Previous: VirtualMachines.html

This is Tux the Linux mascot…

https://eylenburg.github.io/os_familytree.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Unix

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unix

(see tree: e.g., FreeBSD yielded MacOS)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Linux_distributions

(see tree: e.g., RedHat-Fedora, OpenSuse, Debian, etc.)

http://etutorials.org/Linux+systems/

http://labor-liber.org/en/gnu-linux/introduction/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unix_philosophy

Excerpts from the Unix philosophy:

Write programs to handle text streams,

because that is a universal interface.

Combine “small, sharp tools” and the use of common underlying

format,

the line-oriented, plain text file” to accomplish larger tasks.

Store data in flat text files.

Another major tenet of the philosophy is to use plain text

(i.e., human readable alphanumeric characters)

rather than binary files (which are not fully human readable)

to the extent possible for the inputs and outputs of programs,

and for configuration files.

This is because plain text is a universal interface;

that is, it can allow programs to easily interact with each other,

in the form of text outputs and inputs,

in contrast to the difficulty of mutually incompatible binary

formats,

and because such files can be easily interfaced with humans.

The latter means that it is easy for humans to:

study, correct, improve, and extend such files,

as well as to port (i.e., modify) them to new platforms

(i.e., other combinations of operating systems and hardware).

Unix tradition strongly encourages writing programs that read and

write:

simple, textual, stream-oriented, device-independent formats.

Under classic Unix, as many programs as possible are written as simple

filters,

which take a simple text stream on input,

and process it into another simple text stream on output.

Despite popular mythology,

this practice is not favored because Unix programmers hate graphical

user interfaces.

It’s because if you don’t write programs that accept and emit simple

text streams,

then it’s much more difficult to hook the programs together.

Text streams are to Unix tools,

as messages are to objects, in an object-oriented setting.

The simplicity of the text-stream interface enforces the encapsulation

of the tools.

More elaborate forms of inter-process communication,

such as remote procedure calls,

show a tendency to involve programs with each others’ internals too

much.

To make programs composable, make them independent.

A program on one end of a text stream should care as little as possible

about the program on the other end.

It should be made easy to replace one end with a completely different

implementation,

without disturbing the other.

+++++++ Discussion question

Can you think of any other benefits of using plain text for APIs, data

storage, or inter-process communication?

Two major options (remote or local):

$ ssh into an MST Campus Linux machine (The Mill,

for example):

../../../ClassGeneral/WorkingEnvironment.html

$ ssh into some other remote computer:

Try this game after completing the bash tutorials below.

http://overthewire.org/wargames/bandit/bandit0.html

Use a graphical web browser interface to remote-desktop into a

virtual machine.

../../../ClassGeneral/WorkingEnvironment.html

Local virtual machine (VM):

VirtualMachines.html

Use a container:

Install podman, docker, or singularity .

At your terminal, run:

$ podman run -it --rm fedora:latest

Here is more information on how to do that:

../../../ClassGeneral/WorkingEnvironment.html

Install Linux bare-metal on a USB stick, leaving your hard-drive un-touched:

3a. Option 1: you can just get a live ephemeral drive.

3b. Option 2: you could install that to another USB drive,

so your changes are persistent across reboots.

This only temporarily requires a second USB drive.

Install Linux bare-metal, on your main hard drive as the

only OS:

Follow up on the first step of the USB stick option,

but instead, choose to install to your hard drive.

Install Linux bare-metal, on your main hard drive as a

dual-boot:

partition using Linux on a USB drive,

install Windows on a limited partition,

and lastly, install Linux, and the boot manager on the MBR.

For huge percentage of development in many fields of software

development,

it’s all or mostly Unix-like environments.

Consider which devices out there are computers.

This includes servers, firewalls, phones (which are computers),

embedded devices (which contain computers), refrigerators,

toasters,

hosted containers, gaming devices, etc.

The vast majority of the computers in the world run a similar

shell,

on a Unix or Linux derived operating system, by far.

In computer security, the primary repositories of both defensive and

offensive security software,

exist as open source code that runs in a Unix-derived environment.

These OS’s support and integrate virtualization by design,

enabling novel web/network engineering.

In most Linux and Unix distributions, you can read the code, fix the

code,

and “trust” that the code does what you think it does:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open_source

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open-source_software

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open-source-software_movement

Transparency is a good thing!

Unix/Linux is THE status-quo for software development and

testing.

This list could continue for pages… just “duck” it:

https://duckduckgo.com/?q=why+learn+linux

Read the following tutorial in full!

https://ryanstutorials.net/linuxtutorial/

https://ryanstutorials.net/linuxtutorial/cheatsheet.php

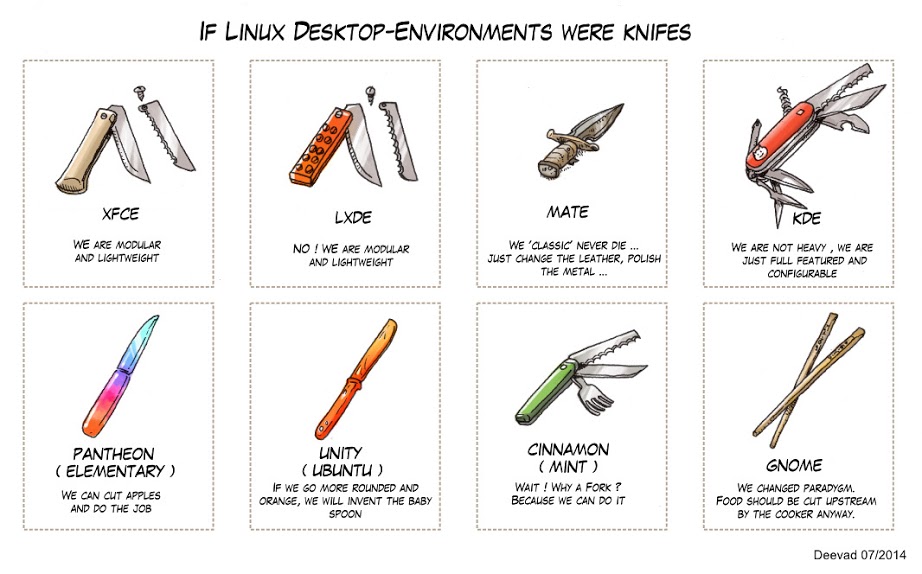

Though it might initially seem important,

it doesn’t really matter which front-end desktop environment (DE) you

pick.

