits): Window scale (see window scaling for details)

[SYN][10]

* 4,2 (16 bits): Selective Acknowledgment permitted. [SYN] (See

selective acknowledgments for details)[11]

* 5,N,BBBB,EEEE,… (variable bits, N is either 10, 18, 26, or 34)-

Selective Acknowledgment (SACK)[12] These first two bytes are followed

by a list of 14 blocks being selectively acknowledged, specified as

32-bit begin/end pointers.

* 8,10,TTTT,EEEE (80 bits)- Timestamp and echo of previous timestamp

(see TCP timestamps for details)

* The remaining options are historical, obsolete, experimental, not yet

standardized, or unassigned. Option number assignments are maintained by

the IANA.

Padding

The TCP header padding is used to ensure that the TCP header ends, and

data begins, on a 32 bit boundary. The padding is composed of zeros.

The robustness principle (good advice in networking and in life…):

The handling of the TCP options by TCP implementations is one of the many applications of the robustness principle, which is usually attributed to Jon Postel, and is often quoted as:

“Be liberal in what you accept, and conservative in what you send” RFC 1122

In other words:

Even when you have the capacity to understand complexity and variety,

speak simply.

Can you accurately explain a complex topic to someone who does not have

a full mastery your native language?

The robustness principle implies that a TCP implementation should be

able to accept TCP options that it does not understand, and that it

should be able to parse any received segment without crashing, even if

the segment contains an unknown TCP option.

These options come in initially received SYN segments.

Options that have not been proposed by the client in the SYN segment, a

server should not send in the SYN+ACK segment or later segments.

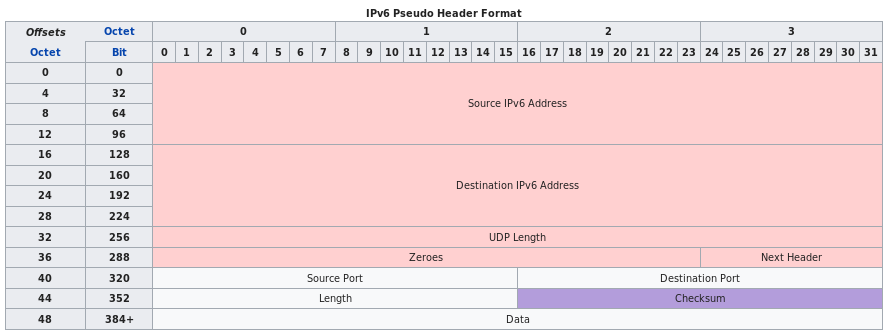

TCP checksum also has extra IP information added:

Minor layering mix-up.

TCP and IP were not independent layers long ago (TCP/IP).

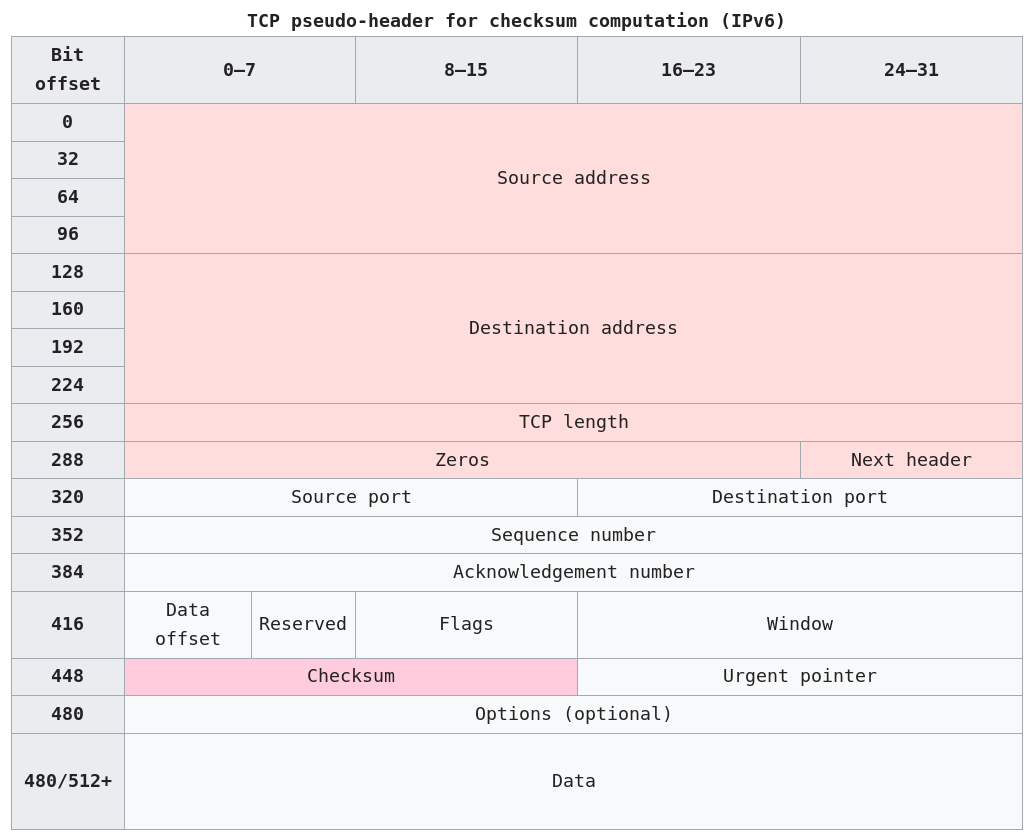

The method used to compute the checksum is changed, as per RFC

2460:

Any transport or other upper-layer protocol that includes the addresses

from the IP header in its checksum computation must be modified for use

over IPv6, to include the 128-bit IPv6 addresses instead of 32-bit IPv4

addresses.

Source address:

The one in the IPv6 header.

Destination address:

The final destination.

If the IPv6 packet doesn’t contain a Routing header, TCP uses the

destination address in the IPv6 header.

Otherwise, at the originating node, it uses the address in the last

element of the Routing header, and, at the receiving node, it uses the

destination address in the IPv6 header.

TCP length:

The length of the TCP header and data.

Next Header:

The protocol value for TCP (6).

More to come below (protocol operation).

