https://www.xkcd.com/1739/

Show self-recording screencast to start.

Lecture start/end points are noted below in the notes.

* Lecture 1: https://vimeo.com/521071999

* Lecture 2: https://vimeo.com/522062744

* Tip: If anyone want to speed up the lecture videos a little, inspect

the page, go to the browser console, and paste this in:

document.querySelector('video').playbackRate = 1.2

https://realpython.com/python-thinking-recursively/

https://www.python-course.eu/python3_recursive_functions.php

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Recursion

As with any constructive discussion, we start with definitions:

“To understand recursion, you must understand

recursion.”

What is base case above?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Recursive_acronym

GNU: GNU’s Not Unix

YAML: YAML Ain’t Markup Language (initially “Yet Another Markup

Language”)

WINE: WINE Is Not an Emulator

https://www.google.com/search?&q=recursion (notice

the: “Did you mean recursion?”)

The first line of these definitions may seem circularly

dissatisfying.

It is the second line that grounds these definitions, making them

useful.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natural_number

For example, 1, 2, 3, 4, …

Natural numbers are either:

n + 1, where n is a natural number, or

1

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exponentiation

For example, 28 = 256

Exponentiation:

bn = b * bn-1, or

b0 = 1

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Factorial

For example,

5! = 5 × 4 × 3 × 2 × 1 = 120

Factorial:

n! = n * ((n - 1)!), or

0! = 1

Recursion in computer science is a self-referential

programming paradigm,

as opposed to iteration with a while() or for() loop, for

example.

Concretely, recursion is a process in which a function calls

itself.

Often the solution to a problem can employ solutions to smaller

instances of the same problem.

You’re not just decomposing it into parts, but incrementally smaller

parts.

Condition or test, often an if(), which tests for a

base case (which often results in

termination),

which only executes once, after doing the

recursive case repeatedly.

Recall that \((a * b)^x = a^x * b^x\)

In Python:

Recursion/python/recursion_00_exp.py

#!/usr/bin/python3

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

"""

Exponentiation

"""

print(2**8)

# %% Loop

def exp_loop(b: int, n: int) -> int:

result = 1

for c in range(n):

result *= b

print("c=", c, "and result=", result)

return result

for n in range(1, 17):

val = exp_loop(2, n)

print("2 to the ", n, "is ", val, "\n")

# %% What is the b^-n?

def exp_loop_neg_rec(b: int, n: int) -> float:

result = 1

if 0 <= n:

for c in range(n):

result *= b

print("c=", c, "and result=", result)

return result

else:

return 1 / exp_loop_neg_rec(b, -n)

for n in range(-1, -17, -1):

val_float = exp_loop_neg_rec(2, n)

print("2 to the ", n, "is ", val_float, "\n")

# %% Inefficient recursive exponentiation

def exp_rec(b: int, n: int) -> int:

"""

Calculates b^n for positive n integers

"""

print("Calling with b =", b, "and n=", n)

if n == 0:

return 1

else:

return b * exp_rec(b, n - 1)

for n in range(1, 17):

val = exp_rec(2, n)

print("2 to the ", n, "is ", val, "\n")

# %% Efficient recursive exponentiation

def exp_rec_eff(b: int, n: int) -> int:

"""

Efficiently calculates b^n for positive n integers

"""

print("Calling with b =", b, "and n=", n)

if n == 1:

return b

elif (n & 1) == 0:

return exp_rec_eff(b * b, n // 2)

else:

return exp_rec_eff(b * b, n // 2) * b

for n in range(1, 17):

val = exp_rec_eff(2, n)

print("2 to the ", n, "is ", val, "\n")In C++

Recursion/cpp/Recursion00Exp.cpp

/**

Functions to take exponents: b^n

Note: ^ is not c++ syntax for exponentiation.

**/

#include <iostream>

#include <exception>

using namespace std;

// With a loop, accumulating up

double simpleExpLoopPart(int b, int n) {

double result = 1;

for (int c = 1; c <= n; c++) {

result *= b;

cout << "c = " << c << ", and result = " << result << endl;

}

return result;

}; // what will happen if we enter a negative number? What about 0?

// With a loop and one-layer recursion for negatives

double simpleExpLoop(int b, int n) {

double result = 1;

if (n >= 0) {

for (int c = 1; c <= n; c++) {

result *= b;

cout << "c = " << c << ", and result = " << result << endl;

}

} else {

return 1 / simpleExpLoop(b, -n);

}

return result;

};

// Fully recursively no negatives

double simpleExpRecurPart(int b, int n) {

cout << "Calling simpleExpRecurPart with b = " << b << " and n = " << n

<< endl;

if (n == 0) {

return 1;

} else {

return b * simpleExpRecurPart(b, n - 1);

}

// can have return statements above or 1 here

} // what will happen if we enter a negative number?

