without knowledge of the key,

it should be computationally infeasible to compute a valid tag of the given message,

even if we assume the adversary can forge the tag of any message except the given one.

“If you think technology can solve your security

problems,

then you don’t understand the problems,

and you don’t understand the technology.”

- Bruce Schneier

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bruce_Schneier

https://www.schneier.com/

All links on this page:

../../../ContactPublicKey.html

Chapter 11 - Message Authentication Codes:

https://github.com/crypto101/crypto101.github.io/raw/master/Crypto101.pdf

Overview:

https://www.comparitech.com/blog/information-security/encryption-types-explained/

Goals include:

Trust in message integrity and authenticity

Trust and communication with remote entities (key-distribution, and identity verification):

Secrecy of general data contents at rest and in transit

Better secrecy of human communications (Next lecture: DeniableForwardSecure.html.html)

First major high level goal, trust in message integrity and authenticity:

Comes in several flavors described below

1. MAC

2. AEAD

3. HMAC

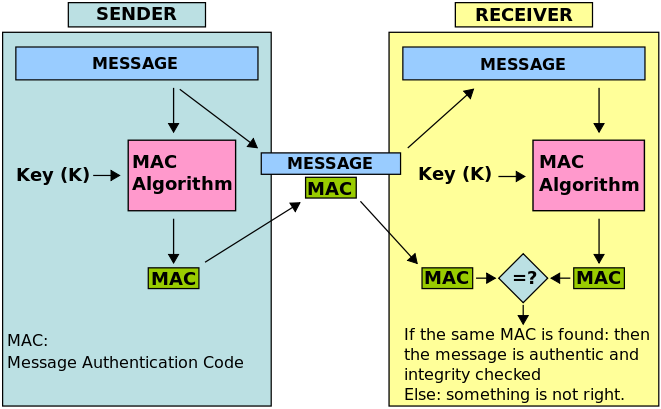

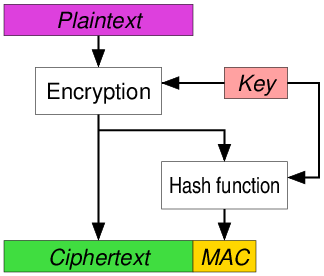

The first method of authentication is

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Message_authentication_code

Short piece of information used to authenticate a message,

sometimes know as a tag (t).

Confirms that a message came from a stated sender (its

authenticity),

and that the message not been changed (it’s integrity).

MAC value protects both a message’s data integrity as

well as its authenticity,

by allowing verifiers to detect any changes to the message content.

A MAC algorithm takes a message of arbitrary length,

and a secret key of fixed length, to produce a “tag”.

Sender and verifiers both possess the secret key.

A MAC algorithm also speficies a verification algorithm.

Verification takes the message, the key, and a tag,

and tells you if the tag is valid or not.

Note that we say “message” here instead of “plaintext” or

“ciphertext”.

This ambiguity is intentional.

We’re mostly interested in a MAC as a way to achieve authenticated

encryption,

so the message will usually be a ciphertext.

However, a MAC may still be applied to a plaintext message or

un-encypted file of any kind,

for the purpose of authentication.

A message authentication code system consists of three algorithms:

For a secure un-forgeable message authentication code,

without knowledge of the key,

it should be computationally infeasible to compute a valid tag of the

given message,

even if we assume the adversary can forge the tag of any message except

the given one.

While MAC functions are similar in ways to cryptographic hash

functions,

they possess different security requirements and inputs.

A MAC uses a key, while a hash itself does not.

Though, a key could be part of a larger crypto-system using a hash.

To be considered secure,

a MAC function must resist existential forgery under chosen-plain-text

attacks.

This means that even if an attacker has access to an “oracle”,

which possesses the secret key and generates a MAC for messages of the

attacker’s choosing,

the attacker cannot guess the MAC for other messages

(which were not used to query the oracle)

without performing infeasible amounts of computation.

Each differs:

MAC algorithms use symmetric encryption.

MAC values are both generated and verified using the same secret

key.

The sender and receiver of a message must agree on the same key,

before initiating communications, as with symmetric encryption.

Deniability of what was MAC’ed?

repudiate

rĭ-pyoo͞′dē-āt″

transitive verb

To deny, or reject the validity or authority of.

To reject emphatically as unfounded, untrue, or unjust.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Non-repudiation

Non-repudiation refers to a situation where a statement’s author cannot

successfully dispute its authorship or the validity of an associated

contract.

The term is often seen in a legal or security setting when the

authenticity of a signature is being challenged.

In such an instance, the authenticity is being “repudiated”.

Due to the shared key,

MACs do not provide the property of non-repudiation offered by

signatures.

If Alice and Bob are talking, they share the secret key.

Thus, Bob could fake what Alice said,

and Alice could fake what Bob said.

Secret keys can also be shared in groups,

meaning any group member could fake the message of any other group

member.

In the case of a network-wide shared secret key,

any user who can verify a MAC, is also capable of generating MACs for

other messages.

This is an interesting feature that can be exploited for deniable

authentication:

DeniableForwardSecure.html

Digital signatures uses asymmetric encryption.

Encrypting with the private key of a key pair generates a digital

signature.

Deniability of what was signed?

Private keys are held per individual or institution, uniquely.

Since this private key is only accessible to its holder,

a digital signature proves that a document was signed by none other than

the private key holder.

Thus, digital signatures do offer non-repudiation.

What you said is provably attributable to whoever held the key.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Cahoot_AppliedCryptoSystems_Mac-Hash

Why do you think we use a key in MAC,

even though we’re not encrypting?