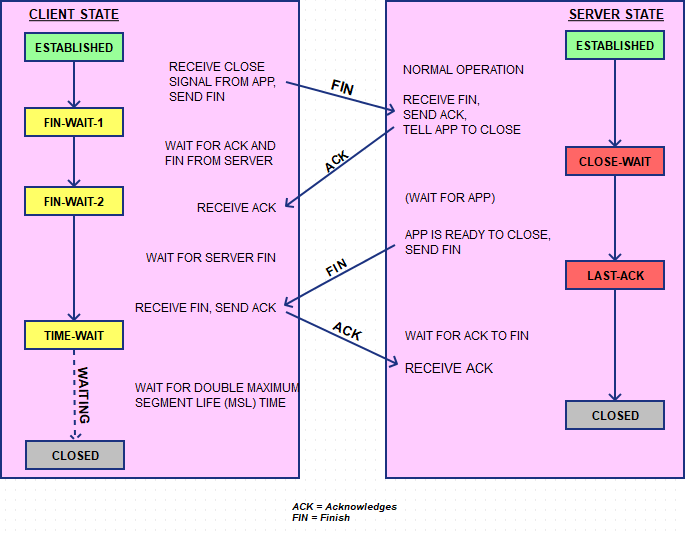

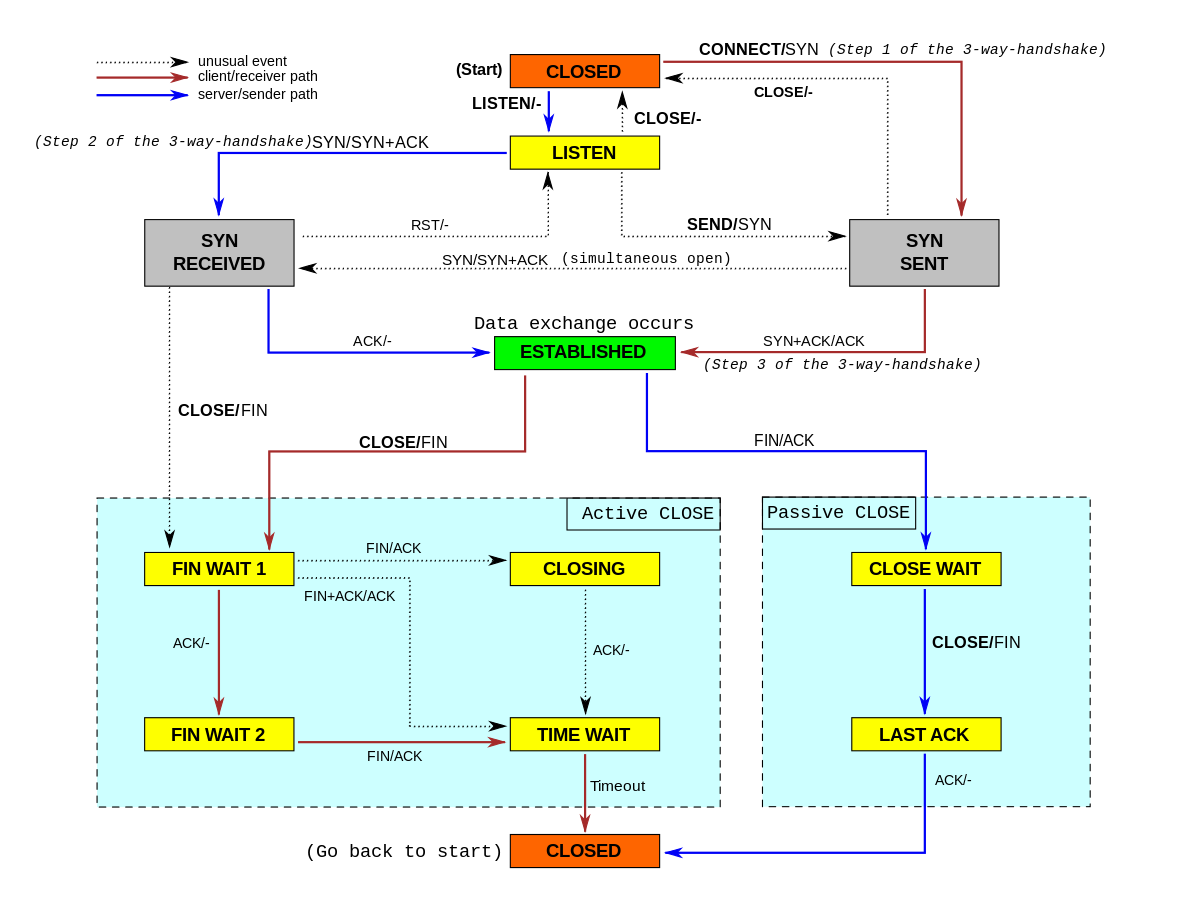

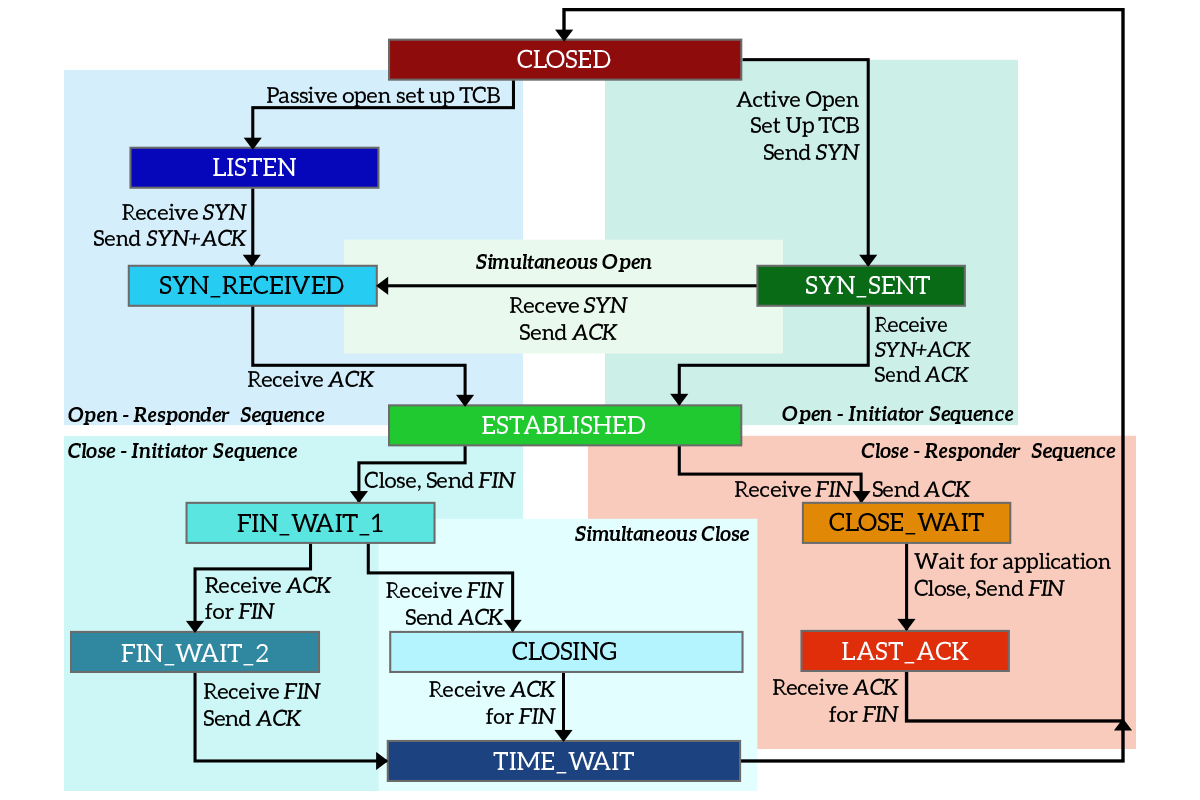

TCP protocol operations may be divided into three phases.

1. Connections must be properly established in a multi-step handshake

process (connection establishment)

2. before entering the data transfer phase.

3. After data transmission is completed, the connection termination

closes established virtual circuits and releases all allocated

resources.

Trace visiting:

*_socket_TCP*.py in wiresharkFollow protocol, lest your rock climbing partner falls to their

death…

Climber: “On belay?” (Are you ready to belay me?)

Belayer: “Belay on.” (Slack is gone and I’m ready.)

Climber: “Climbing.” (I’m going to climb now.)

Belayer: “Climb on.” (I’m ready for you to climb.)

Show below in Wireshark, with relative and real sequence numbers; compare side-by-side.

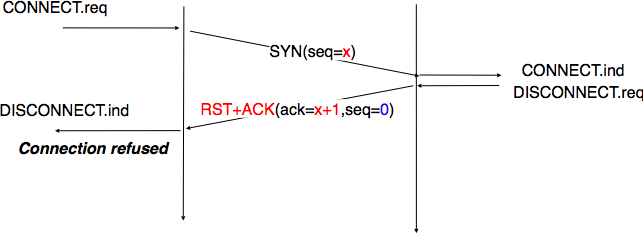

First, if the server is NOT accepting

connections:

Will be relevant later (nmap uses this).

Second, if the server IS accepting

connections:

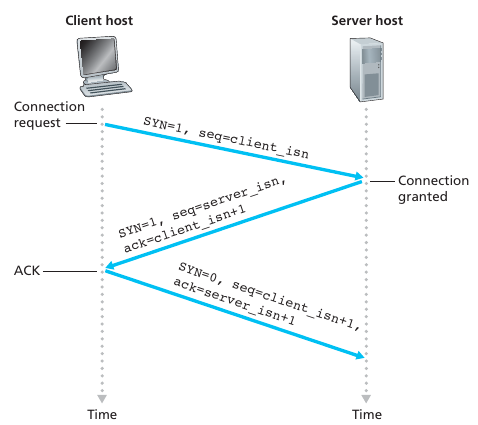

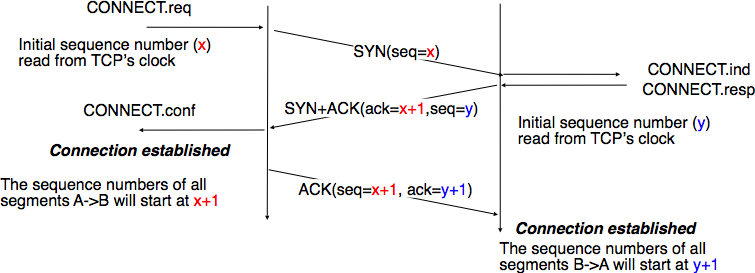

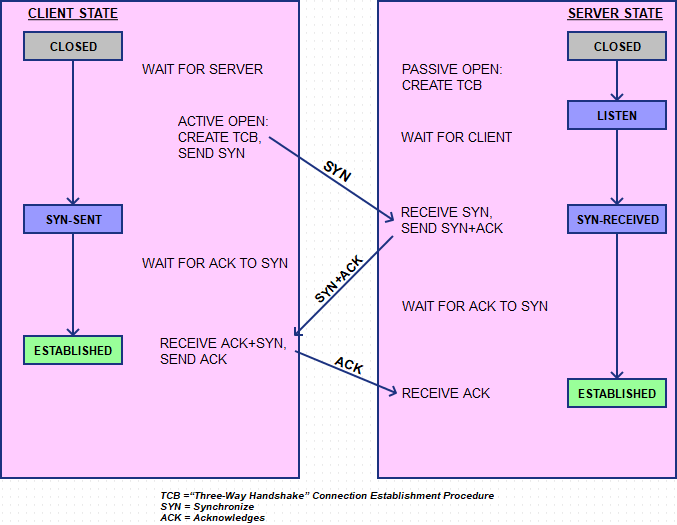

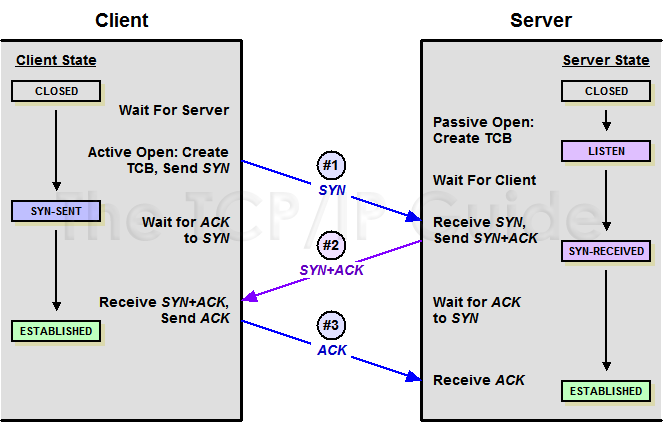

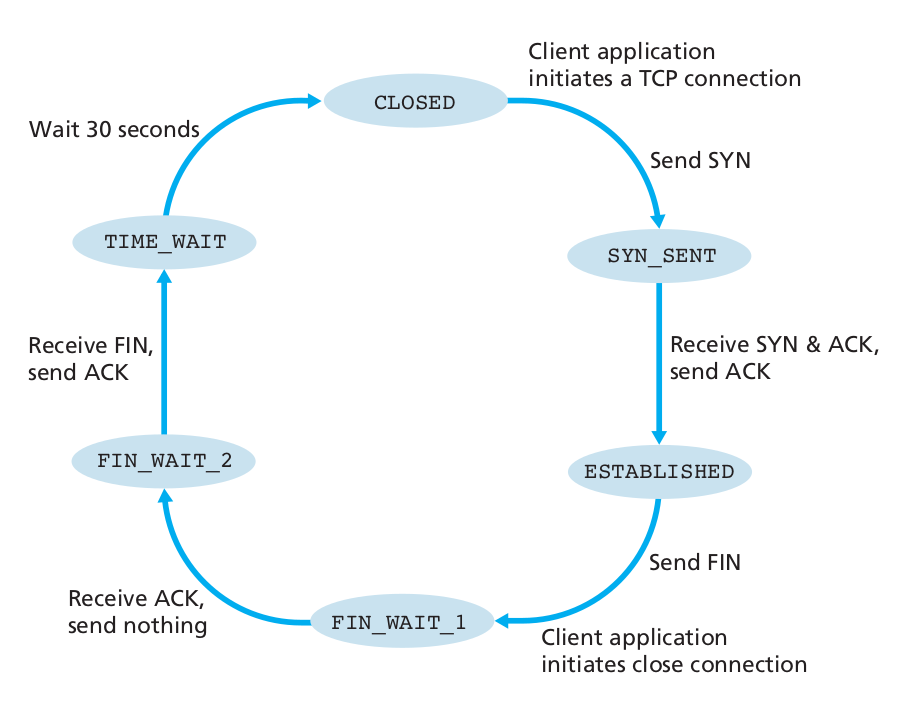

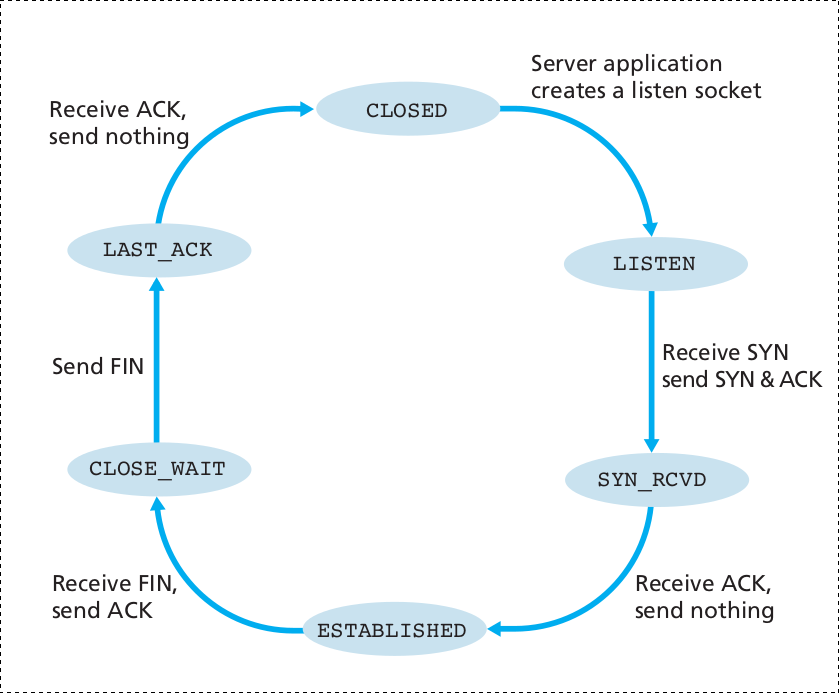

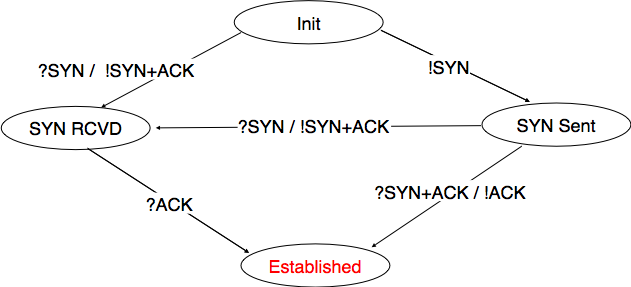

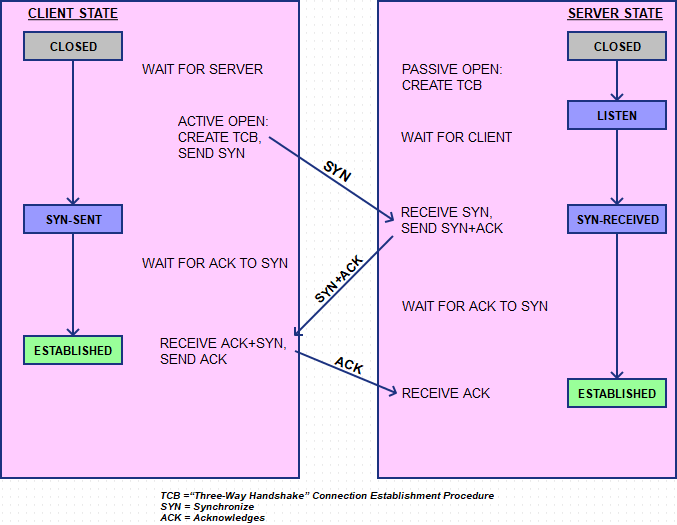

To establish a connection, TCP uses a three-way handshake.

Before a client attempts to connect with a server, the server must first

bind to and listen at a port to open it up for connections: this is

called a passive open.

Once the passive open is established, a client may initiate an active

open.

To establish a connection, the three-way (or 3-step) handshake

occurs:

At this point, both the client and server have received an

acknowledgment of the connection.

The steps 1, 2 establish the connection parameter (sequence number) for

one direction and it is acknowledged.

The steps 2, 3 establish the connection parameter (sequence number) for

the other direction and it is acknowledged.

With these, a full-duplex communication is established.

Step 1. syn

Step 2. synack

The connection-granted segment is referred to as a SYNACK segment.

Step 3. ack

Once these three steps have been completed, the client and server hosts can send segments containing data to each other.

In each of these future segments, the SYN bit will be set to zero.

Note that in order to establish the connection, three packets are sent between the two hosts

In full detail:

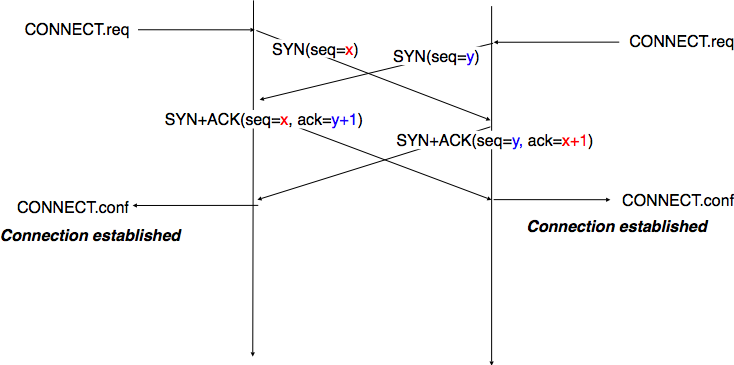

Simultaneous establishment of a TCP connection (rare, weird)

Show this in Wireshark, with relative and real sequence numbers; compare side-by-side.

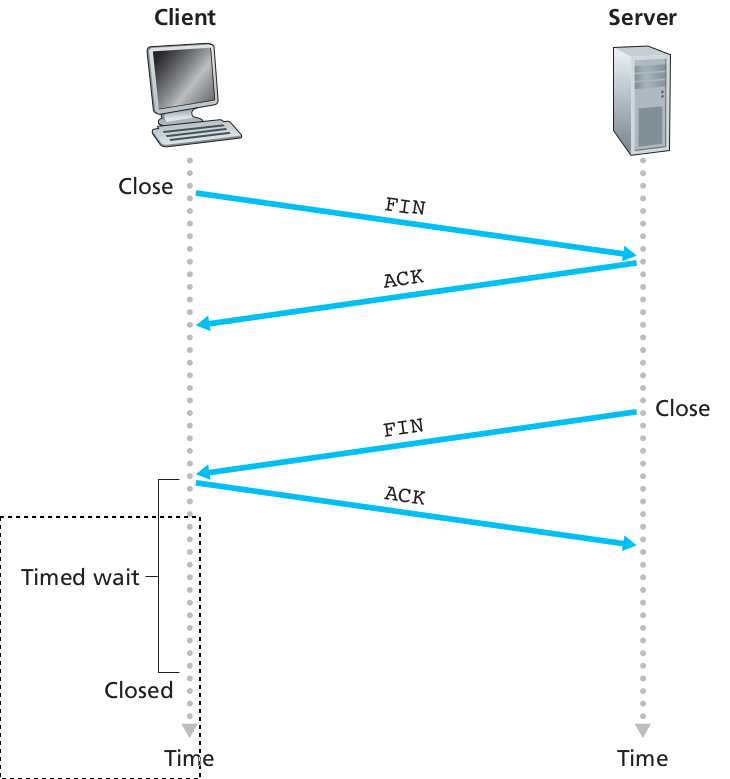

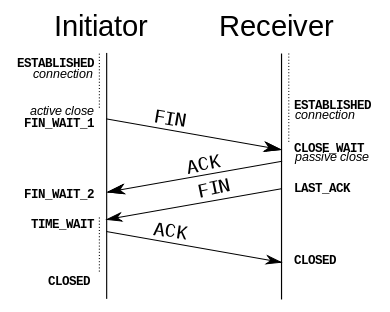

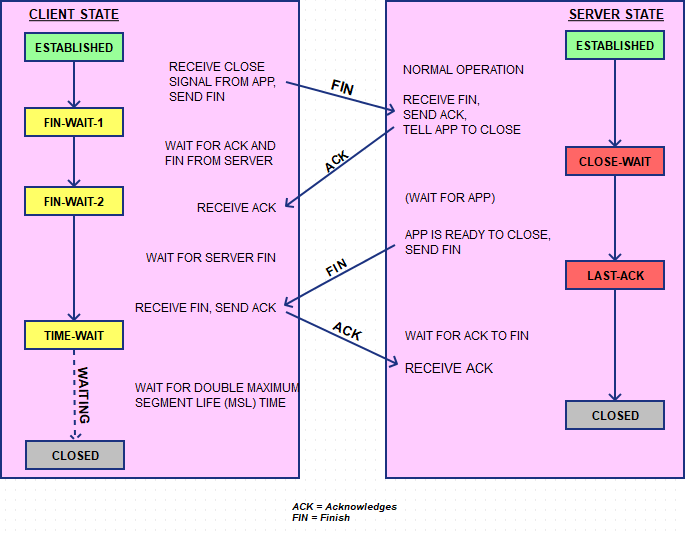

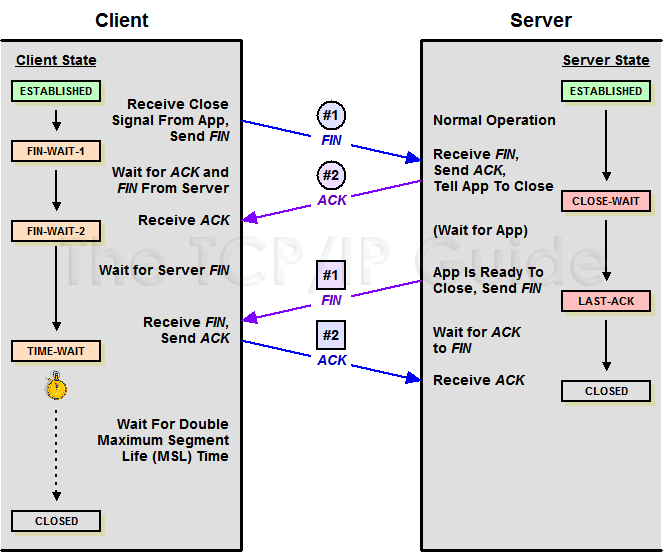

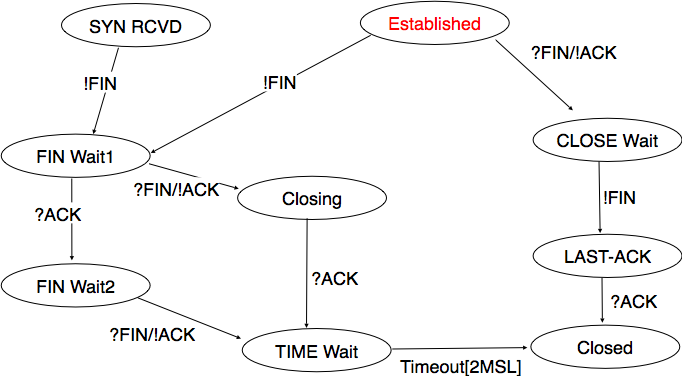

When a connection ends, the “resources” (that is, the buffers and variables) in the hosts are de-allocated.