// Fully ecursively:

double simpleExpRecur(int b, int n) {

double result = 1;

cout << "Calling simpleExpRecur with b = " << b << " and n = " << n << endl;

if (n == 0) {

return 1;

} else if (n > 0) {

return b * simpleExpRecur(b, n - 1);

} else {

return 1 / simpleExpRecur(b, -n);

}

// can have return statements above or 1 here

}

// Fast exponentiation (skipped 0^neg and negative special conditions here)

long long expEff(const long long b, const int n) {

cout << "Calling expEff with b = " << b << " and n = " << n << endl;

if (n == 1) {

// this is a faster alternative to base case n==0 above, how much?

return b;

} else if ((n & 1) == 0) {

// bitwise faster than modulus to check even here

return expEff(b * b, n / 2);

} else {

// odd

return expEff(b * b, n / 2) * b;

}

// can have return statements above or 1 here

}

int main() {

int b = 2;

int n = 40;

cout << "simpleExpLoopPart: " << simpleExpLoopPart(b, n) << endl << endl;

cout << "simpleExpLoop: " << simpleExpLoop(b, n) << endl << endl;

cout << "simpleExpRecurPart: " << simpleExpRecurPart(b, n) << endl << endl;

cout << "simpleExpRecur: " << simpleExpRecur(b, n) << endl << endl;

cout << "expEff: " << expEff(b, n) << endl << endl;

return 0;

}In Haskell

AlgorithmsSoftware/AlgExp.hs

#!/usr/bin/runghc

module AlgExp where

import Data.Bits

-- |

-- >>> expFun 2 3

-- 8

expFun :: Integer -> Int -> Integer

expFun b n = product (replicate n b)

-- |

-- >>> expRec 2 3

-- 8 % 1

expRec :: Rational -> Integer -> Rational

expRec b n

| n == 0 = 1

| 0 < n = b * expRec b (n - 1)

| otherwise = 1 / expRec b (-n)

-- |

-- >>> expEff 2 3

-- 8

expEff :: Integer -> Integer -> Integer

expEff b n

| n == 1 = b

| n .&. 1 == 0 = expEff (b * b) (div n 2)

| otherwise = b * expEff (b * b) (div n 2)

main :: IO ()

main = do

print (expRec 2 3)

print (expFun 2 3)

print (expEff 2 3)Check out code now!

We can use an accumulator variable, starting at low values, working our

way up.

What is the big theta of this function?

What is the number of iterations for for n = 1, n = 2, n = 3?

++++++++++++++++++

Cahoot-14.1

Ask: What is 2-8?

Check out code now!

We use a trivial one-layer recursion.

A recursive call is like regular function calls!

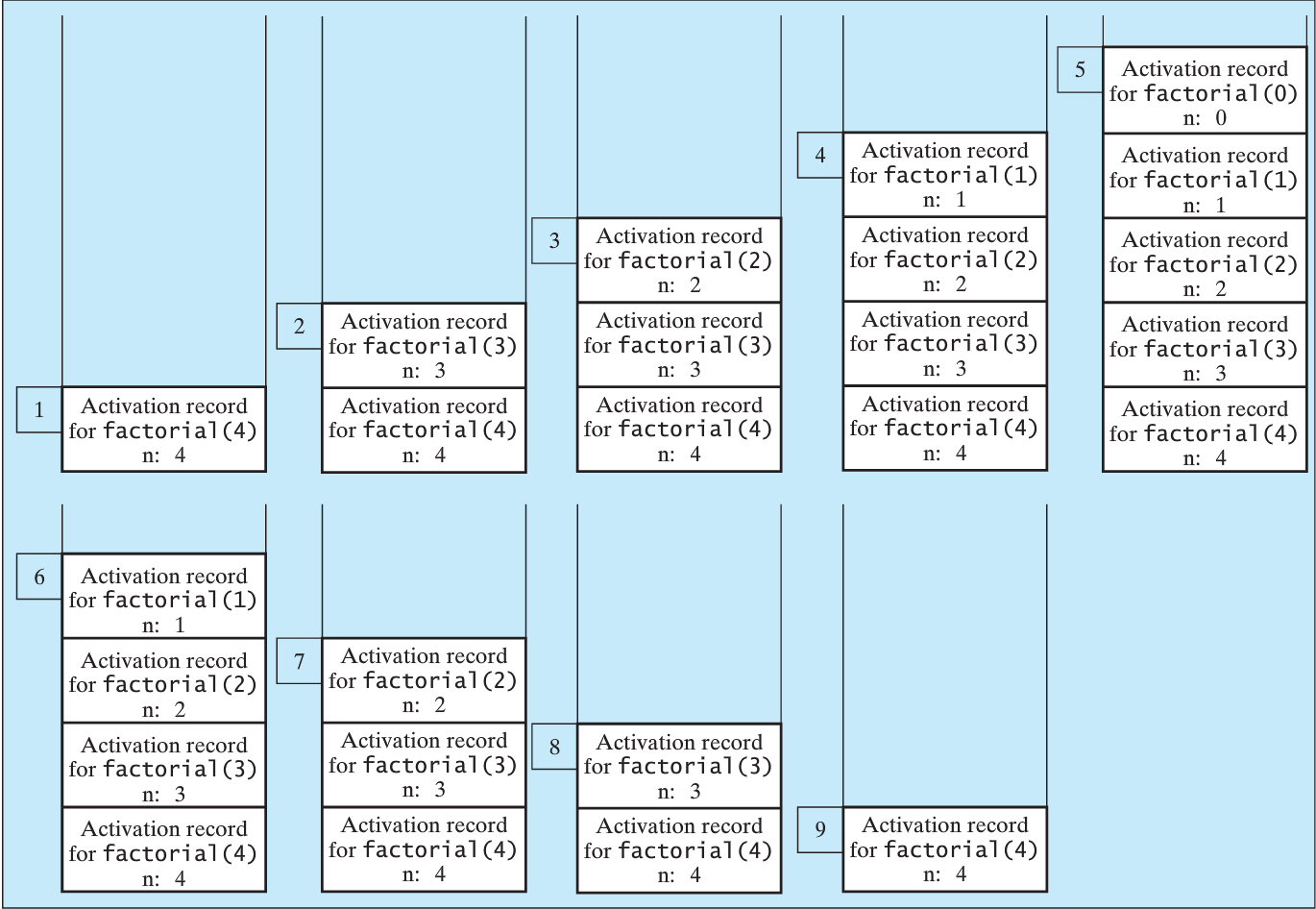

How many activation records exist on the stack?