The second method of authentication is:

“When it comes to designing secure protocols,

I have a principle that goes like this:

if you have to perform any cryptographic operation,

before verifying the MAC on a message you’ve received,

it will somehow inevitably lead to doom.”

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moxie_Marlinspike

Also the original author of the double-ratchet algorithm up next:

DeniableForwardSecure.html

https://moxie.org/blog/the-cryptographic-doom-principle/

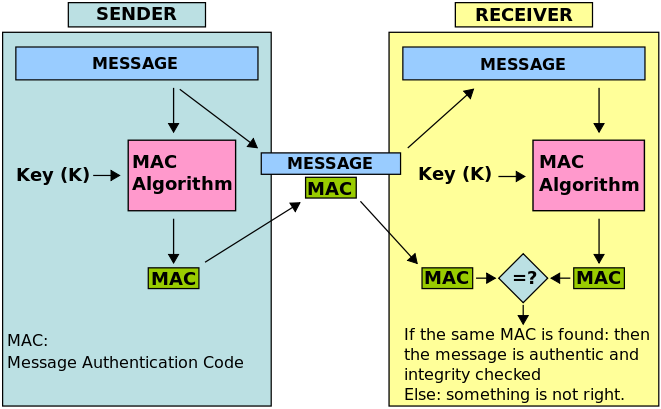

States that the following AEAD methods are ranked in the order shown

below:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Authenticated_encryption

Comes in several broad flavors (detailed here)

You authenticate and encrypt the plain-text separately.

C = cipher-text

P = plain-text

t = tag, a.k.a. the MAC

K = a key, separate or the same for each process

C = E(KC , P),

t = MAC(KM, P),

and you send both cipher-text C and tag t.

This is how SSH does it…

(I don’t think they’ve updated,

but they may have since I wrote this).

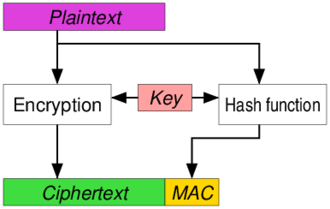

You authenticate the plain-text,

and then encrypt the combination of the plain-text and the

authentication tag.

t = MAC(KM, P ),

C = E(KC, P || t),

and you only send C.

You don’t need to send t,

because it’s already an encrypted part of C.

This is how TLS used to do it,

unless it’s doing HMAC (probably the most secure),

or now the best AEAD method below (EtM).

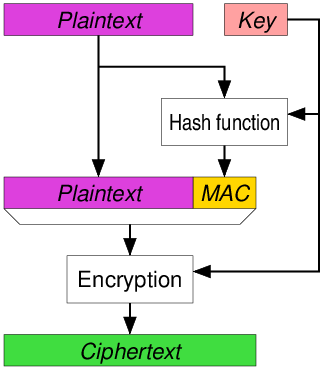

You encrypt the plain-text,

compute the MAC of that cipher-text.

C = E(KC, P),

t = MAC(KM, C),

and you send both C and t.

This is how IPSec does it,

and modern TLS is now capable of this too.

TLS1.3 defaults to this.

The third method of authentication is:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMAC

Also knownn as:

Keyed-hash message authentication code

Hash-based message authentication code

What?

HMAC is a generalized type of message authentication code (MAC).

It uses both a cryptographic hash function and a secret cryptographic

key.

Historical goals?

Develop a meta-MAC system derived from a cryptographic hash code.

Any cryptographic hash function, such as SHA256 or

SHA-3,

should be able to be used in the calculation of an HMAC.

It may be used to simultaneously verify data integrity,

and perform authentication of a message,

as with any MAC.

Why?

Cryptographic hash functions generally execute quickly.

Library code is widely available.

A meta-MAC system can out-live each hash function itself.

SHA-1 was not deigned for use as a MAC,

because it does not rely on a secret key.

Practical notes:

Issued as RFC2014.

HMAC was chosen as the mandatory-to-implement MAC for IP security in

IPv6 (IPSec).

Used in other Internet protocols such as

Transport Layer Security (TLS) and

Secure Electronic Transaction (SET).

To use, without modifications, available standard hash

functions

To use and handle keys in a simple way:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/KISS_principle

To allow for easy, modular, replaceability of the embedded hash

function,

in case faster or more secure hash functions are found or

required.

To preserve the original performance of the hash function,

without incurring a significant degradation.

To have a well-understood, strong authentication mechanism,

based on reasonable assumptions about the embedded hash function.

The underlying hash function doesn’t even have to be collision resistant

for HMAC to be secure!

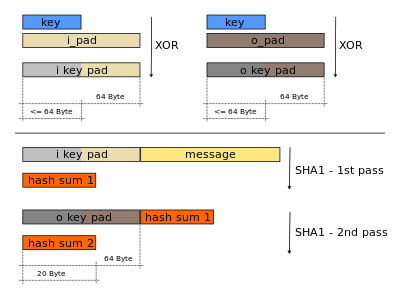

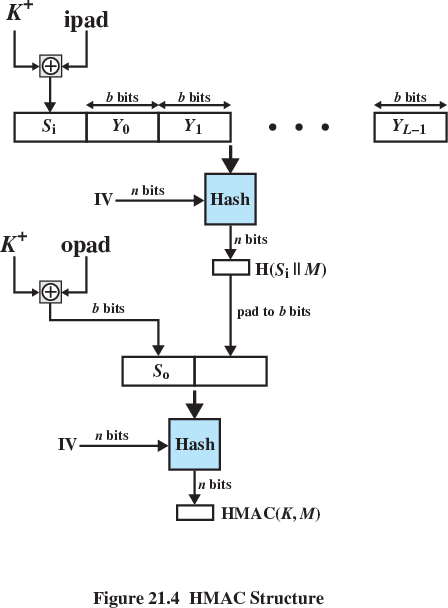

Nested, repeated hashing, with a key as additional input:

The biggest difference between HMAC and prefix-MAC or its

variants,

is that the message passes through a hash function twice,

and is combined with a key before each pass.