You can install multiple, switch back-and-forth, etc.

Pick one, pick all, it does not matter; just try some out.

Though it might initially seem important,

it doesn’t really matter too much which distribution you pick (within

reason).

Here are some common choices:

LinuxBash/Fedora.html

This is testing for Red Hat and also offers Fedora Security Labs,

not-quite bleeding edge but up-to-date, minimal, good,

inconvenient versioned releases, mediocre documentation.

Almost bleeding edge, corporate go-to, minimal docs/support.

LinuxBash/OpenSuse.html

Up-to-date, corporate go-to, great docs/support, recommended.

For an introductory experience on your own machine, this is a nice

choice.

It’s a “rolling release” so you don’t need to re-install at new

versions,

best documentation out there, not-quite bleeding edge but

up-to-date.

LinuxBash/Debian.html

Old, conservative, mother distribution,

experiencing “death by committee” despite progressive intent…

Inconvenient versioned releases, ancient software options,

ancient out-of-date documentation, OK but not recommended.

LinuxBash/Kali.html

Based on Debian, with more security-related packages,

inconvenient versioned releases, partially up-to-date, unstable,

inconsistent, OK but not recommended unless you need some particular

package in it.

insecure offensive/forensics security distribution based on Debian.

Ubuntu (or anything else Debian-derived).

Don’t bother over just using Debian itself.

Computers store files.

Files can be organized into directories, also know as folders.

Linux is designed to be a multi-user system.

The system administrator (root) controls the root files.

Each user only controls their own little home directory.

This is know as “separation of privilege” in operating system

security.