Show the stack in the debugger.

The recursive case looks just like your mathematical definition.

Recursive case:

bn = b * bn-1

Base case (termination):

b0 = 1

(or slightly faster: b1 = b)

Condition/test, which checks for the base:

if(n == 0):

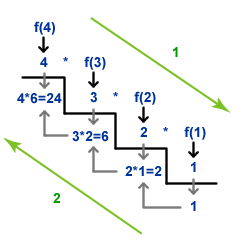

For example:

b4 =

b * b3 =

b * (b * b2) =

b * (b * (b * b1)) =

b * (b * (b * (b * b0)))

When does the first function call actually finish?

Actually trace code now!

Unlike the iterative algorithm, which accumulates a value up, recursion

starts at the top values, and works down.

In the debugger, watch the activation records on the stack, count them

as we trace.

What is the big theta of this function?

Recursion depth for n = 1, n = 2, n = 3?

Real-world example:

This algorithm is used to generate cryptographic RSA keys.

Exponentiation is used very frequently in big-cryptography.

Imagine you have a web-server that makes 1 million connections a

day.

Some bitcoin server farms have power bills in the many millions per

month!!

How many dollars in power bills, or carbon dioxide production could you

save,

with just an improvement from an improvement from a big theta of n to

log2(n)??

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exponentiation_by_squaring

Recall that \((a * b)^x = a^x * b^x\)

To obtain bn, do recursively:

if n is even,

do b^(n//2) * b^(n//2)

if n is odd,

do b * b^(n//2) * b^(n//2)

with base case

b1 = bNote:

n//2 is integer division (floor)

What is b62 ?

b62 = (b31)2

b31 = b(b15)2

b15 = b(b7)2

b7 = b(b3)2

b3 = b(b1)2

b1 = b

What is b61 ?

b61 = b(b30)2

b30 = (b15)2

b15 = b(b7)2

b7 = b(b3)2

b3 = b(b1)2

b1 = b

How many multiplications when counting from the bottom up?

Check out the code now.

What is the maximum number of activation records on the stack for a

given n?

Display the printed output to show how many fewer multiplications there

are!

++++++++++++++++++

Cahoot-14.2

Paying attention to order of code around recursive calls is important!!

Functions call themselves.

Instructions placed before the recursive call are executed once per

recursion,

before the next call, “on the way down the stack”.

Instructions placed after the recursive call are executed

repeatedly,

after the maximum recursion has been reached, “on the way up the

stack”.

Python code:

Recursion/python/recursion_01_order.py

#!/usr/bin/python3

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

"""

Order of statements in the stack matters.

Note, this string defaulted-tab trick is handy!

This program counts from 4, with tabs

"""

def order_matters(n: int, indent: str = " ") -> None:

print("\n", indent, " Next call starts here", sep="")

print(indent, "Before the recursive call, n is", n)

if n > 0:

print(indent, "calling with ", n + 1)

order_matters(n - 1, indent + " ")

print(indent, "After the recursive call, n is ", n, "\n")

print(indent, "Function call ends here")

order_matters(4)C++ code:

Recursion/cpp/Recursion01OrderMatters.cpp

/**

Illustrates printing before and after a recursive call.

**/

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void orderMatters(int c, string indent = "") {

cout << indent << "c before the recursive statement: " << c << endl;

if (c > 0) {

orderMatters(c - 1, indent += " ");

}

// This statement will not show up if you returned countdown's value

cout << indent << "c after the recursive statement: " << c << endl;

}

int main() {

orderMatters(4);

return 0;

}C++ code:

Recursion/cpp/Recursion01Stars.cpp

/**

Become a recursion superstar...

**/

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void stars(int n, string indent = "") {

cout << indent << " Before with n=" << n << endl;

if (n > 1) {

stars(n - 1, indent += "*");

cout << indent << " After with n=" << n << endl;

}

return;

}

void starsPlus(int n, string indent = "") {

cout << indent << " Before with n=" << n << endl;

if (n > 1) {

stars(n - 1, indent + "*");

cout << indent << " After with n=" << n << endl;

}

return;

}

int main() {

int n;

cout << "Enter a depth: ";

cin >> n;

stars(n);

cout << endl << endl;

starsPlus(n);

return 0;

}Haskell code:

Recursion/haskell/Recursion01OrderMatters.hs

#!/usr/bin/runghc

module Recursion01OrderMatters where

orderMatters :: Int -> String -> String

orderMatters n indent =

if n > 0

then show n ++ indent ++ "before\n" ++ orderMatters (n - 1) (indent ++ " ") ++ show n ++ indent ++ "after\n"

else ""

main :: IO ()

main = do

putStrLn (orderMatters 4 " ")Stack of what?

Check out the stack in pudb, gdb,

ghci.

The state of execution when you call a new function is still waiting

when you get back to it!