\(HMAC(K,m)=H{\Bigl ((K'\oplus

opad)\|H{\bigl (}(K'\oplus ipad)\|m{\bigr )}{\Bigr

)}}\)

H is a cryptographic hash function,

m is the message to be authenticated,

K is the secret key.

K’ is another secret key,

derived from the original key K

(by padding K to the right with extra zeroes,

to the input block size of the hash function,

or by hashing K if it is longer than that block size).

|| denotes concatenation,

\(\oplus\) denotes bitwise exclusive or

(XOR),

opad is the outer padding,

consisting of repeated bytes,

valued 0x5c, up to the block size, and

ipad is the inner padding,

consisting of repeated bytes,

valued 0x36, up to the block size.

H = embedded hash function (e.g., SHA)

M = message input to HMAC

(including the padding specified in the embedded hash function)

Yi = ith block of M, 0 <= i <= (L - 1)

L = number of blocks in M

b = number of bits in a block

n = length of hash code produced by embedded hash function

K = secret key;

if key length is greater than b,

the key is input to the hash function to produce an n-bit key;

recommended length is >= n

K+ = K padded with zeros on the left,

so that the result is b bits in length

Discussion question:

Why do you think we hash twice,

with different inputs?

Trivial mechanisms for combining a key with a hash function result in vulnerabilities and attacks:

MAC = H(key || message)

This method suffers from a serious flaw:

with most hash functions,

it is easy to append data to the message,

without knowing the key and obtain another valid MAC

(“length-extension attack”).

MAC = H(message || key)

Suffers from another problem.

An attacker who can find collision in the (un-keyed) hash function has a

collision in the MAC.

Two messages m1 and m2 yielding the same hash,

will provide the same start condition to the hash function

before the appended key is hashed,

hence the final hash will be the same.

MAC = H(key || message || key)

is better, but various security papers have suggested vulnerabilities

with this approach,

even when two different keys are used.

HMAC = H(key || H(key || message))

No known extension attacks have been found against this current HMAC

specification.

The outer application of the hash function masks the intermediate result

of the internal hash.

The values of ipad and opad are not critical to the security of the

algorithm,

but were defined in such a way to have a large Hamming distance from

each other,

and so the inner and outer keys will have fewer bits in common.

The security reduction of HMAC does require them to be different in at

least one bit.

The Keccak hash function, that was selected by NIST as the SHA-3

competition winner,

doesn’t need this nested approach, and can be used to generate a

MAC,

by simply prepending the key to the message,

as it is not susceptible to length-extension attacks.

SHA-3 is the only of the hash functions that we have covered that is

possibly secure on its own!

Security depends partly on:

the cryptographic strength of the underlying hash function,

and the size of the key used.

For a given level of effort,

on messages generated by a legitimate user,

and seen by the attacker,

the probability of successful attack on HMAC is equivalent to one of the

following attacks on the embedded hash function:

Attacker computes output,

even with random secret IV.

Brute force key O(2n).

Or attacker finds collisions in hash function,

even when IV is random and secret:

i.e., find M and M’ such that H(M) = H(M’).

Birthday attack O(2n/2).

We just covered plain MAC, asymmetric signing, AEAD, and improved

HMAC.

HMAC with a good hash is probably the most secure,

though AEAD is faster,

and good enough for most applications.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transport_Layer_Security#Data_integrity

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Cahoot_AppliedCryptoSystems_AEAD

Trust in message integrity and authenticity:

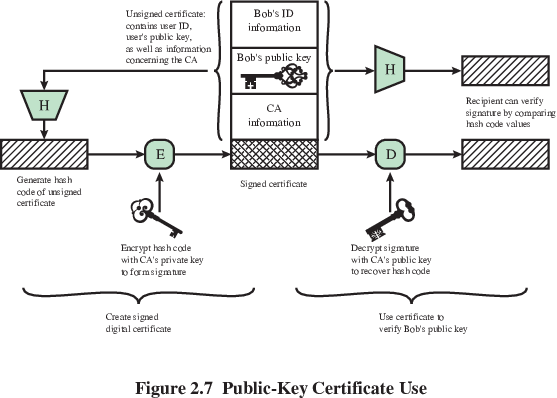

In public-key encryption schemes,

the order of encryption and decryption algorithms can be reversed:

\(E_{P_{B}}(D_{S_{B}}(M)) = M\)

If Bob intends to prove he is the author of message M,

he can first compute:

\(S=D_{S_{B}}(M)\)

S serves as a digital signature for message M.

Bob sends S and M to Alice.

Alice can recover M by performing:

\(M = E_{P_{B}}(S)\)

Alice is assured M is authored by Bob.

Bob’s signature will be as least as long as his message.

This exact construction is not used in practice,

for reasons presented now:

Cryptographic hash functions can reduce the size of

data being signed.

The most important property of a hash function is being

one-way:

Easy to compute, but hard to invert.

Given M, it is easy to compute h(M).

Given y = h(M), it is hard to find M.

Modern cryptographic hash functions, such as SHA2,

are believed to be securely one-way.

Given a message M,

Bob computes:

\(S = E_{S_{B}}(h(M))\)

To verify S on M,

Alice computes h(M),

and checks against processed signature:

\(D_{P_{B}}(S) = h(M)\)

Cryptographic hash functions are collision

resistant.

Given M, it is hard to find a different message M’,

such that h(M’) = h(M).