…

…

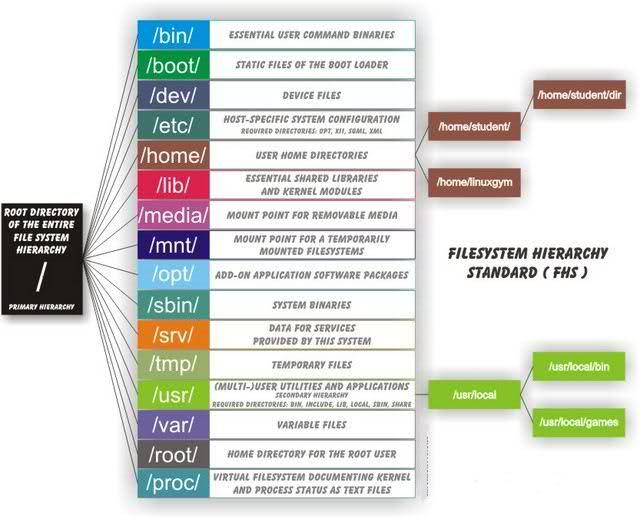

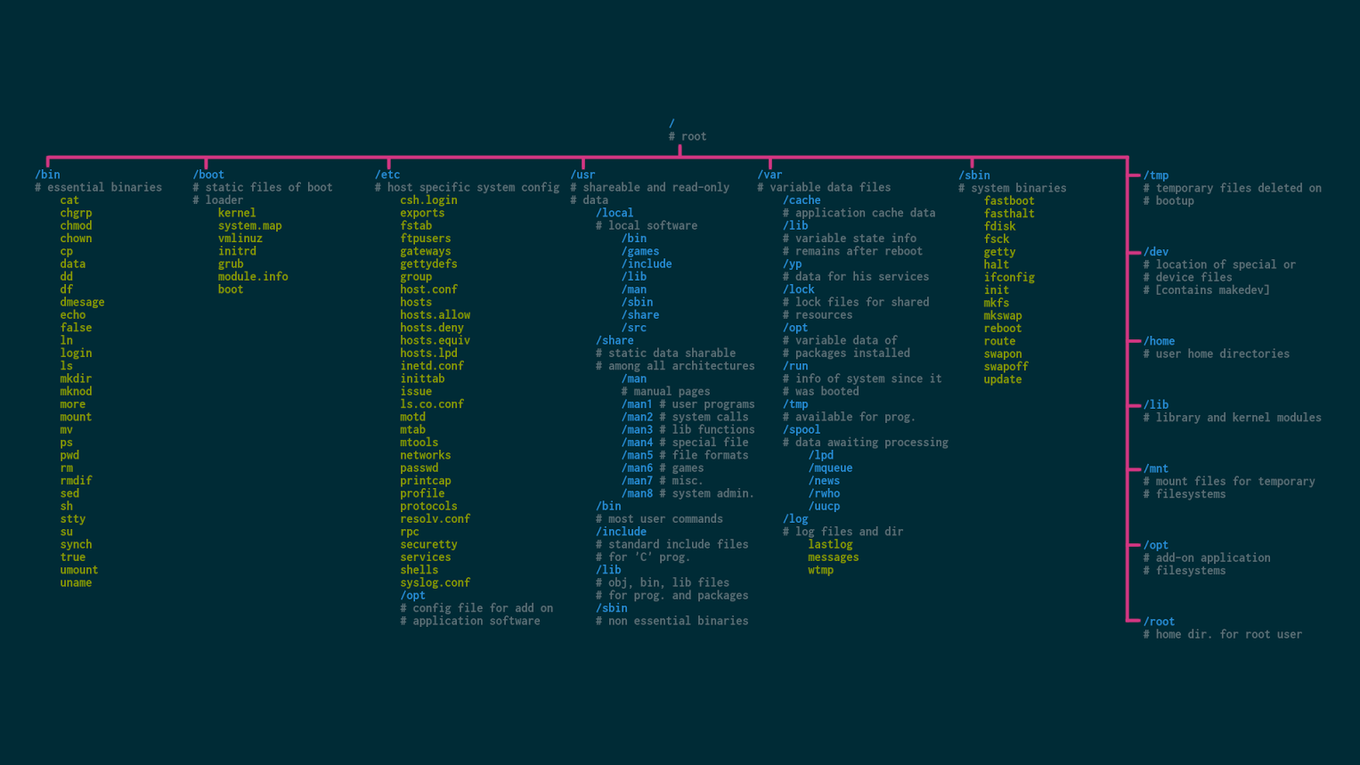

In general, root refers to the base or origin of a branching

system.

Disclaimer: root is also the name of a special user

account,

the system administrator, who can access the root directory,

and do anything on the computer!

Here, we’re talking about the base of the Unix/Linux directory

tree,

with a standardized organization:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Root_directory

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Filesystem_Hierarchy_Standard

/home/ may be aliased as ~ or

$HOME

It contains all your stuff, documents, photos, whatever you store.

As a non-administrative user,

it is the ONLY place you are intended to explicitly have access to.

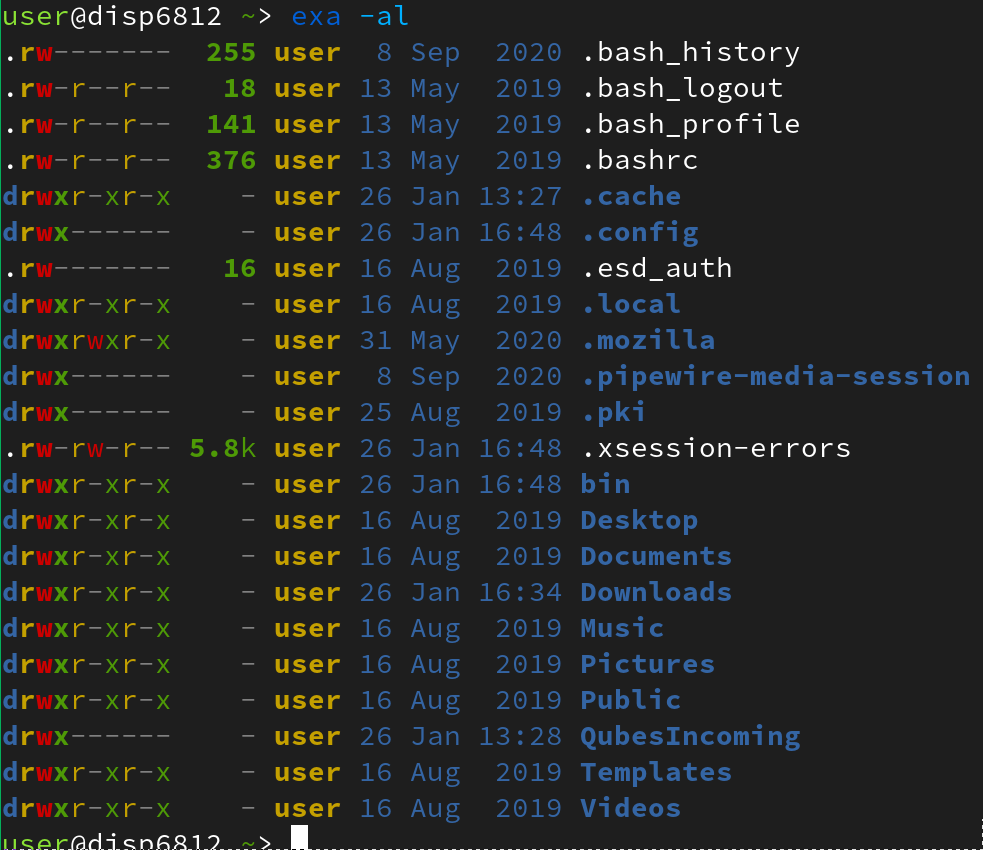

It contains “dot-files” or hidden files, with a ‘.’ in front of their

filenames.

These often contain configuration particular to a user.

~/.config/ for example, is a folder of configuration files

for the various applications you have run.

Demonstrate in parallel:

GUI file browser:

thunar

Terminal commands:

ls

tree

ranger

mc

All these display and manage the same file system,

the back-end structure of files and directories.

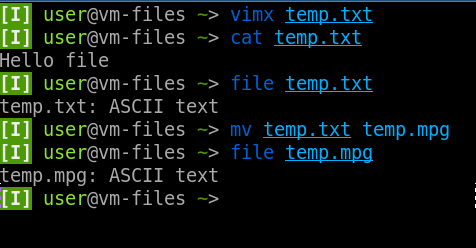

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Everything_is_a_file

How do you use the operating system to access it’s files,

its programs (which are files),

and it’s devices (which “are” files)?

Linux does not care what file extension you use,

but instead looks at the contents of the files.

As a child, one starts reading with picture books.

As an adult, using written language,

efficient expressiveness has virtually no limit in the degree to which

you can re-combine ideas.