These are different concepts:

If your function runs in factorial time, that is bad.

But computing factorial itself is not too slow.

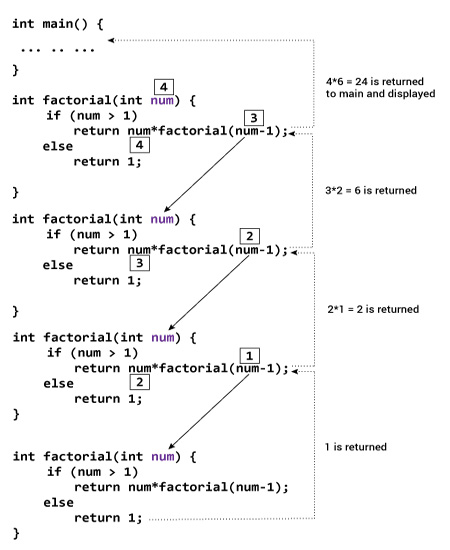

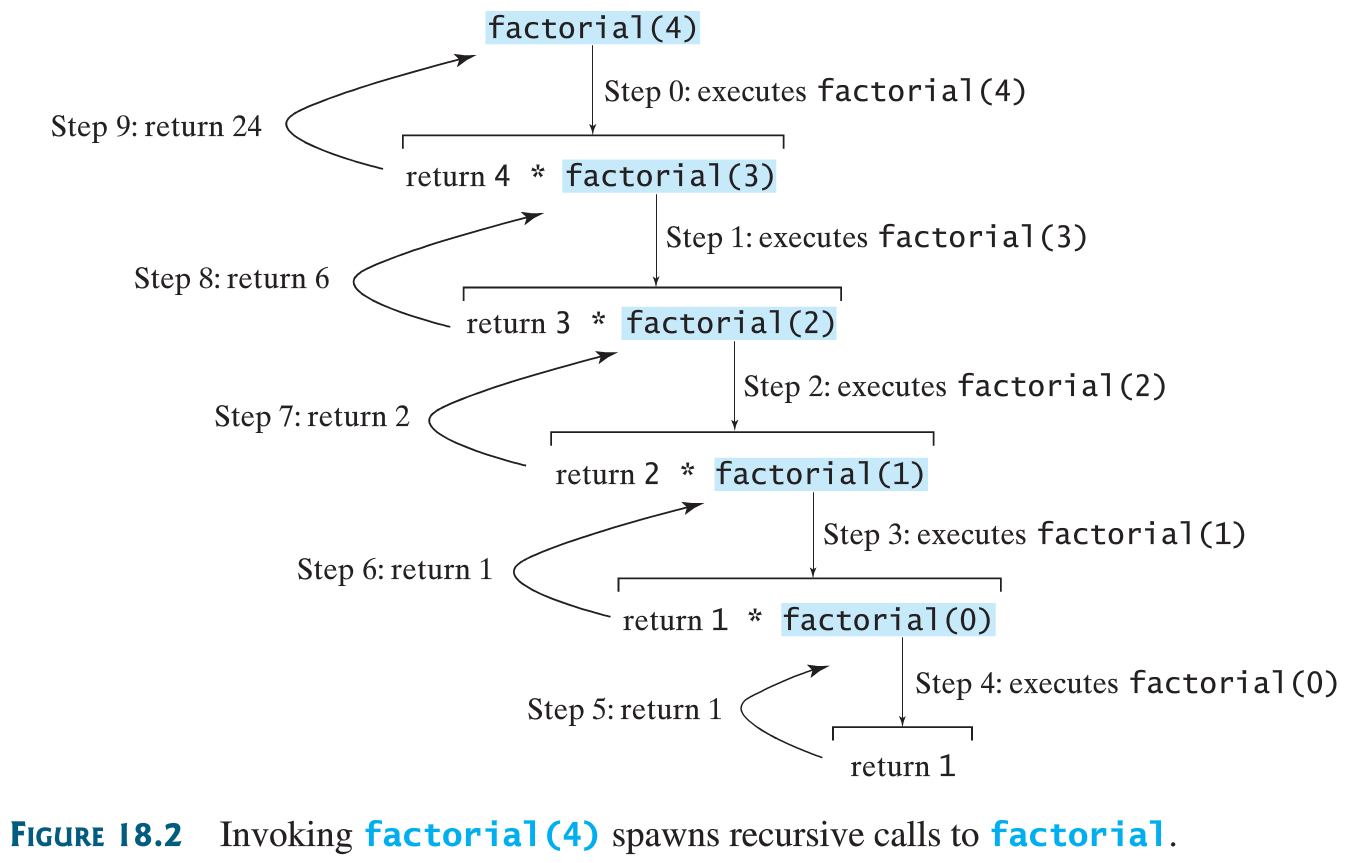

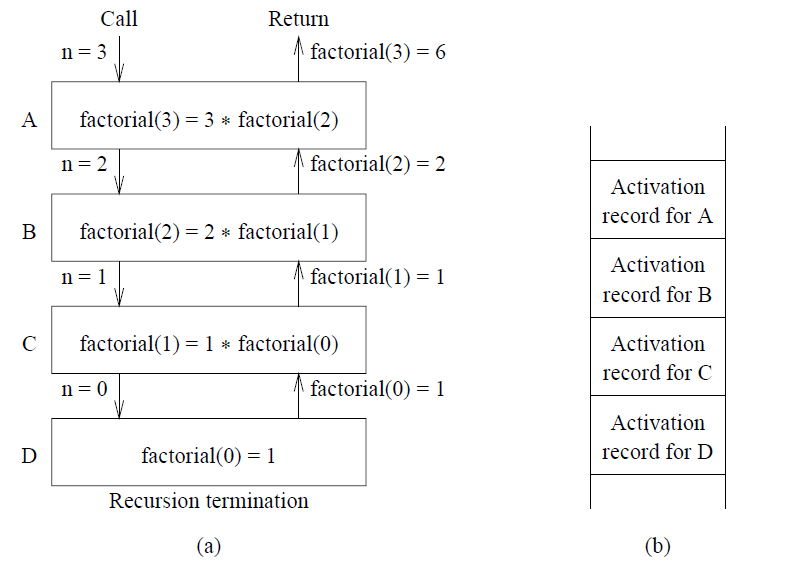

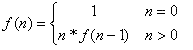

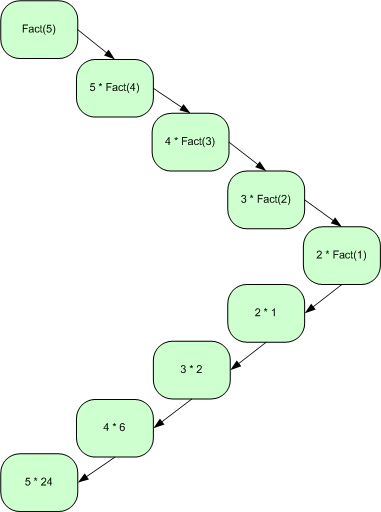

Recursive case:

n! = n * ((n - 1)!)

Base case (termination):

0! = 1

Condition/test, which checks for the base:

if(n == 0):

Observe code

Example:

Factorial n! = n * ((n - 1)!)

0! = 1

Observe code, and evaluate calling factorial of 3.

Python:

Recursion/python/recursion_02_factorial.py

#!/usr/bin/python3

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

"""

Factorial.

For example, factioral(5) is:

5! = 5 * 4 * 3 * 2 * 1

"""

import math

print(math.factorial(5))

# %% Recursive

def factorial_rec(n: int) -> int:

"Computes n! for positive n integers"

if n == 0:

return 1

else:

return n * factorial_rec(n - 1)

for n in range(1, 11):

val = factorial_rec(n)

print(n, " factorial is ", val)C++

Recursion/cpp/Recursion02Factorial.cpp

/**

Various implementations of factorial.

**/

#include <iostream>

#include "astack.h"

#include <exception>

using namespace std;

double factorial(int n, string indent = "") {

double result;

cout << indent << "Calling factorial with n = " << n << endl;

if (n > 1) {

// can just return instead if you don't want fancy print immediately below

result = n * factorial(n - 1, indent += " ");

cout << indent << "Unwinding factorial with n = " << n

<< ", and result = " << result << endl;

} else if (n < 0) // undefined

{

throw exception();

} else {

result = 1;

}

return result;

}

double factorialTail(int n, int sum = 1, string indent = "") {

cout << indent << "Calling factorial with n = " << n << " and sum = " << sum

<< endl;

// error condition

if (n < 0) {

throw exception();

} else if (1 == n) {

return sum;

}

// Tail recursive call

return factorialTail(n - 1, n * sum, indent += " ");

// We can't cout anything on the way back up the stack

}

// Iterative Factorial using loops (imperative), accumulate pattern

double factorialLoop(int n) {