This property makes the forger’s job even more difficult.

Trust and communication with remote entities (key-distribution, and identity verification):

Discussion question:

Would you think it possible to prove that:

you are not colorblind?

you are colorblind?

What if the person you were proving it to was, themselves,

colorblind?

DH and RSA were the first major innovation in modern

cryptography,

and the ZK-proof and challenge-response were the

2nd,

extending and applying some of those ideas!!!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Challenge%E2%80%93response_authentication

Bob issues a challenge to Alice.

If Alice can solve the challenge,

Alice is authenticated by Bob’s system.

For authentication purpose,

only Alice should know how to solve the challenge.

From observing the whole process,

no one should know how to solve the challenge,

except for Alice

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zero-knowledge_proof

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Cahoot_AppliedCryptoSystems_USB.toml

Alice wants to prove to Bob that she knows a secret.

If a proof is to be Z.K.,

Bob accepts the proof without knowing the secret itself.

Problem:

Imagine your friend is red-green color-blind,

while you are not.

You have two cards:

one red and one green, but otherwise identical.

To your friend they seem completely identical,

and he is skeptical that they are actually distinguishable.

You want to prove to him that:

each card is in fact differently-colored,

but nothing else.

Namely, you do not want to reveal:

which one is the red, and which is the green card.

Solution:

You give the two cards to your friend.

He puts them behind his back.

Next, he brings one card out from behind his back, and displays

it.

He then places it behind his back again,

Then he chooses to reveal just one of the two cards, picking one of the

two at random with equal probability.

He will ask you, “Did I switch the card?”

By looking at their colors,

you can of course say with certainty whether or not he switched

them.

On the other hand, if they were the same color and hence

indistinguishable,

there is no way you could guess correctly with probability higher than

50%.

This whole procedure is then repeated as often as necessary.

If you and your friend repeat this “proof” multiple times (e.g. 100

times),]

your friend should become convinced (formally “completeness”),

that the cards are indeed differently colored

The probability that you would have randomly succeeded at identifying

all the switch/non-switches is close to zero (formally “soundness”).

The above proof is zero-knowledge,

because your friend never learns which card is green, and which is

red.

Your friend gains no knowledge about how to distinguish the cards.

Alice wants to prove to bob that,

she is who she says she is

(and thus owns her private key).

Alice generates a private-public key pair.

Alice sends Bob the public key only

(keeping her private key to herself).

How does Alice prove to Bob that she knows that corresponding private

key?

Bob sends a random number encrypted to Alice using her key.

Who can decrypt it?

Bob?

Alice?

Anyone else?

Alice generates a private-public RSA key pair.

Alice logs into her remote account managed by Bob the sysadmin,

e.g., using password based authentication.

Alice stores her public key (N, e) remotely,

in the home directory of the OS within her remote account (in

~/.ssh/).

To initiate authentication,

Alice sends her login ID to Bob to start an authentication

procedure.

Bob uses Alice’s previous stored public key to compute:

\(c = E_{pk_a}(r)\)

where r is randomly chosen from \(\mathbb{Z}_N\),

and sends c to Alice.

Alice computes:

\(r' = D_{pr_a}(c)\)

and sends r’ to Bob.

Bob verifies r=r’.

If r=r’,

Bob authenticates Alice.

Does it matter if the connection is encrypted?

For example, could an ISP “replay” the answer?

Comes in two theoretically identical flavors:

1. Server authenticates client (you) — easy in practice.

2. Client (you) authenticates server — hard in practice.

Secure passwords are hard to remember.

Alternatively, a challenge-response scheme can be used for

authentication purposes.

Once set-up, a password is no longer needed.

Bob wants to remotely login “server_bob.device.mst.edu”,

with user id “bob87” from his local machine “local_bob”.

The following steps are performed on “local_bob”:

#!/bin/bash

# Step 1: Generate new key on your local machine

ssh-keygen -t rsa -b 4096

# to see your new keyfiles on your local machine

ls ~/.ssh/

# Step 2: Copy key to server a) automatic or b) manual

# a. automatic

ssh-copy-id "bob87@ServerBob.device.mst.edu"

# b. manual copy of PUBLIC KEY to server

cat ~/.ssh/id_rsa.pudb # on local machine

mkdir ~/.ssh/ # on remote machine

chmod 700 ~/.ssh # this is important.

touch ~/.ssh/authorized_keys

chmod 600 ~/.ssh/authorized_keys #this is important.

# using your method of choice, put your cat'ed key in that file

# or a one-liner (if folder exists):

cat ~/.ssh/id_rsa.pub | ssh <user>@<hostname> 'cat >>.ssh/authorized_keys && echo "Key copied"'

# one-liner if folder does not exist on remote machine:

cat ~/.ssh/id_rsa.pub | ssh <user>@<hostname> 'umask 0077; mkdir -p .ssh; cat >> .ssh/authorized_keys && echo "Key copied"'Why is this simple and effective in practice?