Natural language literacy results in an explosion of the ability to

express oneself in ever-nuanced detail.

As a child, one starts using a computer by clicking on

pictures.

As an adult, using written commands,

efficient expressiveness has virtually no limit in the degree to which

you can re-combine functions.

Command literacy results in an explosion of the ability to express

modular elemental commands in ever-nuanced detail.

It is time to grow up and learn to read and write…

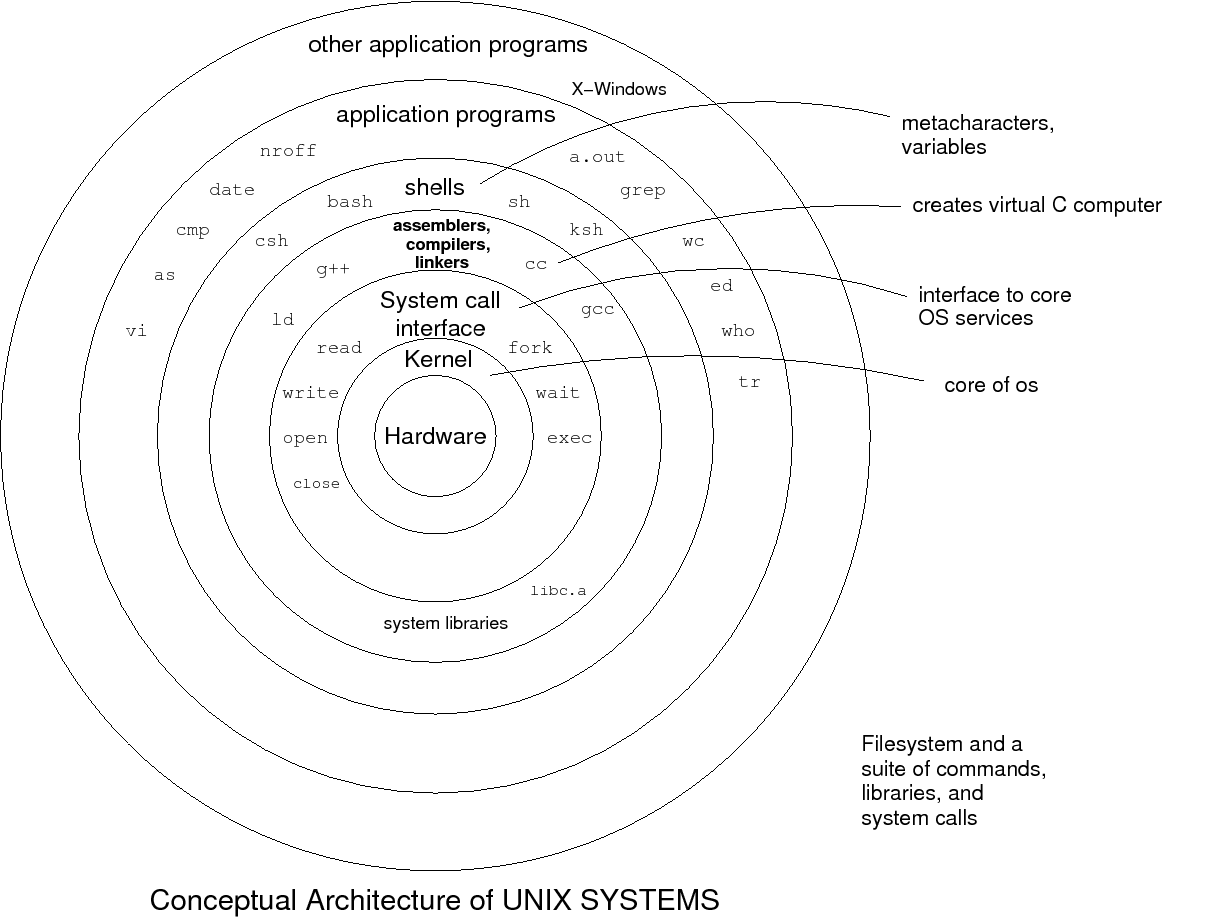

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shell_(computing)

Operating system shells are a command-line interface (CLI).

In computing, a shell is a user interface,

that provides access to an operating system’s services.

A shell is also an interpreted, interactive, programming language (a

scripting language).

What is a shell?

login is a program that logs users in to a

computer.

When it logs you in, login checks a file called

/etc/passwd to see which shell you use.

After it authenticates you, it runs whatever your shell happens to

be.

Shells give you a way to run programs and view their output.

Shells also usually include some built-in commands.

Shells use variables to track information about commands and the system

environment.

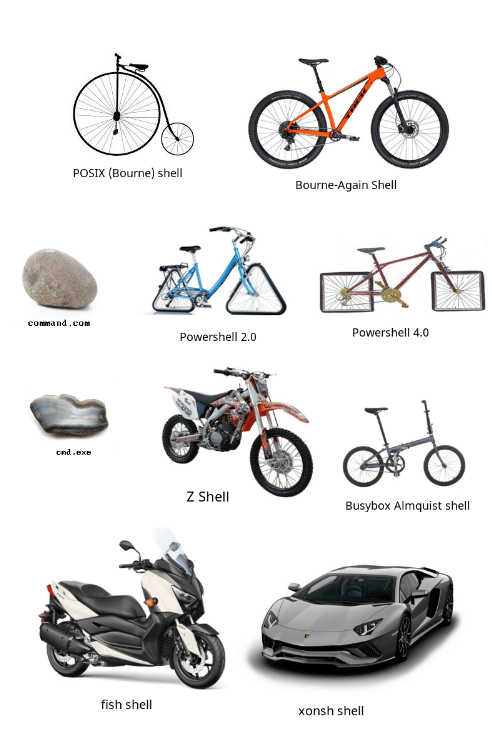

The standard interactive shell is bash.