A’s FIN is, in effect, a promise to B not to send any more.

However, A must still be prepared to receive data from B, hence the

optional data shown in the diagram.

A good example of this occurs when A is sending a stream of data to B to

be sorted.

A sends FIN to indicate that it is done sending, and only then does B

sort the data and begin sending it back to A. This can be generated with

the command, on A:

$cat thefile | ssh B sort.

That said, the presence of the optional B-to-A data above following A’s

FIN is relatively less common.

In the diagram above, A sends a FIN to B and receives an ACK, and then,

later, B sends a FIN to A and receives an ACK.

This essentially amounts to two separate two-way closure handshakes.

In the absence of the optional data from B to A after A sends its

FIN, the closing sequence reduces to the left-hand diagram below:

Relative:

| Num | A sends | B sends |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | SYN, seq=0 | |

| 2 | SYN+ACK, seq=0, ack=1 (expecting) | |

| 3 | ACK, seq=1, ack=1 (ACK of SYN) | |

| 4 | “abc”, seq=1, ack=1 | |

| 5 | ACK, seq=1, ack=4 | |

| 6 | “defg”, seq=4, ack=1 | |

| 7 | seq=1, ack=8 | |

| 8 | “foobar”, seq=8, ack=1 | |

| 9 | seq=1, ack=14, “hello” | |

| 10 | seq=14, ack=6, “goodbye” | |

| 11,12 | seq=21, ack=6, FIN | seq=6, ack=21 ;; ACK of “goodbye”, crossing packets |

| 13 | seq=6, ack=22 ;; ACK of FIN | |

| 14 | seq=6, ack=22, FIN | |

| 15 | seq=22, ack=7 ;; ACK of FIN |

Recall: these sequence numbers are actually big

numbers, that differ relatively by the amounts above (and as displayed

in Wireshark).

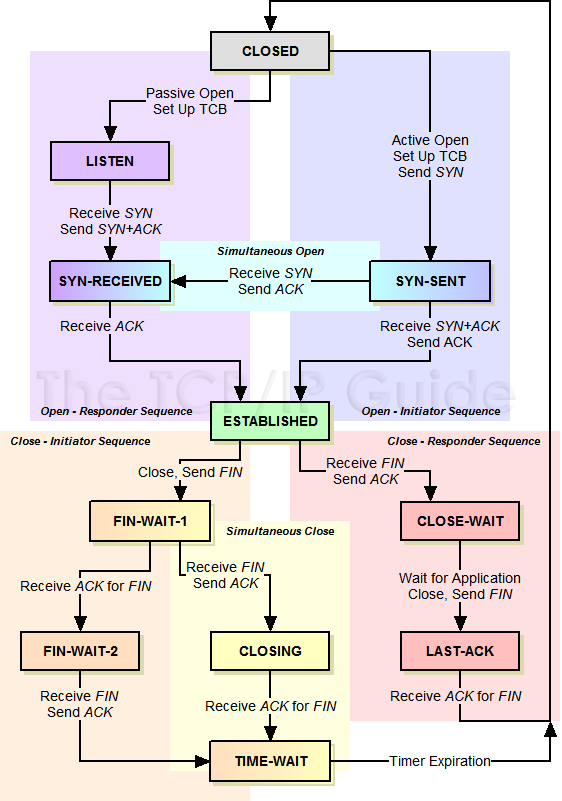

During the lifetime of a TCP connection, the local end-point undergoes a series of state changes:

++++++++++++++++++++ Cahoot-03-4

Trace Wireshark

Download this:

http://gaia.cs.umass.edu/wireshark-labs/alice.txt

Upload this:

http://gaia.cs.umass.edu/wireshark-labs/TCP-wireshark-file1.html

Starting from the Established state, there are two main paths through the below FSM.

Both establishment and termination:

For more detail, see:

http://www.medianet.kent.edu/techreports/TR2005-07-22-tcp-EFSM.pdf

This is what is kept associated with the “table” of all current streams, in RAM, for both the client and the server:

Most implementations allocate an entry in a table that maps a session

to a running operating system process.

Because TCP packets do not include a session identifier, both endpoints

identify the session using the client’s address and port.

Whenever a packet is received, the TCP implementation must perform a

lookup on this table to find the destination process.

Each entry in the table is known as a Transmission Control

Block or TCB.

It contains information about the endpoints (IP and port), status of the

connection, running data about the packets that are being exchanged and

buffers for sending and receiving data.

The number of sessions in the server side is limited only by memory and

can grow as new connections arrive, but the client must allocate a

random port before sending the first SYN to the server.

This port remains allocated during the whole conversation, and

effectively limits the number of outgoing connections from each of the

client’s IP addresses.

If an application fails to properly close non-required connections, a

client can run out of resources and become unable to establish new TCP

connections, even from other applications.

Both endpoints must also allocate space for unacknowledged packets and

received (but unread) data.

+++++++++++++++++++++ Cahoot-03-5

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Port_scanner

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nmap

Our discussion above has assumed that both the client and server are

prepared to communicate,

i.e., that the server is listening on the port to which the client sends

its SYN segment.

What if a host receives a mis-matched TCP segment,

whose port numbers or source IP address do not match any existing

sockets in the host?

For example, suppose a host receives a TCP SYN packet with destination

port 80,

but the host is not accepting connections on port 80

(that is, it is not running a Web server on port 80).

Then the host will send a special reset segment to the source.

This TCP segment has the RST flag bit set to 1.

Thus, when a host sends a reset segment, it is telling the source:

“I don’t have a socket for that segment. Please do not resend the

segment.”

When a host receives a UDP packet whose destination port number doesn’t

match with an ongoing UDP socket,

the host often sends a special ICMP datagram.

Now that we have a good understanding of TCP connection

management,

let’s revisit the nmap port-scanning tool and examine more closely how

it works.

To explore a specific TCP port, say port 6789, on a target

host,

nmap will send a TCP SYN segment with destination port 6789 to that

host.

There are three possible outcomes:

The source host receives a TCP SYNACK segment from the target host. Since this means that an application is running with TCP port 6789 on the target post, nmap returns “open.”

The source host receives a TCP RST segment from the target host. This means that the SYN segment reached the target host, but the target host is not running an appli- cation with TCP port 6789. But the attacker at least knows that the segments destined to the host at port 6789 are not blocked by any firewall on the path between source and target hosts. (Firewalls are discussed in Chapter 8.)

The source receives nothing. This likely means that the SYN segment was blocked by an intervening firewall and never reached the target host.

Nmap is a powerful tool, which can “case the joint” not only for open

TCP ports, but also for open UDP ports, for firewalls and their

configurations, and even for the versions of applications and operating

systems.

Much of this is done by manipulating TCP connection-management or other

administrative segments, for example:

syn scan, ack scan, fin scan, window scan

Recall:

Green box above in TCP’s FSM.

For actual data-containing packets, a complex set of protocol details exist.

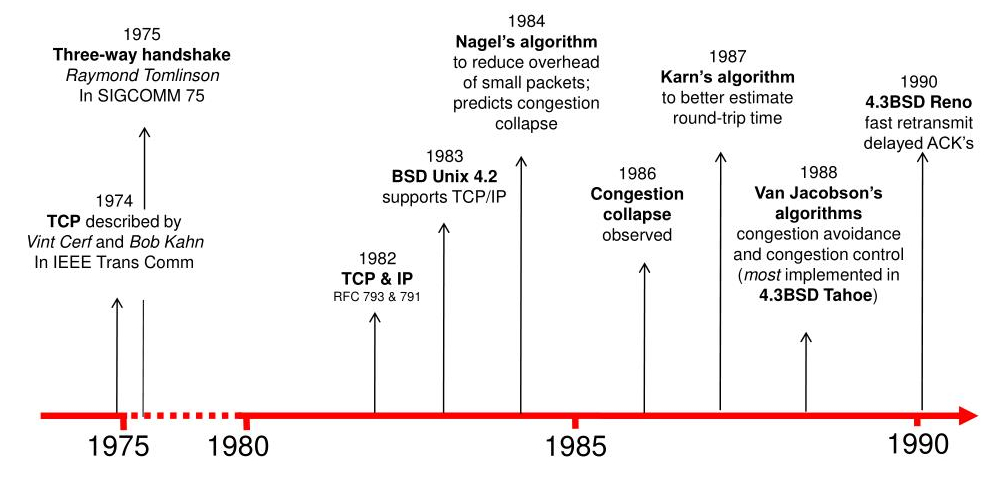

The first designs did not have all the features we’re covering,

which were slowly added over time:

Now, there are many variations on TCP:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TCP_congestion_control#Algorithms

Maximizing transfer - sending many packets

optimistically and rapidly

Reliability and ordered transfer - whole packet

loss

Error detection - corrupt packets

Flow control - don’t overwhelm the receiver

Congestion control - dealing with queues and full

pipes

Stop and wait versus pipe-lining

Pipelining requires that we think about pipelined acknowledgments and

pipelined reliability.

Receive window:

Computer-Networking

https://www.computer-networking.info/1st/html/transport/principles.html

https://www.computer-networking.info/2nd/html/principles/reliability.html

IntroNetworks

http://intronetworks.cs.luc.edu/current2/uhtml/slidingwindows.html

Reliability defines protocols for whole packet loss.

Reliability is not defined as dealing with corrupted packets,

which is handled by error detection below.

Two mechanisms for detecting lost packets:

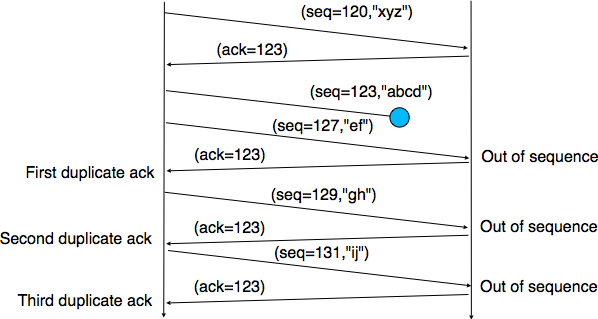

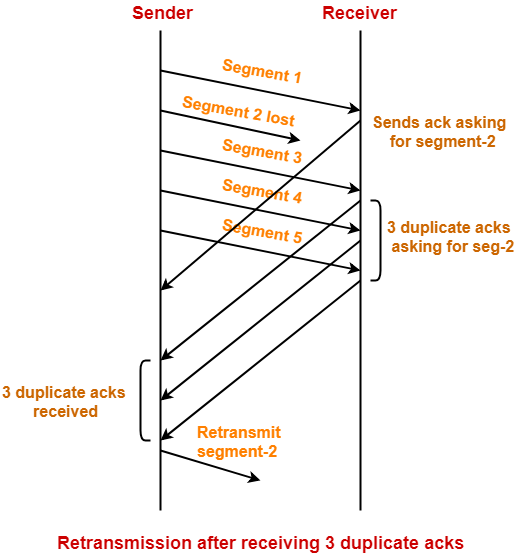

1. Duplicate acknowledgment based re-transmission (dup-ack)

2. Timeout based re-transmission

Reminder: Sequence and acknowledgment numbers

Recall:

TCP Acknowledgments are cumulative and

positive.