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Cahoot_AppliedCryptoSystems_zk

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_key_certificate

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/X.509

https://letsencrypt.org

https://letsencrypt.org/getting-started/

https://letsencrypt.org/how-it-works/

https://letsencrypt.org/docs/faq/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transport_Layer_Security

Example certificate

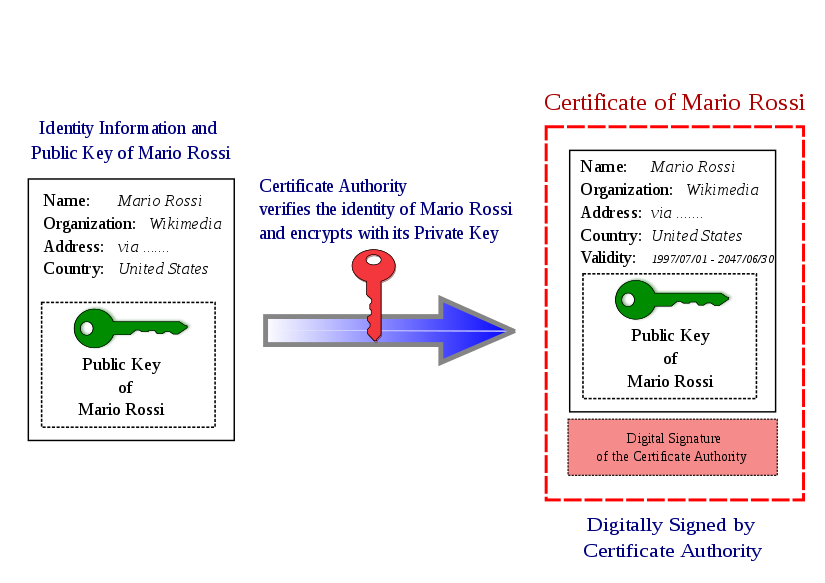

A public key certificate, also known as a digital certificate or

identity certificate,

is an electronic document used to prove the binding betwee a

public/private key-pair and meta-data,

the operable definition of ownership.

When public-key crypto-system is used to share a secret key,

how does Alice know if PB is actually from Bob?

How do you know the server you exchang keys with is really the

end-server,

and not acting as a MitM (your ISP maybe)?

Alternatively, if there many Bobs,

how does Alice know which is the right one?

Questions:

What about meeting bob in person?

Is doing so for every entity you want to connect to practical?

What if you trusted a friend,

who visited everyone on the planet for you,

to get them to prove the binding between their real identity and their

key?

Would you trust that friend?

What if that friend was the government?

What if that friend was a big company?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Certificate_authority

A trusted authority purports to enable verifying the true identity of

people (or entities).

Such an authority can digitally sign the concatenation of:

1) a statement about that person’s identity,

2) their public key.

Sample statement:

“The Bob who lives on 11th Main Street in Rolla was born on

April 5, 1986,

and has this entire public key

PB,

and I stand by this certification until December 31,

2011.”

Such a statement is called digital

certificate,

if it combines

1) a public key with

2) identifying info about the subject who has that key.

A trusted authority who issues such a certificate is called a certificate authority (CA).

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Cahoot_AppliedCryptoSystems_CA

Alice needs only to trust the CA,

and know the CA’s public key,

to trust everyone the CA provides certificates for.

The number of CAs should ideally be small.

Is it actually…?

The public keys of commonly accepted CAs are often packaged with the

operating system or browser

Why should you trust those?

What if you didn’t?

How would you validate the remote keys manually?

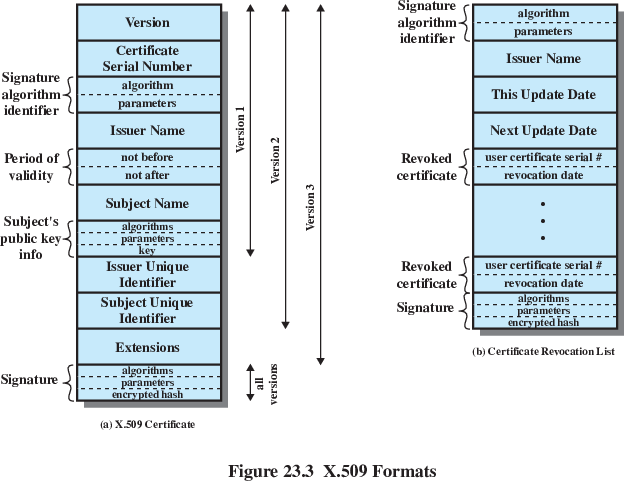

The following data are signed as one unit:

The set of hardware, software, people, policies, and

procedures,

needed to create, manage, store, distribute, and revoke digital

certificates.

Developed to enable secure, convenient, and efficient acquisition of

public keys.

“Trust store”: A list of CA’s and their public keys.

Provides a system for semi-distributed trust in the key-ID binding of

remote entities

X.509 is one of the PKI standards.

It specifies the format of digital certificates.

The X.509 standard is described in the IETF document RFC 5280 (recent

update in RFC 6818).

The most widely accepted format for public-key certificates.

Certificates are used in most network security applications,

including:

IP security (IPSEC),

TLS,

Secure electronic transactions (SET),

S/MIME,

eBusiness applications.

What is a certificate?

Public key bound with identity information of the key’s owner.

Both data and key signed by a trusted 3rd party.

Typically the third party is a CA that is trusted by the user

community,

such as a government agency, telecommunications company,

financial institution, or other trusted peak organization.