There are others, for example, zsh or

fish.

It is named a shell because it is like an outermost layer,

around the operating system kernel.

There are many shells, and bash is just one:

https://medium.com/better-programming/fish-vs-zsh-vs-bash-reasons-why-you-need-to-switch-to-fish-4e63a66687eb

https://medium.com/almoullim/from-bash-to-zsh-to-fish-e432f1e1b9f8

https://zellwk.com/blog/bash-zsh-fish/

https://www.davidokwii.com/bash-zsh-and-fish-the-awesomeness-of-linux-shells/

https://medium.com/better-programming/why-i-use-fish-shell-over-bash-and-zsh-407d23293839

https://www.skepticism.us/posts/2017/10/time-to-pick-a-new-shell/

and others too…

https://xon.sh

The fancy car above is a python super-set…

containing all python and a lot of bash.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?reload=9&v=uaje5I22kgE&feature=youtu.be

See the shells on your system:

cat /etc/shells

Results in this on my system:

/bin/sh

/bin/bash

/usr/bin/sh

/usr/bin/bash

/usr/bin/zsh

/bin/zsh

/usr/bin/tmux

/bin/tmux

/usr/bin/fish

/bin/fish

/usr/bin/xonsh

/bin/xonsh

Most shells use std-io strings as the mechanism of trading data between two processes.

However, some new, innovative shells exist,

which actually trade structured string data,

whether that be json, tables, or similar,

between procesess:

https://www.nushell.sh/ (very cool!)

https://www.nushell.sh/book/quick_tour.html

For example, rather than pipe raw data between processes,

pipe structured data like json:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/JSON

For example, some json data including lists and dictionaries:

{

"first_name": "John",

"last_name": "Smith",

"is_alive": true,

"age": 27,

"address": {

"street_address": "21 2nd Street",

"city": "New York",

"state": "NY",

"postal_code": "10021-3100"

},

"phone_numbers": [

{

"type": "home",

"number": "212 555-1234"

},

{

"type": "office",

"number": "646 555-4567"

}

],

"children": [

"Catherine",

"Thomas",

"Trevor"

],

"spouse": null

}This is similar to a funny little project,

implementing basic data structures in bash/python:

https://gitlab.com/behindthebrain/datashell

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shebang_%28Unix%29

See this file’s shebang:

LinuxBash/LearnBash.sh

Bash is standard.

Some other shells like fish are nice, and those like nushell are

innovative.

All bash code for my classes must be auto-formatted by

shfmt with the following arguments.

Pre-check and fix warnings where needed:

$ shellcheck yourscript.sh

Pre-format

$ shfmt -i 4 yourscript.sh

Run code as:

$ bash yourscript.sh

without the need for a shebang, or

$ . yourscript.sh

or

$ ./yourscript.sh

where this is at the top of your file:

#!/bin/bash

actually specifies un-ambiguously the use of bash, and the binary

location. This is the one you should use.

#!/usr/bin/env bash

specifies ambiguously the use of bash, but not the binary location, thus

opening a security vulnerability; env was not intended for

this purpose, and it’s use here comes with a number of concrete

disadvantages.

#!/bin/sh

is the system’s default shell, and is ambiguous. This is like saying (by

analogy), I scripted this, maybe in python2, maybe python3, or maybe

even perl…and you’re supposed to guess blindly. It sometimes means a

POSIX compatible shell, but not always.

Debug your code:

bash -x yourscript.sh args if any

or

bashdb yourscript.sh args if any

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bash_(Unix_shell)

Bash is a shell, a command processor that typically runs in a text

window,

where the user types commands that cause actions.

Bash can also read and execute commands from a file,

called a “shell script” or “bash script”.

Bash is the most common shell;

it is the default go-to.

Demonstrate:

ssh into campus machine.

Navigate around.

Create a directory.

Make a bash script.

Run it.

Make sure you understand the command; it could be dangerous.

$ at the beginning of a line is NOT part of the

command.

$ in the middle of the command is part of the

command…

It’s possible to hide nasty commands in “invisible” white-space

characters,

so you may want to manually re-type commands you’re copying…

Navigating the file-system

$ ls List files in the

current directory. You can alternatively give it a directory to

list.

$ ls -l Display the output in a detailed

list, one line per file.

$ ls -h Display file sizes in a

human-readable format.

$ ls -a Display all files, including

hidden ones.

$ pwd Print working

directory. This is where you are now!

$ cd DIRECTORY Change

directory.

$ cd without a directory takes you $HOME, as

does cd ~ or cd $HOME

$ cd - takes you to the previous directory you were

in

$ cd .. takes you up/back a directory in the tree

$ cd ../../ you up/back two levels in the directory

tree

$ tree prints an enumerated walk through all

sub-directories of your current working director, or the directory

passed to it.

Note:

exa is a nicer replacement for ls and tree,

written in the Rust programming language

(an actually well-designed language).

$ exa -l

$ exa --tree

File and Directory Shortcuts:

. always refers to the directory you are currently

in.

.. always refers to the parent of the current

directory.

~ refers to your home directory.

/ refers to the root directory. Everything lives under

root.

For vim-like shortcuts at the interactive bash terminal:

(echo "set -o vi" >>~/.bashrc)

Searching for partial matches

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wildcard_character

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glob_%28programming%29

* matches 0 or more characters in a file or directory

name.

? matches exactly one character in a file or directory

name.

For example, $ ls *.cpp lists all your cpp files.