We only acknowledge the last received packet,

of a continuous cumulative chain of packets from the

start.

Make sure you get this point before continuing!

Duplicate acknowledgment based re-transmission

(dup-ack):

If a single packet (say packet 127) in a stream is lost,

then the receiver cannot acknowledge packets above 127 because it uses

cumulative ACKs.

Hence the receiver acknowledges packet 123 again on the receipt of

another data packet.

This duplicate acknowledgment is used as a signal for packet loss.

That is, if the sender receives three duplicate acknowledgments,

it re-transmits the last un-acknowledged packet.

A threshold of three is used,

because the network may reorder packets causing duplicate

acknowledgments.

This threshold avoids spurious re-transmissions due to reordering,

though it is still possible.

Indirectly “asking for segment-2”,

is actually just an ack of segment-1:

Question:

When pipelining, if we just lose one packet,

do we have to re-transmit everything,

or just the lost packet?

Sometimes, selective acknowledgments (SACKs) are used,

providing more explicit feedback on which packets have been

received.

This improves TCP’s ability to re-transmit the right packets.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Cahoot-03-6

Timeout based re-transmission

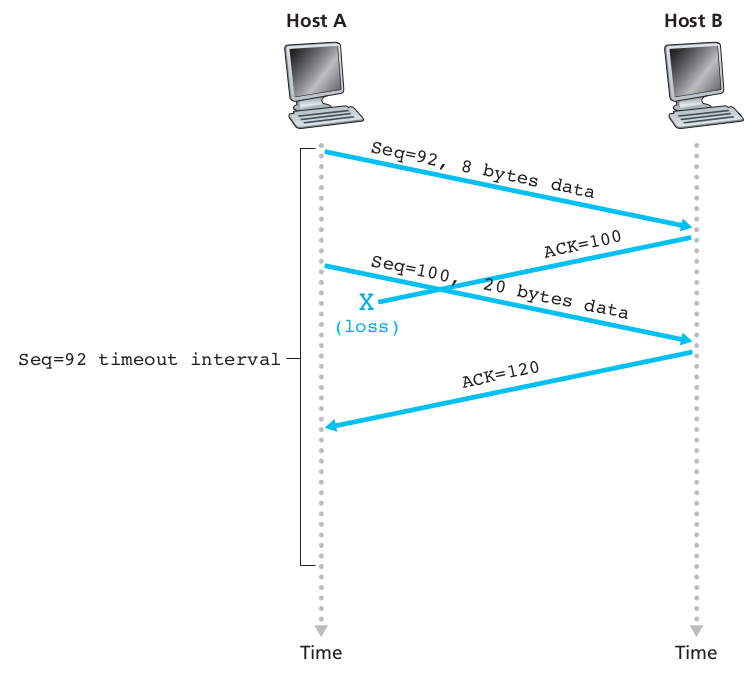

Re-transmission due to a lost acknowledgment:

Cumulative acknowledgment avoids re-transmitting the lost

segment:

Aside/discuss:

What is the definition of control in CS/engineering?

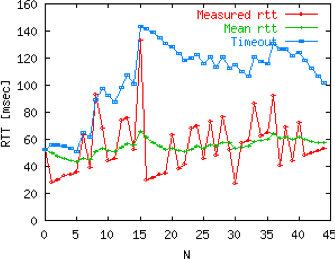

Round Trip Time (RTT) and timeout duration:

First, to decide when a packet has probably been lost,

one needs to know a reasonable timeout threshold.

How do we compute a round-trip time (RTT)?

One good was is an exponential weighted moving average (EWMA).

Whenever a packet is sent, the sender sets a timer.

The timer is set to a conservative prediction of when that packet will

be ack’ed.

If the sender does not receive an ACK by then,

then it transmits that packet again.

The timer is reset every time the sender receives an

acknowledgment.

This means that the re-transmit timer expires only when the sender has

received no acknowledgment for a long time.

Further, in the case a re-transmit timer has expired and no

acknowledgment is received,

the next timer is set to twice the previous value (up to a certain

threshold).

This helps defend against a man-in-the-middle denial of service

attack,

that tries to fool the sender into making so many re-transmissions that

the receiver is overwhelmed.

Summary:

If the sender infers that data has been lost in the network,

using one of the two techniques described above,

then it re-transmits the data.

Such real-time changing of parameters based on the environment creates

momentum,

feedback, and a dynamical distributed process,

especially when interacting with other TCP connections.

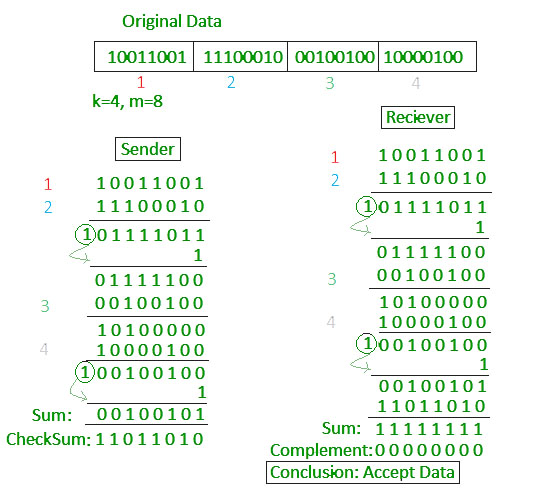

When reviewing the TCP header,

we talked about computing a checksum:

Fold bit-string into 16-bit page, sum bits, invert:

See checksum above, for packet corruption, not loss.

The TCP checksum is a weak check by modern standards

(statistically OK at detecting errors).

Data Link Layers with high bit error rates may require additional link

error correction/detection capabilities.

The weak checksum is partially compensated for by the common use of a

CRC or better integrity check at layer 2,

below both TCP and IP, such as is used in PPP or the Ethernet

frame.

However, this does not mean that the 16-bit TCP checksum is

redundant:

Remarkably, introduction of errors in packets between CRC-protected hops

is common,

but the end-to-end 16-bit TCP checksum catches most of these simple

errors.

This is the end-to-end principle at work.

A concrete example:

Receiver must do the same thing as sender, re-compute,

and compare the value to the checksum the sender sent:

+++++++++++++++++++++ Cahoot-03-7

Broad principles:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flow_control_(data)

As a consequence of pipelining,

we must consider the rate at which we send data,

for our receiver’s ability to process it.

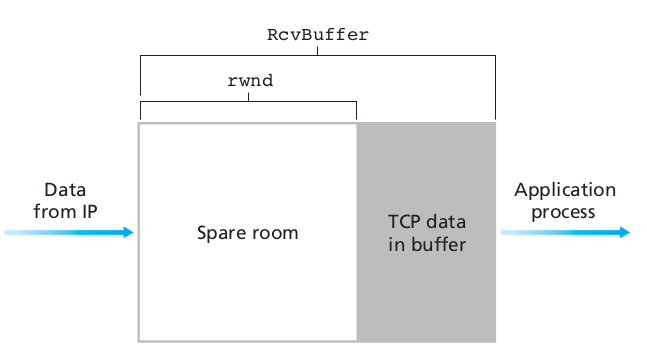

TCP provides flow control by having the sender maintain a variable

called the receive window.

Recall:

Receive window in header above,

receive buffer in TCP block.

The receive window provides the sender an idea of how much free

buffer space is available at the receiver.

Because TCP is full-duplex, the sender at each side of the connection

maintains a distinct receive window.

In each TCP segment, the receiver specifies in the receive

window field.

It defines the amount of additionally received data, in bytes,

that it is willing to buffer for the connection.

The sending host can send only up to that amount of data,

before it must wait for an acknowledgment and window update from the

receiving host.

TCP sequence numbers and receive windows behave very much like a

clock.

The receive window shifts each time the receiver receives and

acknowledges a new segment of data.

Once it runs out of sequence numbers, the sequence number loops back to

0.

The great thing about TCP jokes is that you always get

them.

The problem with TCP jokes is that I’ll keep retelling them slower until

you get them!

As a consequence of pipelining,

we must consider the rate at which we send data,

for our network’s ability to relay it.

A full topic on its own:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TCP_congestion_control

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Additive_increase/multiplicative_decrease

V2

https://www.computer-networking.info/2nd/html/principles/sharing.html#network-congestion

https://www.computer-networking.info/2nd/html/principles/sharing.html#congestion-control

https://www.computer-networking.info/2nd/html/protocols/congestion.html

V1

https://www.computer-networking.info/1st/html/transport/tcp.html#tcp-congestion-control

Intronetworks

http://intronetworks.cs.luc.edu/current2/uhtml/intro.html#congestion

http://intronetworks.cs.luc.edu/current2/uhtml/reno.html

High level idea:

Q: How fast should sender send data, to not overwhelm the network?

A: ??

Q: How do we control the rate of sending data?

A: by controlling:

the number of packets out on the wire, un-acked,

and how rapidly we increase this number over time.

Reminder:

What is the definition of control in CS/engineering?

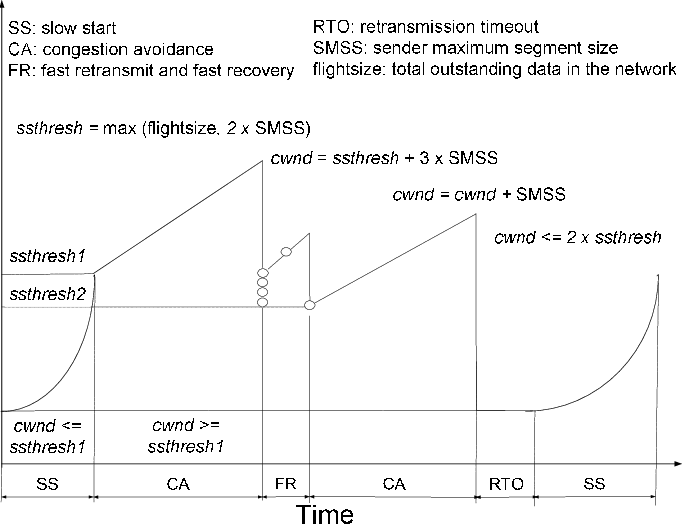

A quick preview (more detail to come):

cwnd is under fine-grained, step-wise contrtol.

ssthresh is a threshold that operates at a courser,

larger, intermittent timescale.

Q: How do we know we’ve overwhelmed the network?