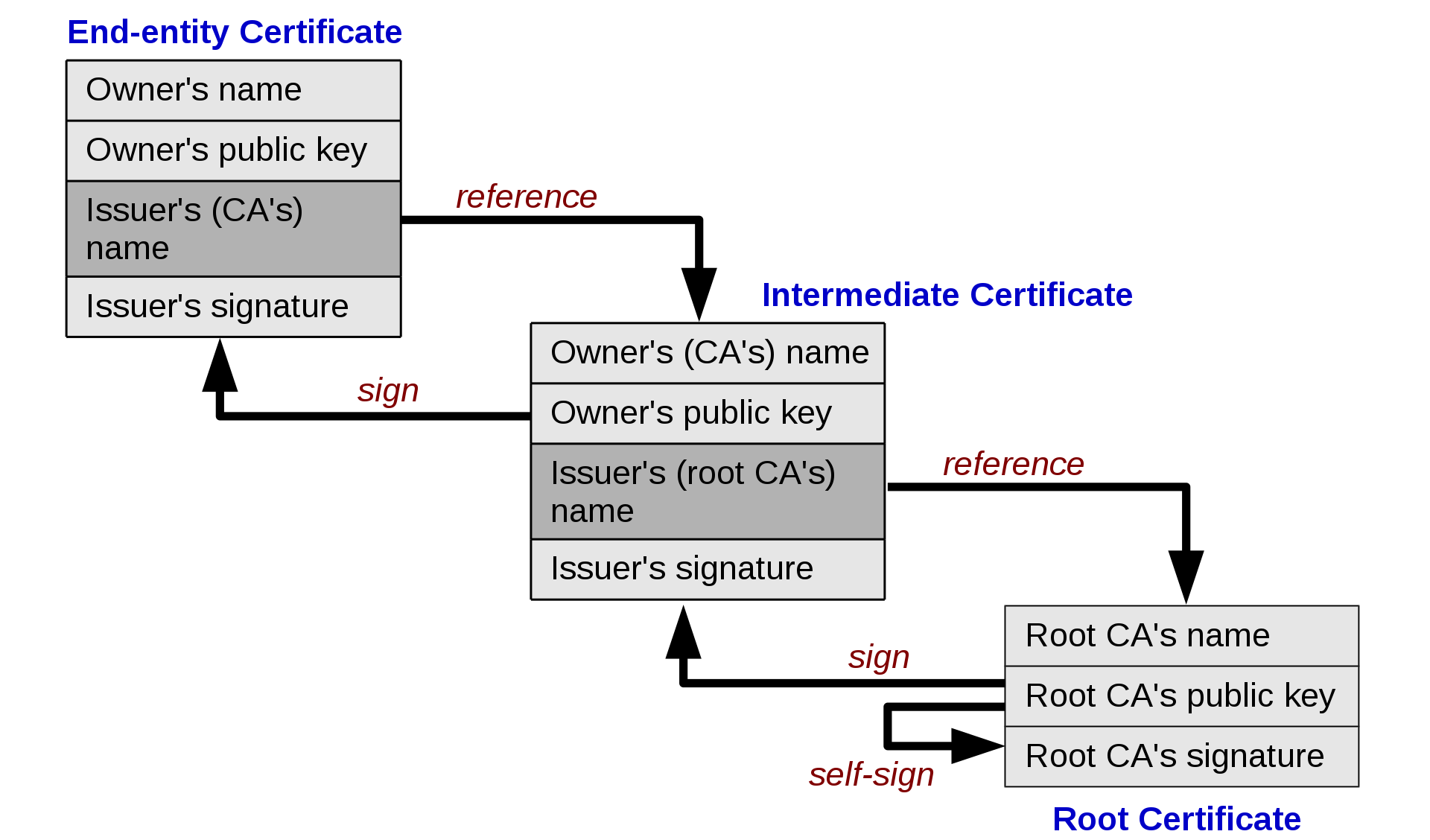

This trust can be chained across multiple verifiers,

with some “root of trust”:

Left is your web server’s certificate,

right is root certificate

(present in the client, who is not depicted)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trust_anchor

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Root_certificate

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chain_of_trust

In cryptographic systems with hierarchical structure,

a trust anchor is an authoritative entity for which trust is assumed and

not derived.

In X.509 architecture,

a root certificate would be the trusted anchor,

from which the whole chain of trust is derived.

Most operating systems provide a built-in list of self-signed root

certificates,

to act as trust anchors for applications.

Browsers, e.g., the Firefox web browser, also provides its own list of

trust anchors.

The end-user of an operating system or web browser implicitly trusts in

the correct operation of that software,

and the software manufacturer in turn is delegating trust for certain

cryptographic operations to the certificate authorities responsible for

the root certificates.

What happens if a root CA decides to trust a new intermetiate

CA?

What if that new intermediate has questionable business practices?

Do you also trust the new one automatically?

Can a certificated issued by a CA forged?

Creating a rogue CA certificate by finding a hash collision:

http://www.win.tue.nl/hashclash/rogue-ca/

An attacker breached the account of a re-seller of Comodo-signed

certificates:

http://blogs.comodo.com/it-security/data-security/the-recent-ra-compromise/

My site

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/X.509

https://www.qubes-os.org/

What about the Qubes Tor/onion site:

http://qubesosfasa4zl44o4tws22di6kepyzfeqv3tg4e3ztknltfxqrymdad.onion/

Viewable in the Tor browser or any browser routed through Tor:

https://www.torproject.org/download/

Does it need a cert?

Trust and communication with remote entities (key-distribution, and identity verification):

The means of delivering a key to two parties that wish to exchange

data,

without allowing others to see the key.

Two parties (Alice-A and Bob-B) can achieve this by either:

Key could be selected by A and physically delivered to B.

Third party could select the key and physically deliver it to A and B.

If A and B have previously and recently used a key,

one party could transmit the new key to the other,

encrypted using the old key.

If A and B each have an encrypted connection to a third party

C,

C could deliver a key on the encrypted links to A and B.