$ mv SOURCE DESTINATION

Move (or rename) files.

$ mv -i Interactively ask you before

overwriting files.

$ mv -n Never overwrite files.

mv is used to rename;

just move the file to the same directory with a different name,

for example:

$ mv old_name new_name

$ cp SOURCE DESTINATION

Copy files.

$ cp -r Recursively copy directories,

which is what you want to do.

$ rm FILE Remove one

or more files.

$ rm -f Forcibly remove nonexistent

files.

$ rm -r DIRECTORY removes a directory and all it’s

files

$ mkdir DIRECTORY

Makes a

directory.

$ mkdir -p DIRECTORY/SUBDIRECTORY Makes every missing

directory in the given path

$ rmdir DIRECTORY

Removes a directory,

when it’s empty anyway.

$ cat [FILE] Print out file contents.

$ less [FILE] Paginate files or STDIN.

$ head [FILE] Print lines from the top of a file or

STDIN.

$ tail [FILE] Print lines from the end of a file or

STDIN.

$ tail -n LINES Print LINES lines instead of 10.

$ tail -f Print new lines as they are appended

($ tail only).

$ sort [FILE] Sorts files or

STDIN.

$ sort -u Only prints one of each matching line

(unique).

Often paired with $ uniq for similar effect.

$ diff FILE1 FILE2 Shows differences

between files.

a/d/c reports Added/Deleted/Changed.

$ diff --side-by-side FILE1 FILE2 may be easier to read

+++++++++++++++++

Cahoot-02b.1

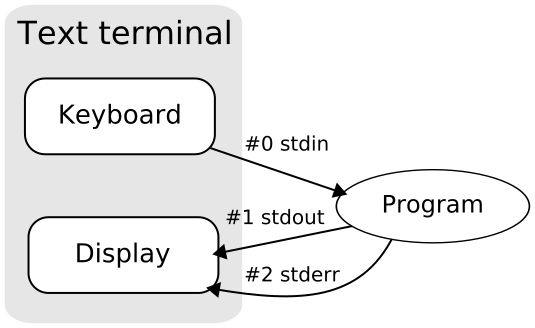

For more detail on this section, see:

../../ComputationalThinking/Content/InputOutput.html

In general, a command (a program):

Gets data to process from standard input or stdin (default:

keyboard).

Returns processed data to standard output or stdout (default:

screen).

If program execution causes errors,

error messages are sent to standard error or stderr (default:

screen).

Those three inputs and outputs are files, and are always open.

As all open files, they are assigned to a file descriptor (an

integer).

File descriptors for stdin, stdout and stderr:

| File | File descriptor |

|---|---|

| /dev/stdin or /dev/fd/0 | 0 |

| /dev/stdout or /dev/fd/1 | 1 |

| /dev/stderr or /dev/fd/2 | 2 |

Each program has three default I/O streams:

STDIN: input, by default from the keyboard (std::cin

/ input()).

STDOUT: output, by default to the screen (std::cout /

print()).

STDERR: output, by default to the screen

(std::cerr).

We can redirect IO to, or from, files or other programs.

$ cmd1 | cmd2 Pipe STDOUT from cmd1 into STDIN

for cmd2.

$ cmd <input.txt Funnel data from input.txt

to STDIN for cmd.

$ cmd >output.txt Funnel STDOUT from cmd

into output.txt.

Question: what do you think the following does?

$ cmd <input.txt >output.txt

bash uses 1 and 2 to refer to

STDOUT and STDERR.

$ cmd 2> err.txt Funnel STDERR from cmd

into err.txt.

$ cmd 2>&1 Funnel STDERR from cmd into

STDOUT.

$ cmd &> all-output.txt Funnel all output from

cmd into all-output.txt.

Common usage: $ cmd &>/dev/null dumps all output to

the bit bucket.

Shells keep track of a lot of information in variables.

$ printenv shows all the environment variables set in your

shell

$ env shows exported environment variables

(variables that are also set in the environment of programs launched

from this shell).

$ set lets you set them.

$ VAR="value" sets the value of $VAR. (No

spaces around the =!).

$ echo $VAR prints the value of a variable in the

shell.

You can get environment variable values in C++ with getenv().

$PATH Colon-delimited list of directories to look for

programs in.

$EDITOR Tells which editor you would prefer programs to

launch for you.

$ ~/.bashrc runs every time you start bash, so

you can export customization commands there.

Tab completion works for files and commands!!!

When it doubt, tap tab twice!!

History:

up/down arrows scroll through history.

ctrl-r searches backwards through history.

$ !! holds the last command executed.

$ !$ holds the last argument to the last command.

$ $? holds the return/exit code from the last command

$ alias l=ls runs ls when you type

l

The effect of this variable is temporary.

but, you can put this in a bash startup script.

$ ps Process

list.

$ ps aux or $ ps -ef show lots of information

about all processes.

$ ps has crazy whack options.

$ top and $ htop give an interactive

process listing.

Start processes in the background:

$ command &.

If you have a command running in the foreground, you can stop it with

ctrl-z.

$ fg starts the last process in the foreground.

$ bg starts the last process in the background.

$ disown enables you to close the terminal, but leave the

job going.

$ jobs shows your running jobs.

$ fg %2 starts job 2 in the foreground.

$ kill PID Kills a process. (You can do

$ kill %1!)

$ killall command Kills every process running

command.

Last but not least: –help, -h, and man

$ COMMAND --help or $ COMMAND -h often

provide concise help

$ man COMMAND opens a full manual listing for that

command.

$ info COMMAND for some other types of command

q quits the manual.

j/k scroll up and down a line.

space scrolls down one page.