A: by observing:

duplicate acks,

timeouts,

Explicit Congestion Notification (ECN) flag in TCP header (more

rare).

Q: Which indicates worse congestion?

A: A point to ponder, more below.

TCP block data:

cwnd

Fine control of sending rate, modulated to adjust speed.

A congestion window (cwnd) is maintained by the sender.

cwnd is one of the factors that determines the number

of bytes that can be outstanding at any time.

It thus determines the rate at which sender sends data.

This is not to be confused with the sliding window size which is

maintained by the receiver, for the purpose of determining how much data

the receiver’s buffers can handle.

Instead, reducing the congestion window is a means of reducing the

degree to which a link between the sender and the receiver is overloaded

with too much traffic.

It is reduced after observing evidence of congestion.

When a connection is set up, the congestion window, a value maintained

independently at each host, is set to a small multiple of the

MSS allowed on that connection.

ssthresh

A value adjusted only intermittently

It is treated as an occasional set-point for modifying cwnd.

A slow-start threshold (ssthresh) determines how long a ramp-up in speed

occurs.

Both cwnd and ssthresh can be modulated over time, to control sending

rate.

cwnd is fine-grained control.

ssthresh is an occasional resetting threshold.

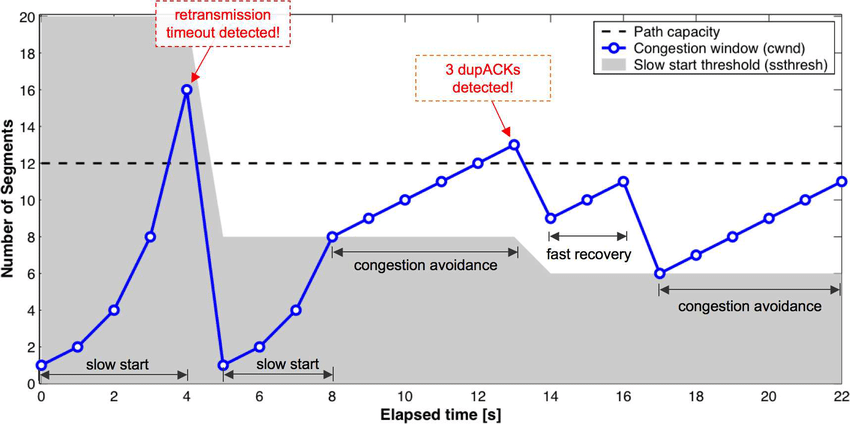

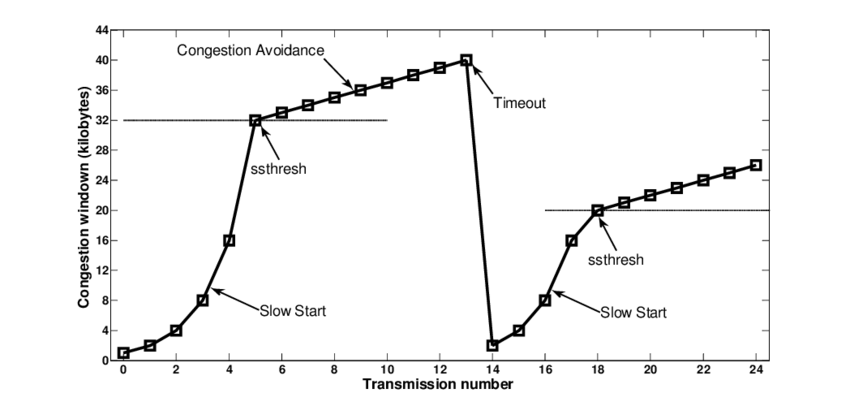

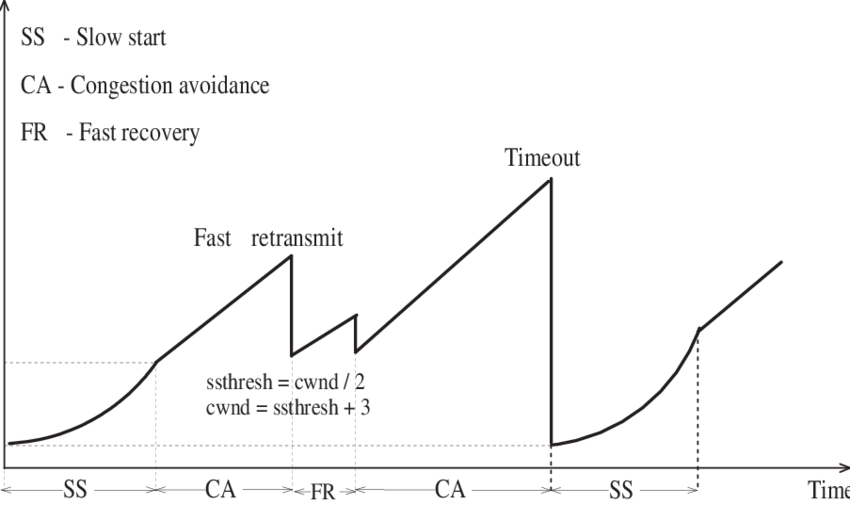

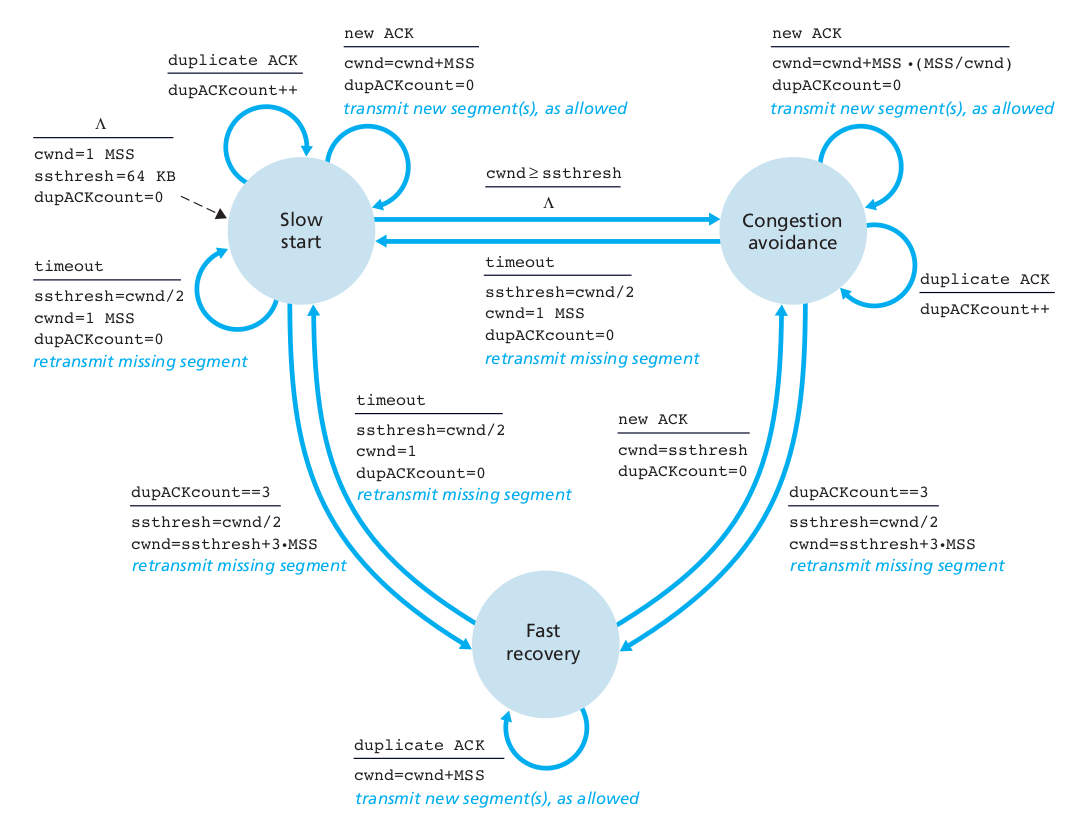

Most modern implementations of TCP contain four intertwined

parts:

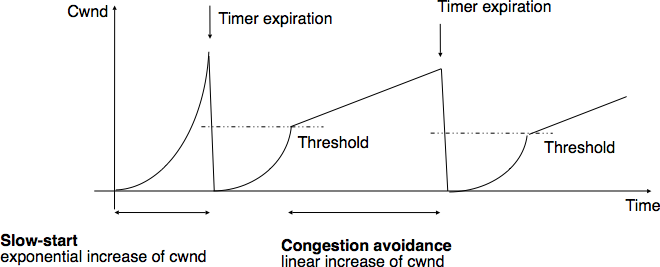

1. slow-start

2. congestion avoidance

3. fast re-transmit (this is just 3xdup-ack)

4. fast recovery (in some versions only, varies)

Overview:

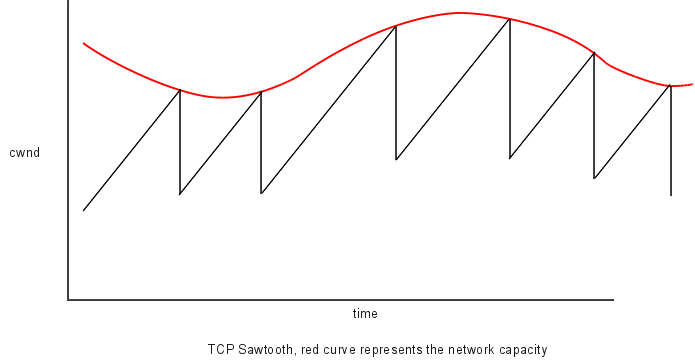

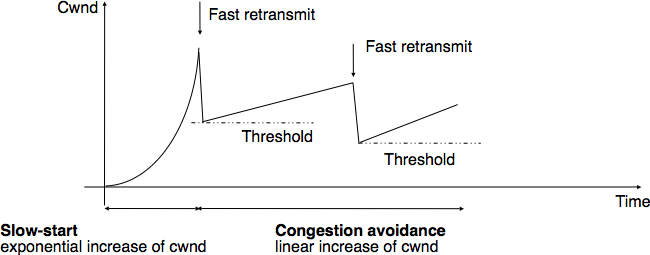

AIMD

Linear growth of cwnd, until a loss, then an exponential

reduction.

Additive increase, multiplicative decrease (AIMD).

Sawtooth is common behavior for a closed-loop control algorithm.

Types of congestion:

Mild congestion (dup-ack)

TCP considers that the network is lightly congested if it receives three

duplicate acknowledgements and performs a fast retransmit.

If the fast retransmit is successful, this implies that only one segment

has been lost.

In this case, TCP performs multiplicative decrease and the congestion

window is divided by 2.

The slow-start threshold is set to the new value of the congestion

window.