Use a public-key key protocol,

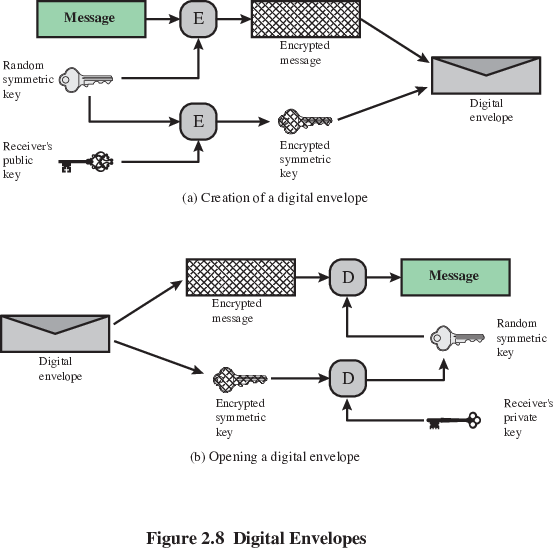

or public key encryption as a digital envelope (see PGP

below).

Protects a message without needing to pre-exchange as secret key.

Equates to the same thing as a sealed envelope containing an unsigned

letter.

This is used in both TLS (session key exchange) and PGP/GnuPG (both

below).

Why not just use asymmetric cryptography for all data?

Secrecy of data contents at rest and in transit:

../../Networking/Content/Security.html

(in particular, the section on TLS)

Secrecy of data contents at rest and in transit:

It is common to encrypt transmitted data.

It is much less common to encrypt stored data.

There is often little disk-access protection,

beyond domain authentication and operating system access controls.

Data are archived for indefinite periods.

Even though seemingly erased,

until disk sectors are reused,

data are recoverable.

Approaches to encrypt stored data:

Starts with using a reasonable operating system…

Modern BSD-Unix/Linux can easily encrypt the whole disk,

with something like LUKS (AES-512).

https://gnupg.org/

for encrypting/signing data for long-term

archival

(and emails, though less ideally so).

See reading at: ../../../ContactPublicKey.html

The symmetric encryption is valid, strong.

What is the weakest link?

Is this forward-secure (protect the past, under key-compromise)?

Do people feel pgp easy is to use?

Can you both trust the source,

and deny what was said (deniable authentication)?

The first for-the-public “military grade encryption” in popular

use.

PGP stands for “Pretty Good Privacy”.

It was developed originally by Phil Zimmerman.

In its incarnation as OpenPGP,

it has become an open-source standard,

described in RFC 4880.

PGP is widely used for protecting data in long-term storage.

We will discuss how PGP secures emails.

Authentication

Confidentiality

Compression

E-Mail Compatibility

Segmentation

Sender authentication consists of:

the sender attaching a digital signature to an email, and

the receiver verifying the signature using public-key cryptography:

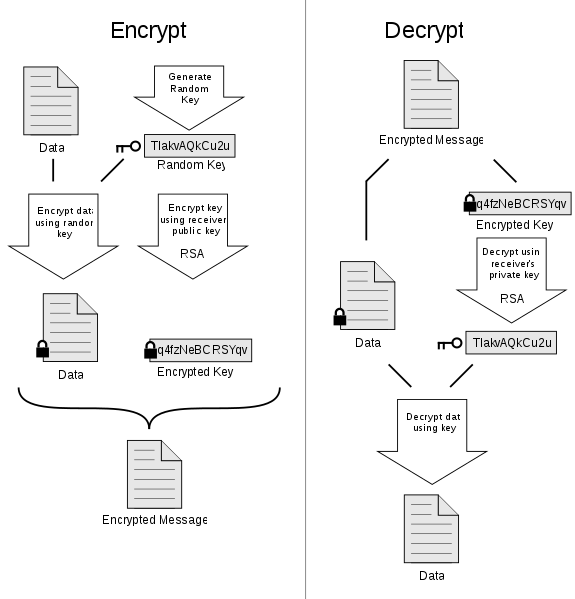

PGP uses a digital envelope with symmetric-key encryption for data

confidentiality

(the key for that is encrypted using asymmetric methods),

and has a choice of many different secure block-cipher algorithms:

CAST, IDEA, 3DES, Blowfish, Twofish, AES, Camelia

The encryption key, called the session key,

is generated for each email message separately.

Cipher Feedback Mode (CFB) is used for encryption.

The session key is encrypted using RSA with the receiver’s public key

(digital envelope).

What is put on the wire is the email message after it is encrypted first

with the session key,

which is encrypted receiver’s public key.

If confidentiality and sender-authentication are needed

simultaneously,

a digital signature for the message is generated using the hash code of

the message plain-text,

the signature is appended to the email message before it is encrypted

with the session key.

In default mode,

PGP compresses the email message,

after appending the signature,

but before encryption.

This makes long-term storage of messages more efficient.

The ZIP algorithm is the default used for compression.

Since encryption results in arbitrary binary strings,

and network message transmission is character oriented,

we must represent binary data with ASCII strings.

PGP uses Base64 encoding for this reason.

For long email messages,

many email systems place restrictions on how much of the message will be

transmitted as a unit.

For instance, certain email systems segment long messages into 50,000

byte segments,

and transmit each separately.

PGP has built-in tools for such segmentation and re-assembly.

Key Management Issues

Web of Trust

Public key encryption is the foundation to PGP.

People may have multiple public and private keys.

An individual may wish to retire an old public key.

To allow for a smooth transition,

the old and the new public keys need to be available for a while.

Thus, under PGP,

the receiver of a message may have stored multiple public keys for a

given sender.

This creates the following problems:

When PGP uses one of the public keys made available by the

recipient,

how does the recipient know which public key it is?

When the sender uses one of the multiple private keys,

that the sender has for signing the message,

how does the recipient know which is the corresponding public key?

The problems can be solved by the sender also sending along the

public key used.

But this is wasteful in space because of the size of the RSA public

keys.