/thing searches within a man page,

with syntax like how less, more, and

vim search for things.

n/N go to next/previous search result.

$ man man gives you the manual for the manual!

$ man -k "KEYWORD" searches all the man pages for

thing.

$ help COMMAND gives you help with builtins.

+++++++++++++++++

Cahoot-02b.2

Read this tutorial in full!

http://linuxcommand.org/lc3_learning_the_shell.php

This part is for those who already know a bit of programming

(CS1500 can skim or skip this section).

LinuxBash/hello.sh

Shell scripts are the duct tape and bailing wire of computer programming:

Automate repeated tasks.

Great for jobs that require a lot of interaction with files.

To set up the environment for big, complicated programs.

To make sure you can reproduce installing or running larger more

complicated programs.

When you need to stick a bunch of programs together into something

useful.

To add customizations to your environment.

$ read variable lets the user enter input into

variable.

$ echo "string" prints string to the screen.

$ echo $variable prints variable’s contents to the

screen.

Example

LinuxBash/inout.sh

A practical example

LinuxBash/runit1.sh

The following are special variables,

automatically available to any bash script when it it run:

$? Exit code of the last command run.

$0 Name of command that started this script (almost always

the script’s name).

$1, $2, …, $9 Command line arguments 1-9.

$@ All command line arguments except $0.

$# The number of command line arguments in

$@.

Bash really likes splitting things up into words.

$ for arg in $@ will NOT do what you want.

$ for arg in "$@" correctly handles args with spaces.

In general, when using the value of a variable you don’t control,

it is wise to put ” around that variable.

Quoting like “\(thing" makes things

inside more literally interpreted,

and quoting like '\)thing’ makes them even more literal.

A Spiffier Example

LinuxBash/runit2.sh

In a bash script, or one-line bash command, branching is

possible:

LinuxBash/if.sh

[ ] is shorthand for the $ test

command.

[[]] is a bash keyword which has extra fancy

features

[ ] works on most shells, but [[]] is more

modern.

(( )) is another bash keyword. It does

arithmetic.

=, == String equality OR pattern matching if the RHS is

a pattern.

!= String inequality.

< The LHS sorts before the RHS.

> The LHS sorts after the RHS.

-z The string is empty (length is

zero).

-n The string is not empty

(e.g. $ [ -n "$var" ]( -n "$var" )).

-eq Numeric equality

(e.g. $ [ 5 -eq 5 ]( 5 -eq 5 )).

-ne Numeric inequality.

-lt Less than

-gt Greater than

-le Less than or equal to

-ge Greater than or equal to

-e True if the file exists

(e.g. $ [ -e story.txt ]( -e story.txt ))

-f True if the file is a regular file

-d True if the file is a directory

There are a lot more file operators that deal with even fancier

stuff.

&& Logical AND

|| Logical OR

! Logical NOT

You can use parentheses to group statements too.

This mostly works just like C++ arithmetic.

You don’t need $ on the front of normal variables:

(( number_variable = number_variable + 4 ))

** does exponentiation.

You can do ternaries:

(( 3 < 5 ? 3 : 5 ))

http://www.gnu.org/software/bash/manual/bash.html#Shell-Arithmetic

You can capture the output of math into a variable like this:

arr=$(( 3 + 5 ))

LinuxBash/runit3.sh

(Could you spiff it up even more with file checks?)

Meh, if you use these:

LinuxBash/case.sh

LinuxBash/for.sh

LinuxBash/args.sh

Can return a small number (but that’s it).

Returning is intended for exit/return codes, not data/content.

* [ ] Add example about returning a number from functions.

To return more than just a small number, you need to capture the output

of the command:

To get data back from a function

LinuxBash/arrays.sh

LinuxBash/arrfunc.sh

LinuxBash/assoc_arr.sh

Escaping characters: use \ on \,, $, “, ’,

#`.

$ pushd and $ popd create a stack of

directories.

Use these instead of $ cd.

$ dirs lists the stack.

$ set -u gives an error if you try to use an unset

variable.

$ set -x prints out commands as they are run.

$ : is a no-op command, like pass.

A double dash (--) is used in most bash built-in

commands,

and many other commands,

to signify the end of command options,

after which only positional parameters are accepted.

Example use:

Lets say you want to grep a file for the string -v ,

- normally -v will be considered the option to

reverse the matching meaning

(only show lines that do not match),

but with -- you can grep for string -v like

this:

grep -- -v file.

grep -e -v will also work.

#!/bin/bash

# bash generate random alphanumeric string

< /dev/urandom tr -cd "[:print:]" | head -c 32; echo

< /dev/urandom tr -cd '[:graph:]'| tr -d '\\' | head -c 32; echo

# if you dont want ` characters in generated string.

# h` because is an escape character in many languages causes problems

LC_ALL=C tr -dc 'A-Za-z0-9!"#$%&'\''()*+,-./:;<=>?@[\]^_`{|}~' </dev/urandom | head -c 13 ; echo

# bash generate random 32 character alphanumeric string (upper and lowercase) and

NEW_UUID=$(cat /dev/urandom | tr -dc 'a-zA-Z0-9' | fold -w 32 | head -n 1)

# bash generate random 32 character alphanumeric string (lowercase only)

cat /dev/urandom | tr -dc 'a-zA-Z0-9' | fold -w 32 | head -n 1

# Random numbers in a range, more randomly distributed than $RANDOM which is not

# very random in terms of distribution of numbers.

# bash generate random number between 0 and 9

cat /dev/urandom | tr -dc '0-9' | fold -w 256 | head -n 1 | head --bytes 1

# bash generate random number between 0 and 99

NUMBER=$(cat /dev/urandom | tr -dc '0-9' | fold -w 256 | head -n 1 | sed -e 's/^0*//' | head --bytes 2)

if [ "$NUMBER" == "" ]; then

NUMBER=0

fi

# bash generate random number between 0 and 999

NUMBER=$(cat /dev/urandom | tr -dc '0-9' | fold -w 256 | head -n 1 | sed -e 's/^0*//' | head --bytes 3)

if [ "$NUMBER" == "" ]; then

NUMBER=0

fiHow to debug your bash scripts:

$ bash -x script.sh

In your script file itself:

set -x

..code to debug...

set +xhttp://bashdb.sourceforge.net/

Pretty decent

Just a simple syntax checker

http://shellcheck.net

$ shellcheck myscript.sh

https://github.com/ryakad/bashdb

"$thing" is usually a good idea, even

when it may be optional

If we set

a=apple # a simple variable

arr=(apple) # an indexed array with a single elementand then echo the expression in the second column,

we would get the result / behavior shown in the third column.

The fourth column explains the behavior:

# Expression Result Comments

1 "$a" apple variables are expanded inside ""

2 '$a' $a variables are not expanded inside ''

3 "'$a'" 'apple' '' has no special meaning inside ""

4 '"$a"' "$a" "" is treated literally inside ''

5 '\` invalid can not escape a ' within `; use "'" or $'\'' (ANSI-C quoting)

6 "red$arocks" red $arocks does not expand $a; use ${a}rocks to preserve $a

7 "redapple$" redapple$ $ followed by no variable name evaluates to $

8 '\"' \" \ has no special meaning inside ''

9 "\'" \' \' is interpreted inside "" but has no significance for '

10 "\"" " \" is interpreted inside ""

11 "*" * glob does not work inside "" or ''

12 "\t\n" \t\n \t and \n have no special meaning inside "" or ''; use ANSI-C quoting

13 "`echo hi`" hi `` and $() are evaluated inside "" (backquotes are retained in actual output)

14 '`echo hi`' echo hi `` and $() are not evaluated inside '' (backquotes are retained in actual output)

15 '${arr[0]}' ${arr[0]} array access not possible inside ''

16 "${arr[0]}" apple array access works inside ""

17 $'$a\'' $a' single quotes can be escaped inside ANSI-C quoting

18 "$'\t'" $'\t' ANSI-C quoting is not interpreted inside ""

19 '!cmd' !cmd history expansion character '!' is ignored inside ''

20 "!cmd" cmd args expands to the most recent command matching "cmd"

21 $'!cmd' !cmd history expansion character '!' is ignored inside ANSI-C quoteshttps://wiki.bash-hackers.org/syntax/quoting

docopt bash

https://bashly.dannyb.co/

../../ComputationalThinking/Content/EvilEval.html

``

$()

* [ ] todo

LinuxBash/LearnBash.sh (giant

bash script to learn bash)

tools-for-computer-scientists.pdf

Appendix E, Chapter 1

LinuxBash/02-shell_commands.pdf

(my old slides)

LinuxBash/04-shell_scripting.pdf

(my old slides)

In alphabetical order:

http://labor-liber.org/en/gnu-linux/introduction/

(decent high level summary)

http://linuxcommand.org/lc3_learning_the_shell.php

(great starting point, read this)

http://linuxcommand.org/lc3_writing_shell_scripts.php

http://linuxcommand.org/tlcl.php

LinuxBash/TLCL-24.11.pdf

http://mywiki.wooledge.org/BashGuide

http://mywiki.wooledge.org/Bashism (bash versus

posix/dash/sh)

http://mywiki.wooledge.org/BashProgramming

http://tille.garrels.be/training/bash

http://wiki.bash-hackers.org/

http://www.bash.academy/ (good bash-purist tutorial;

un-finished for advanced topics)

http://www.linfo.org/pipe.html

http://www.panix.com/~elflord/unix/bash-tute.html

https://arachnoid.com/linux/shell_programming.html

https://bash.awesome-programming.com/

https://devhints.io/bash (cheat sheet)

https://doc.opensuse.org/documentation/leap/startup/single-html/book.opensuse.startup/index.html#part.bash

https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Bash_Shell_Scripting

https://fedoramagazine.org/bash-shell-scripting-for-beginners-part-1/

https://github.com/awesome-lists/awesome-bash

https://github.com/dylanaraps/pure-bash-bible

https://github.com/jlevy/the-art-of-command-line

https://learnxinyminutes.com/docs/bash/ (good, read

this!)

<https://lym.readthedocs.io/en/latest/index.html

https://ryanstutorials.net/bash-scripting-tutorial/

(good intro for beginners)

https://swcarpentry.github.io/shell-extras/

https://swcarpentry.github.io/shell-novice

https://tldp.org/HOWTO/Bash-Prog-Intro-HOWTO.html

https://tldp.org/LDP/abs/html/

https://tldp.org/LDP/Bash-Beginners-Guide/html/

https://www.gnu.org/software/bash/manual/ (THE bash

manual)

https://www.quora.com/What-are-some-good-books-for-learning-Linux-bash-or-shell-scripting

(list of more)

https://www.quora.com/What-is-the-best-resource-for-learning-Bash-scripting

(list of more)

https://www.shellscript.sh/ (ok)

https://www.tutorialspoint.com/unix/ (mediocre, decent

overview, some mistakes)

https://gitlab.com/slackermedia/bashcrawl (decent,

basic)

https://overthewire.org/wargames/ (pretty good, a little

more advanced)

https://www.redhat.com/en/command-line-heroes/bash/index.html?extIdCarryOver=true&sc_cid=701f2000001OH79AAG

(mediocre?)

Next: VersionControl.html