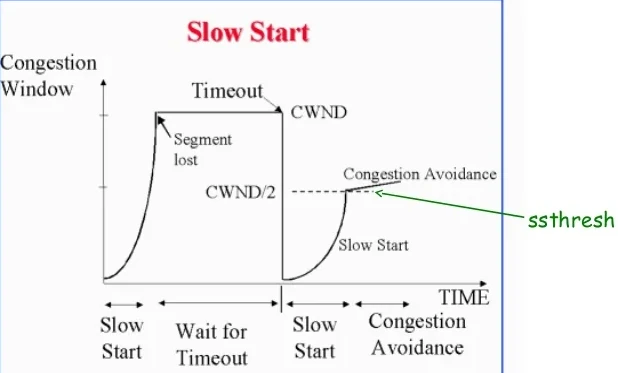

Severe congestion (timeout)

TCP considers that the network is severely congested when its

retransmission timer expires.

In this case, TCP retransmits the first segment, sets the slow-start

threshold to 50% of the congestion window.

The congestion window is reset to its initial value, and TCP performs a

slow-start.

Such behavior could be expressed in pseudocode:

# Initialisation

cwnd = MSS;

ssthresh = swin;

# Ack arrival

if tcp.ack > snd.una: # new ack, no congestion

if cwnd < ssthresh :

# slow-start: increase quickly cwnd

# double cwnd every rtt

cwnd = cwnd + MSS

else:

# congestion avoidance : increase slowly cwnd

# increase cwnd by one mss every rtt

cwnd = cwnd + mss * (mss / cwnd)

else: # duplicate or old ack

if tcp.ack==snd.una: # duplicate acknowledgement

dupacks++

if dupacks==3:

retransmitsegment(snd.una)

ssthresh=max(cwnd / 2, 2 * MSS)

cwnd=ssthresh

else:

dupacks=0

# ack for old segment, ignored

Expiration of the retransmission timer:

send(snd.una) # retransmit first lost segment

sshtresh=max(cwnd / 2, 2 * MSS)

cwnd=MSSThis is a summary of many of the above mechanisms illustrated in FSM

form:

Note: pseudocode and FSM are not the same implementation.

+++++++++++++++++++++ Cahoot-03-8

This is an oddball field in TCP,

which is related to layers below (data-link).

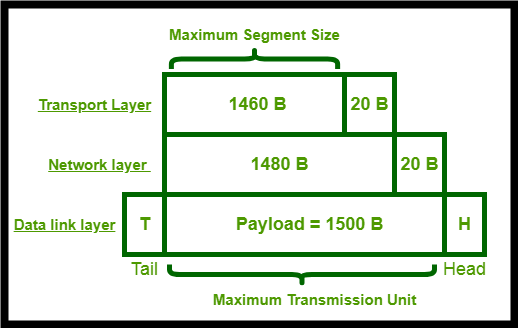

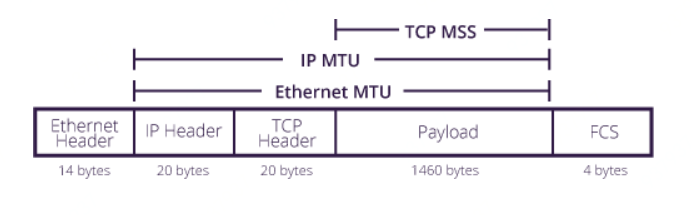

The maximum segment size (MSS) is the largest amount of data, specified

in bytes, that a TCP entity is willing to receive in a single

segment.

Typically the MSS is announced by each side.

MSS announcement is also often called “MSS negotiation”, though that’s a

misnomer.

Two completely independent values of MSS are permitted for the two

directions of data flow in a TCP connection.

Why define a max size at the TCP layer?

IP constraints (one layer down from transport)

IP fragmentation (more later), can lead to packet loss and excessive

re-transmissions.

Thus, to optimize performance, each TCP entitiy’s MSS should be set

small enough.

When the TCP connection is established, MSS announcment uses the MSS

option field.

Why is there IP fragmentation?

Data-link constraints (two layers down from transport)

Each entity is connected to a data-link layer (the next one down).

There are many heterogeneous data-link networks between them.

Each data link layer defines a maximum transmission unit (MTU), above

which, it will not send.

Initialization

The initial MSS value is derived from the maximum transmission unit

(MTU) size of the data link layer network each TCP entitiy is attached

to.

After initialization

Dynamically adjust the MSS.

How?

TCP senders can use path MTU discovery to infer the minimum data-link

layer MTU along the network path between the sender and receiver.

This avoid IP fragmentation within the network.

Less fragmentation reduces loss.

Recall nmap?

Can you hide which ports are open?

Make a secret code to reveal them?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Port_knocking

Attacks:

UDP packets can easily be spoofed for amplification, redirection, or

flooding attacks.

It is easy to send UDP packets with spoofed source IP address.

The attacker sends a small message to a server, with spoofed source

address,

and the server then responds to the spoofed address with a much larger

response message.

This creates a larger volume of traffic to the victim,

than the attacker would be able to generate directly.

Defense:

One approach is for the server to limit the size of its response,

ideally to the size of the client’s request,

until it has been able to verify that the client actually receives the

packets,

sent to its claimed IP address; QUIC uses this approach.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transmission_Control_Protocol#Vulnerabilities

http://seclab.cs.sunysb.edu/sekar/papers/netattacks.pdf

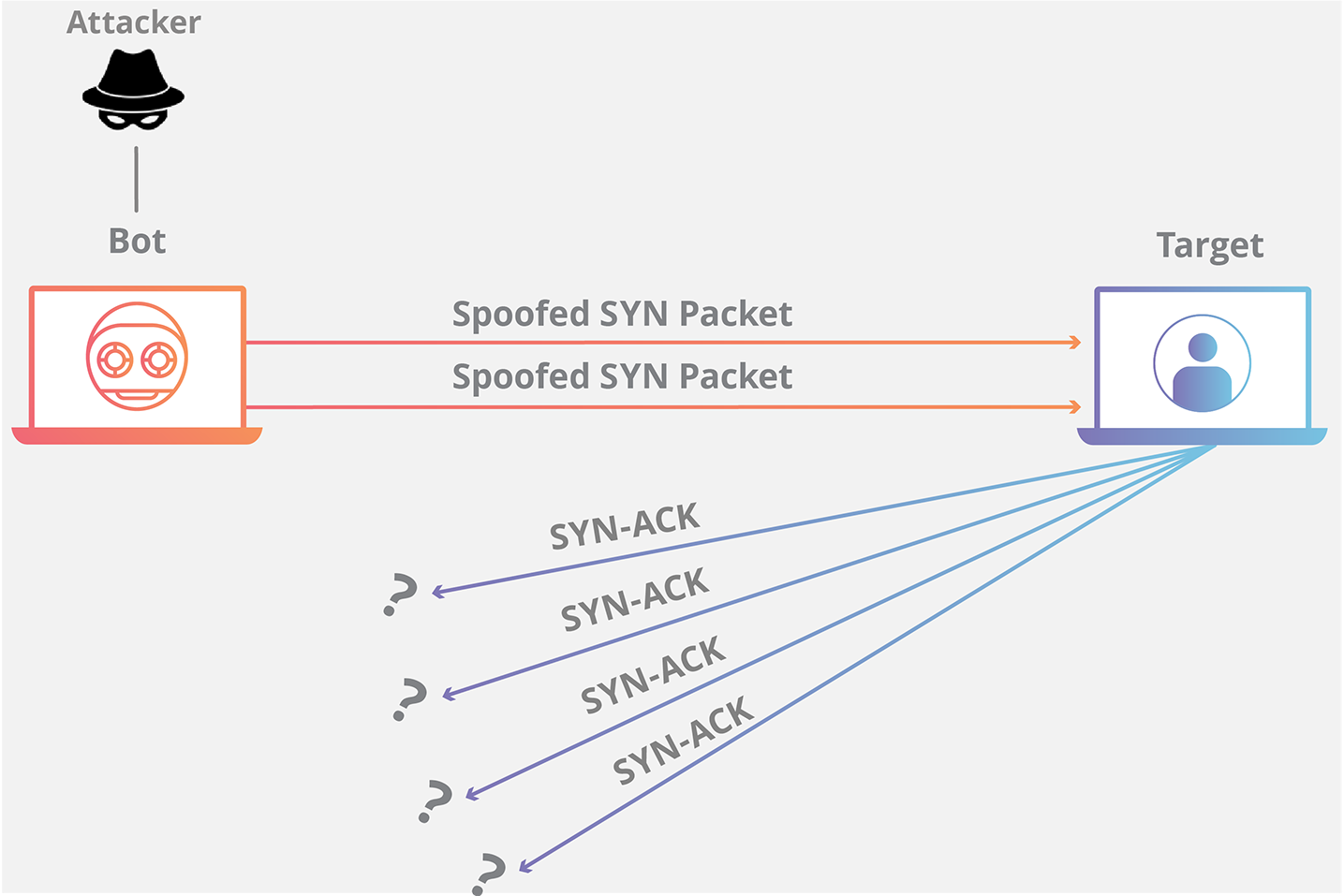

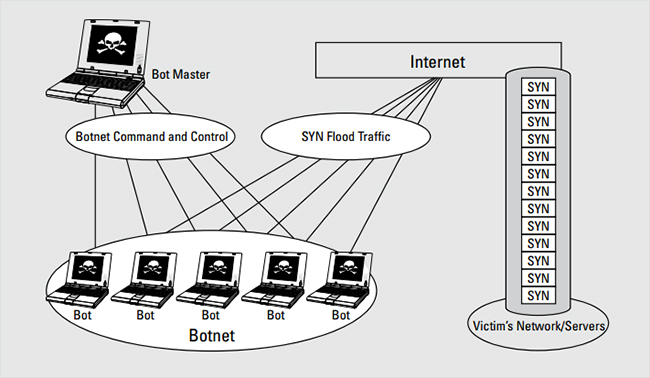

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SYN_flood

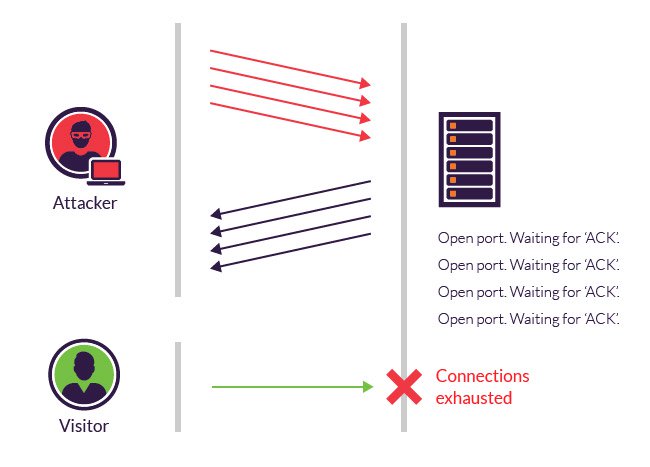

During three-way handshake,

in response to a received SYN,

the server allocates and initializes connection variables and

buffers.