double total = 1;

for (int i = 1; i < n + 1; i++) {

total *= i;

cout << "FactLoop n = " << n << " and i = " << i << " and total = " << total

<< endl;

}

return total;

}

// three outside variables are referenced by the loop: total, i, and n

// Loop turned into a tail recursive function

double factLoopRec(int n, double total = 1, int i = 1) {

cout << "FactTail2 n = " << n << " and i = " << i << " and total = " << total

<< endl;

if (i < (n + 1))

return factLoopRec(n, total * i, i + 1);

else

return total;

}

// replacing recursion with a stack (uses stack class above)

// We'll cover this later

long long factStack(int n, Stack<double> &S) {

while (n > 1) {

S.push(n--);

}

long long result = 1;

while (S.length() > 0) {

cout << "factStack n = " << n << " and result = " << result << endl;

result = result * S.pop();

}

return result;

}

int main() {

int n;

cout << "Enter a number to find factorial: ";

cin >> n;

cout << "Factorial middle recursive: " << n << " = " << factorial(n) << endl

<< endl;

cout << "Factorial tail recursive: " << n << " = " << factorialTail(n) << endl

<< endl;

cout << "Factorial loop: " << n << " = " << factorialLoop(n) << endl << endl;

cout << "Factorial factLoopRec: " << n << " = " << factLoopRec(n) << endl

<< endl;

AStack<double> stk(50);

cout << "Factorial factStack: " << n << " = " << factStack(n, stk) << endl

<< endl;

return 0;

}Haskell:

Recursion/haskell/Recursion02Factorial.hs

#!/usr/bin/runghc

module Recursion02Factorial where

import Data.List

-- Four different versions of Factorial(n):

factInf :: Int -> Integer

factInf n = product (take n [1 ..])

factRec :: Integer -> Integer

factRec 0 = 1

factRec n = n * factRec (n - 1)

factTail :: Integer -> Integer -> Integer

factTail 0 sum = sum

factTail n sum = factTail (n - 1) (n * sum)

factFoldl :: Integer -> Integer

factFoldl n = foldl' (*) 1 [1 .. n]

main :: IO ()

main = do

print (factInf 5)

print (factInf 10)

print (factRec 5)

print (factRec 10)

print (factTail 5 1)

print (factTail 10 1)

print (factFoldl 5)

print (factFoldl 10)Since 3 is not 0, take second branch and calculate (n-1)!...