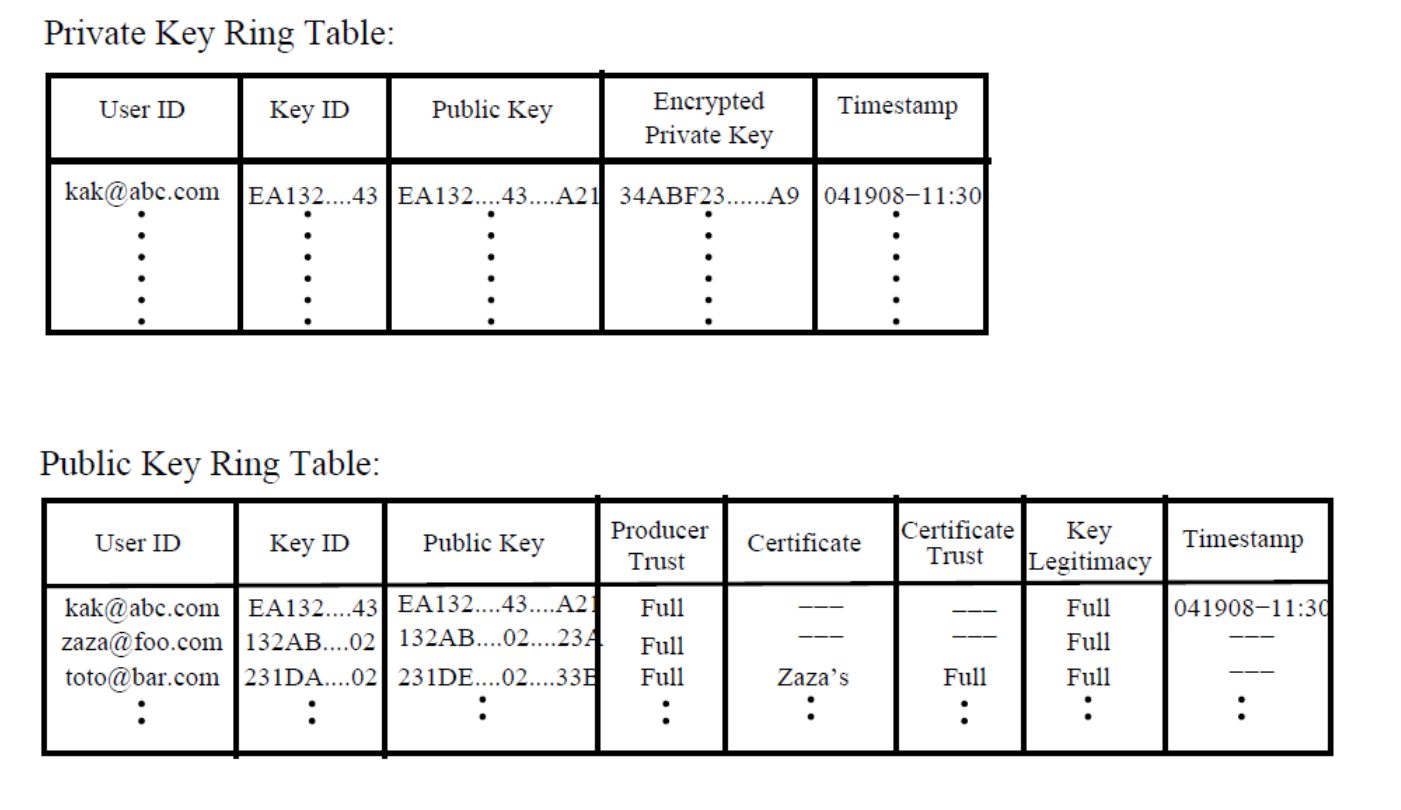

PGP solves this problem by using the notion of a relatively short key

identifiers (key ID) and requiring that every PGP agent maintain.

Its own list of paired private/public keys in what is known as the

private Key Ring.

A list of the public keys for all its email correspondents in what is

known as the Public Key Ring.

The keys for a particular user are uniquely identifiable through a

combination of the user ID and the key ID

The key ID associated with a public key consists of its least

significant 64 bits

For security reasons,

PGP stores the private keys in the ring in encrypted form,

so that the keys are only accessible to the user who owns them.

The attributes “Producer Trust”, “Key Legitimacy”, “Certificate”,and

“Certificate Trust”

are to assess how much trust to place in the public keys of other

users.

https://openpgpjs.org/

https://protonmail.ch/

https://www.mailvelope.com/en/

Producer Trust:

indicating the extent to which the owner of a particular public key can

be trusted,

to sign other certificates.

This generally has one of three values:

full, partial, or none.

Certificate:

holding the certificate(s) that authenticates the entry in the public

key field.

Certificate Trust:

indicating how much trust a user wants to place in the entry in the

Certificate field.

Key Legitimacy:

derived by PGP from the value(s) stored for the Certificate Trust

field(s),

and a predefined weight for each symbolic value for certificate

trust.

A bottom-up approach to establishing trust.

A user’s public key can be signed by any other user.

It is possible that a user will receive two different certificates for a

new email correspondent:

one that the receiver will trust fully,

the other that the receiver may trust only partially.

Whether or not to trust such a potential email correspondent,

is up to the receiver of the certificates.

Free publicly available PGP Key-servers exist at various places in

the world.

In order to upload the public key to a key server,

we can create a GPG (Gnu Privacy Guard) key and upload to

pgp.mit.edu, for example

An extended video, if you want to learn more about gpg (gnupg):

https://begriffs.com/posts/2016-11-05-advanced-intro-gnupg.html

Modern discussions/criticisms of PGP

https://latacora.micro.blog/2019/07/16/the-pgp-problem.html

https://blog.filippo.io/giving-up-on-long-term-pgp/

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Cahoot_AppliedCryptoSystems_gpg2