The server then sends a SYNACK in response,

and awaits an ACK segment from the client.

If the client does not send an ACK,

to complete the third step of this 3-way handshake,

eventually, often after a minute or more,

the server will terminate the half-open connection,

and reclaim the allocated resources.

Attacker(s) send a large number of TCP SYN segments,

without completing the third handshake step.

With this deluge of SYN segments,

the server’s connection resources become exhausted,

as they are allocated (but never used!) for half-open connections

Legitimate clients are then denied service.

PUSH and ACK floods are used in other variants of flood attacks.

Some servers attempt to detect syn-floods and fake connections.

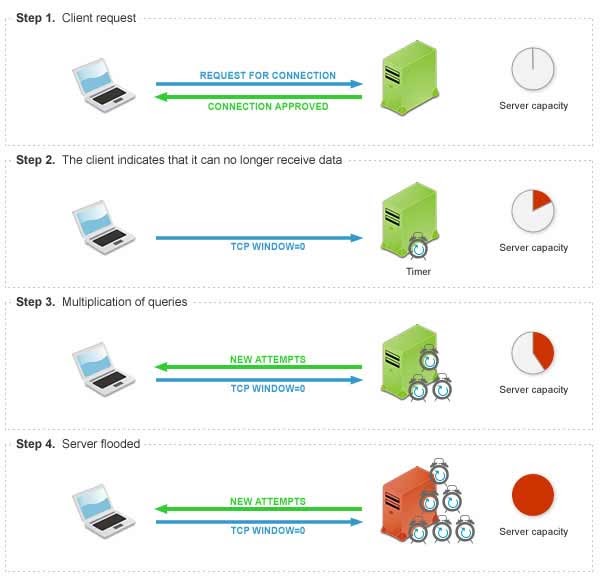

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sockstress

Sockstress is an attack method similar to the floods above.

With a syn flood, the server may time out each attempted

connection.

To avoid this protective defense,

Sockstress provides more convincing evidence of real connection.

Sockstress is a user-land TCP socket stress framework,

that can complete arbitrary numbers of open sockets,

without incurring the typical overhead of tracking state.

Once the socket is established,

it is capable of sending TCP attacks,

that target specific types of kernel and system resources such as:

Counters, Timers, and Memory Pools.

Example, sub-variant:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sockstress#Zero_window_connection_stress

One way to convince the server each connection is real,

increasing timeouts, using a fake connect, and then send window of

0.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TCP_sequence_prediction_attack

Imagine an attacked who is on the same LAN, but is not the gateway

router.

Assuming the attacker does not control the full infrastructure (as an

ISP would),

and thus can not be a perfect MITM,

the attacker wants to send fake packets to a victim.

The attacker hopes to correctly guess the sequence number to be used by

the sending host.

If they can do this, they may be able to send counterfeit packets to the

receiving host.

These packets which will seem to originate from the real sending

host.

The attacker may issue packets using the same source IP address as a

host (spoofed).

By monitoring the traffic before an attack is mounted,

the malicious host can figure out the correct sequence number.

After the IP address and the correct sequence number are known,

it is a race between the attacker and the trusted host to get the

correct packet sent.

The attacker may DoS it’s victim.

Once the attacker has control over the connection,

they are able to send counterfeit packets without getting a

response.

If an attacker can cause delivery of counterfeit packets of this

sort,

they may be able to cause various sorts of mischief, including:

the injection into an existing TCP connection, of data of the attacker’s

choosing,

and the premature closure of an existing TCP connection,

by the injection of counterfeit packets with the RST bit set.

(TCP reset attack).

Note:

A TCP reset attack is easier if attacker is the ISP, why?

An attacker who is able to eavesdrop a TCP session,

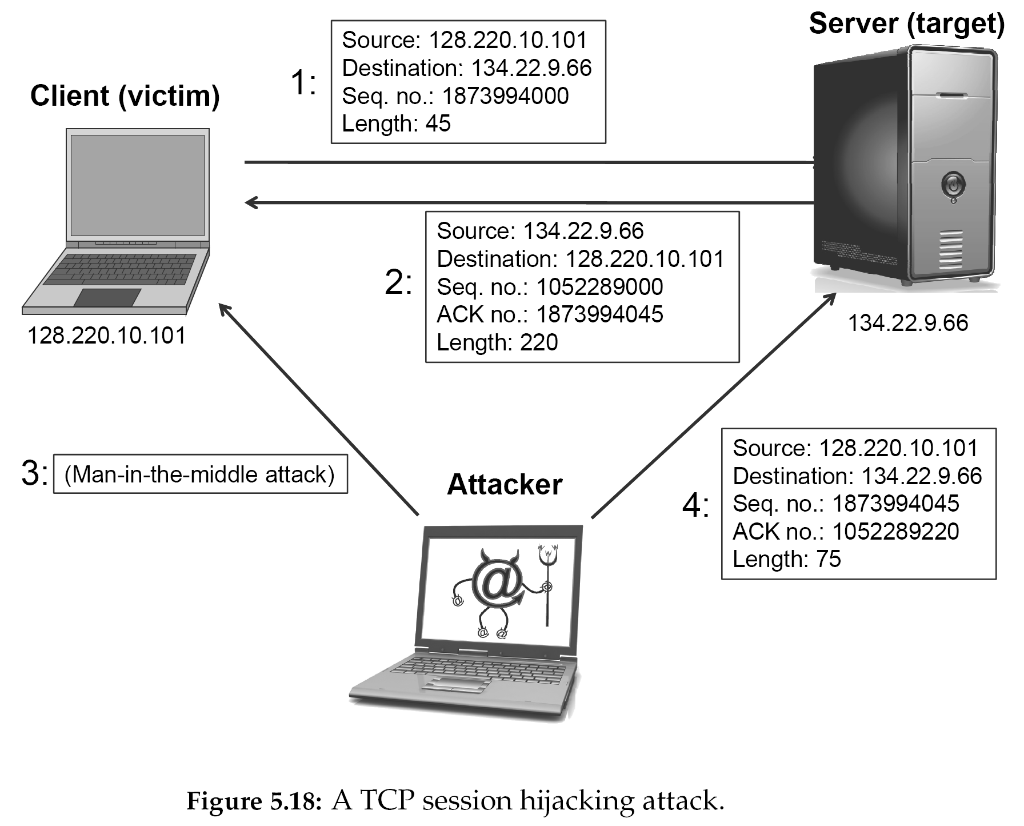

and redirect packets, can hijack a TCP connection.

To do so, the attacker learns the sequence number from the ongoing

communication,

and forges a false segment that looks like the next segment in the

stream.

Such a simple hijack can result in one packet being erroneously accepted

at one end.

When the receiving host acknowledges the extra segment,

to the other side of the connection,

synchronization is lost.

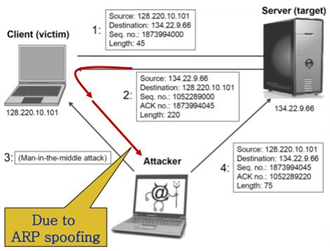

Hijacking might be combined with Address Resolution Protocol (ARP)

spoofing,

or routing attacks that allow taking control of the packet flow,

so as to get permanent control of the hijacked TCP connection.

These are lower level, which we have not covered yet.

Partial fix:

Initial sequence number is now chosen at random.

ARP spoofing (lower layer) we’ll cover latter,

as an extension to this attack.

An attacker who can eavesdrop,

and predict the size of the next packet to be sent,

can cause the receiver to accept a malicious payload,

without disrupting the existing connection.

The attacker injects a malicious packet with the sequence number,

and a payload size of the next expected packet.

When the legitimate packet is ultimately received,

it is found to have the same sequence number and length as a packet

already received,

and is silently dropped as a normal duplicate packet,

and the legitimate packet is “vetoed” by the malicious packet.

Unlike in connection hijacking,

the connection is never de-synchronized,

and communication continues as normal,

after the malicious payload is accepted.

TCP veto gives the attacker less control over the communication,

but makes the attack particularly resistant to detection.

https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6497785

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TCP_reset_attack

In most packets the reset RST bit is set to 0, and has no effect.

However, if the RST bit is set to 1,

then it indicates to the receiving computer that:

the computer should immediately stop using the TCP connection.

Thus, it should not send any more packets,

and discards any further packets it receives,

with headers indicating they belong to that connection.

A TCP reset kills a TCP connection instantly.

It is possible for a 3rd computer to monitor the TCP packets on the

connection,

and then send a “forged” packet containing a TCP reset to one or both

endpoints.

Who performs this attack?

Those with physical access to the wires/waves.

The Great Firewall of China and Iranian internet censorship mechanisms

are known to use TCP reset attack to interfere with and block

connections, as a method to carry out Internet censorship.

Comcast did this to people too:

In late 2007, Comcast began using forged TCP resets to cripple

peer-to-peer and certain groupware applications on their customers’

computers.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TCP_reset_attack#Comcast_Controversy

http://intronetworks.cs.luc.edu/current2/uhtml/tcpB.html#variants-and-alternatives

https://www.computer-networking.info/2nd/html/protocols/sctp.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transport_layer#Protocols

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Micro_Transport_Protocol

(uTP)

http://bittorrent.org/beps/bep_0029.html

https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc6817

Random examples of the hard way:

https://www.programcreek.com/python/example/7887/socket.SOCK_RAW

https://docs.python.org/3/library/struct.html

https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/struct-module-python/

Show these behave in wireshark:

Client

Transport/spoof_raw_UDP_client.py

Run the UDP server from the last lecture page before this.

A Packet sniffer for UDP (server)

Transport/spoof_raw_UDP_server.py

We can spoof port using this header.

Can we fake an a source IP address using just the TCP or UDP

transport layer header?

Do we have to fake any more headers?

Does the IP address go into the TCP header anywhere?

Do we have to fake any more headers to spoof a source IP address?

What is the difference between faking a DNS reply (as we did in

UDP),

and faking a source IP address?

++++++++++++ Cahoot-03-9

https://www.binarytides.com/raw-socket-programming-in-python-linux/

Transport/spoof_raw_TCP_socket.py

++++++++++++ Cahoot-03-10

https://www.binarytides.com/python-syn-flood-program-raw-sockets-linux/

Transport/spoof_syn_flood.py

In python (the easy way):

Transport/spoof_scapy.py

Scapy is really a nice library!

https://scapy.readthedocs.io/en/latest/

We’ll do an assignment with this upcoming.