Since 2 is not 0, take second branch and calculate (n-1)!...

Since 1 is not 0, take second branch and calculate (n-1)!...

Since 0 equals 0, take first branch and return 1.

Return value, 1, is multiplied by n = 1, and return result.

Return value, 1, is multiplied by n = 2, and return result

Return value, 2, is multiplied by n = 3, and the result, 6, becomes the

return value of the function call that started the whole process.

What happens when I run this??

As you can see, recursion is the bomb!

Python:

Recursion/python/recursion_03_uh_o.py

#!/usr/bin/python3

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

"""

Created on Sat Dec 3 18:16:57 2016

@author: taylor@mst.edu

Recursion is the bomb!

"""

def recursion_lecture(day: int) -> None:

print("Learning recursion", day)

return recursion_lecture(day + 1)

day = 0

recursion_lecture(day)Haskell:

Recursion/haskell/Recursion03Bomb.hs

#!/usr/bin/runghc

module Recursion03Bomb where

recursionLecture :: Int -> String -> String

recursionLecture day indent = indent ++ " More recursion\n" ++ recursionLecture (day + 1) (indent ++ " ")

main :: IO ()

main = do

putStrLn (take 500 (recursionLecture 0 ""))“Wherever you go, there you are.”

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jon_Kabat-Zinn

Recursive side note:

One concrete definition of consciousness or awareness is

meta-cognition,

a form of self-referential thought.

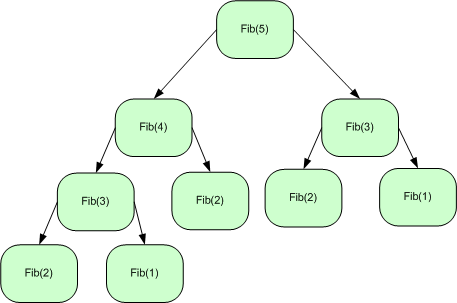

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Call_stack

Manages the stack of activation records.

A Call stack is a stack data structure that stores

information,

about the active subroutine (function) call in a computer program.

A call is implemented by storing data about the subroutine onto

“the stack”.

(including the return address, parameters, and local variables)

It is also known as:

the execution stack, program stack, control stack, run-time stack, or

machine stack,

and is often shortened to just “the stack”.

Information associated with one function call is stored,

and called an activation record or stack

frame.

Further subroutine calls add more records / frames to the stack.

Each return from a subroutine pops the top activation record off the

stack.

Call stack data is important for the proper functioning of most

software.

Details are normally hidden and automatic in high-level programming

languages.

In a most languages, it is managed invisibly “behind the

scenes”,

though you can directly inspect or manipulate it, if you want.

You can peek into the back-end by using pudb,

gdb, or ghci to see the stack.

When viewing the stack:

Which activation records are most shallow,

and which are most deep?

Observe these while tracing:

Each record on the stack needs a return address (more on this in years to come).

In practice, a recursive call doesn’t make an entire new copy of a

routine.

Each function call is assigned a chunk of memory,

to store its activation record where it:

Records the location to which it will return.

Re-enters the new function code at the beginning.

Allocates memory for the local data for this new invocation of the

function.

… until the base case, then:

Returns to the earlier function right after where it left off…

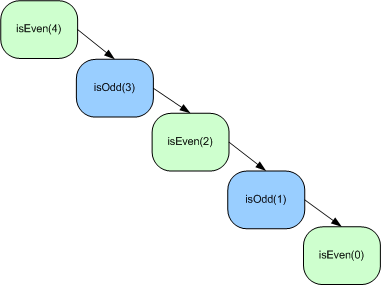

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Recursion_(computer_science)#Types_of_recursion

Recursive programming variations: a partial

overview

Single recursion:

Contains a single self-reference

e.g., list traversal, linear search, or computing the factorial

function…

Single recursion can often be replaced by an iterative

computation,

running in linear (n) time and requiring constant space.

Multiple recursion (binary included):

Contains multiple self-references,

e.g., tree traversal, depth-first search (coming up in future

courses)…

This may require exponential time and space, and is more fundamentally

recursive,

not being able to be replaced by iteration without an explicit

stack.

Multiply recursive algorithms may seem more inherently recursive.

Some of the slowest complexity-class functions known are multiply

recursive;

some were even designed to be slow!

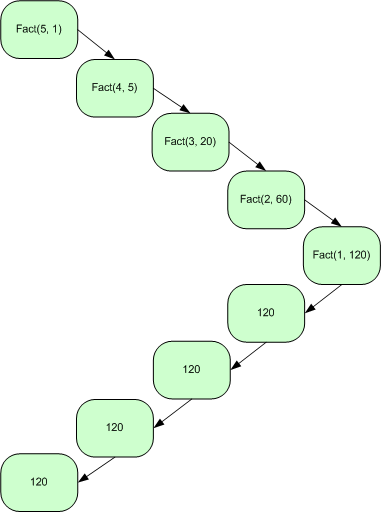

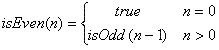

Indirect (or mutual) recursion:

Occurs when a function is called not by itself,

but by another function that it called (either directly or

indirectly).

Chains of 2, 3, …, n functions are possible.

Generative recursion:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Recursion_(computer_science)#Structural_versus_generative_recursion

Acts on outputs it generated (e.g., a mutated mutable List).

Structural recursion:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Structural_induction

Acts on progressive newly generated sets of input data (e.g., a copied

immutable string).

Co-recursion:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corecursion

Infinite, lazy, recursion with no base case.

A single linear self-reference.

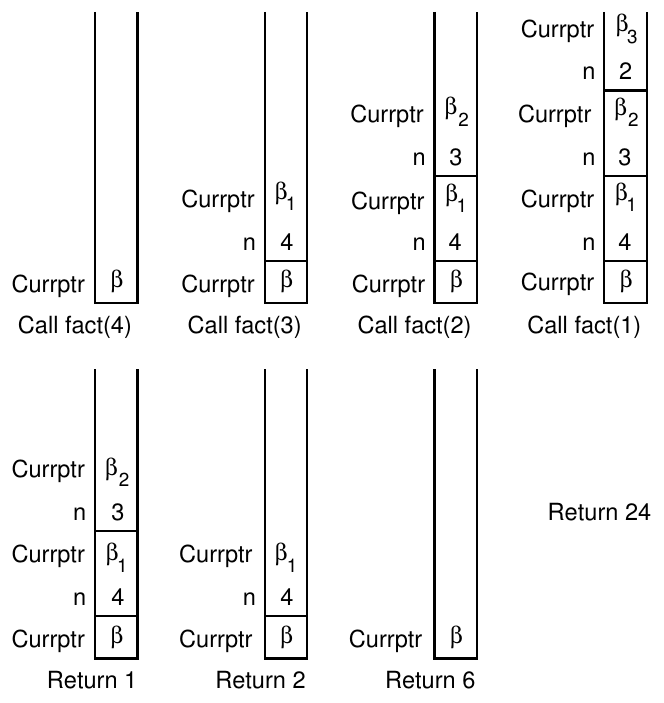

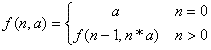

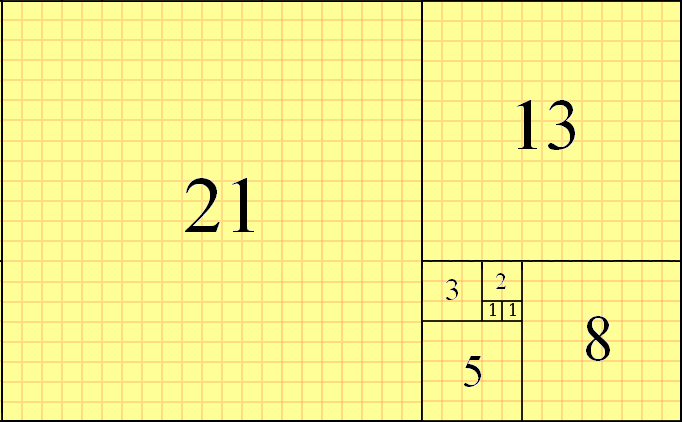

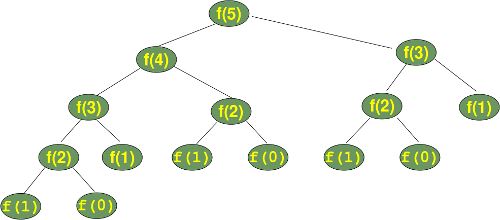

As above, this is another way to define factorial:

The first line is the base case.

The second line is the recursive call.

Notice that the recursive call to f() does NOT contain all

statements.

Specifically n * resides outside the call.

Example call-tree for factorial definition:

Where the recursive call contains all computation, and mimics iteration.

Factorial definition with tail-call design:

The first line is the base case.

The second line is the recursive case.

Notice that the recursive call to f() contains all statements,

with none outside f().

This mimics an iterative construction in some way.

Example call-tree for tail-call factorial definition:

This is potentially more efficient.

A function that calls a friend, that calls it back.

A pair of functions that each return a Boolean:

This is an inefficient way to check for even or odd numbers…

To expand on that side note, check out the code.

Python:

Recursion/python/recursion_04_thats_odd.py

#!/usr/bin/python3

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

"""

Created on Sat Dec 3 18:16:57 2016

@author: taylor@mst.edu

"""

def is_even(no: int) -> bool:

print("Calling isOdd with: ", no)

if 0 == no:

return True

else:

return is_odd(no - 1)

def is_odd(no: int) -> bool:

print("Calling isOdd with: ", no)

if 0 == no:

return False

else:

return is_even(no - 1)

for n in range(10):

# OK but comprehensible way to detect even/odd

if n % 2 == 0:

print(n, "is even")

else:

print(n, "is odd")

# Fastest way with bitwise operator

# (just & with last bit, not whole number division)

if n & 1 == 0:

print(n, "is even")

else:

print(n, "is odd")

# A terribly ineffecient way to detect even/odd

if is_even(n):

print(n, "is even")

else:

print(n, "is odd")C++:

Recursion/cpp/Recursion04EvenOdd.cpp

/**

Mutual recursion

**/

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

bool isOdd(int no);

bool isEven(int no) {

cout << "Calling isEven with: " << no << endl;

if (0 == no)

return true;

else

return isOdd(no - 1);

}

bool isOdd(int no) {

cout << "Calling isOdd with: " << no << endl;

if (0 == no)

return false;

else

return isEven(no - 1);

}

int main() {

int number;

cout << "Input an integer" << endl;

cin >> number;

if (isEven(number))

cout << "Your number is even" << endl;

else

cout << "Your number is odd" << endl;

return 0;

}Haskell:

Recursion/haskell/Recursion04EvenOdd.hs

#!/usr/bin/runghc

module Recursion04EvenOdd where

import Data.Bits

isEven :: Int -> Bool

isEven 0 = True

isEven n = isOdd (n - 1)

isOdd :: Int -> Bool

isOdd 0 = False

isOdd n = isEven (n - 1)

main :: IO ()

main = do

putStrLn "Slowest:"

print (isEven 10)

print (isEven 5)

print (isOdd 10)

print (isOdd 5)

putStrLn "\nLess slow:"

print (mod 10 2 == 0)

print (mod 5 2 == 0)

print (mod 10 2 /= 0)

print (mod 5 2 /= 0)

putStrLn "\nFastest:"

print ((10 :: Int) .&. 1 == 0)

print ((5 :: Int) .&. 1 == 0)

print ((10 :: Int) .&. 1 /= 0)

print ((5 :: Int) .&. 1 /= 0)

putStrLn "\nBuilt in:"

print (even 10)

print (even 5)

print (odd 10)

print (odd 5)(a kind of multiple recursion)

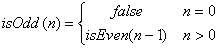

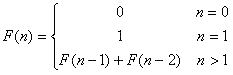

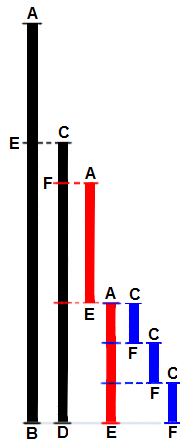

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fibonacci_number

Fibonacci sequence definition:

Base case:

F0 = 0,

F1 = 1

Recursive case:

Fn = Fn-1 + Fn-2

Unpacked:

1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, …

Functional set-notation definition:

What the call-tree could look like:

Do you see any problems here?

Wait on code trace for this function until efficiency section below.

“To create recursion, you must create recursion.”

First design and write the base case(s) and the

conditions to check it!

You must always have some base case(s), which can be solved without

recursion.

Combine the results of one or more smaller, but similar,

sub-problems.

If the algorithm you write is correct,

then certainly you can rely on it (recursively) to solve the smaller

sub-problems.

You’re not just decomposing it into parts, but incrementally smaller

parts.

Make real progress

For the cases that are to be solved recursively,

the recursive call must always be to a future case,

that makes a fixed quantity of progress toward a base

case (not fixed proportion).

What happens if you always get half closer to something?

Check progressively larger inputs,

to inductively validate that there is no infinite recursion

Proof of correctness by induction?

Can you satisfy to yourself that it works on a problem of size 0, 1, 2,

3, …, n?

Do not worry about how the recursive call solves the

sub-problem.

Simply accept that it will solve it correctly,

and use this result to in turn correctly solve the original

problem.

Compound interest guideline:

Try not to duplicate work,

by not solving the same instance of a problem repeatedly,

in separate recursive calls.

Of recursion in code.

There are a variety of ways to reverse an ordered container.

We can use recursion to use the input/output buffer to reverse inputted

text.

Recall, variables operated on before the recursive call appear on the

way down the stack,

while those operated on after the recursive call appear after the base

case,

on the way up the stack.

Remember, as we unwind off the stack,

the values of the variables are where we left them.

Check out code now examples now.

Python:

Recursion/python/recursion_05_reverse.py

#!/usr/bin/python3

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

"""

Word reversal.

"""

# Basic iterable reversal:

"astr"[::-1]

# reversed function

"".join(list(reversed("astr")))

# reversed with list comp

"".join([char for char in reversed("astr")])

# Manually with a loop:

mystr = "astr"

accumstring = ""

for ichar in range(len(mystr) - 1, -1, -1):

accumstring += mystr[ichar]

# %% Simple string reversal

def reverse_me(s: str) -> str:

"Reverses a string, and returns nothing."

if s == "":

return s

else:

return reverse_me(s[1:]) + s[0]

print("Enter something you'd like backwards:")

print(reverse_me("taxes"))

# %% Simple string reversal with tab trick

def reverse_me_indent(s: str, indent: str = " ") -> str:

"Reverses a string, and returns nothing."

print(indent, "Starting another call with:", s)

if s == "":

return s

else:

return reverse_me_indent(s[1:], indent + " ") + s[0]

print("\nEnter something you'd like backwards:")

print(reverse_me_indent("evil"))C++:

Recursion/cpp/Recursion05Reverse.cpp

/**

Simple word reversal

**/

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void reverseMe() {

char ch;

cin.get(ch);

if (ch != '\n') {

reverseMe();

cout.put(ch); // after recursive statement means what?

}

}

int main() {

cout << "Enter something you would like backwards: ";

// how about taxes?

reverseMe();

return 0;

}Haskell:

Recursion/haskell/Recursion05Reverse.hs

#!/usr/bin/runghc

module Recursion05Reverse where

import Data.List

-- This one is inefficient

reverseMe :: [a] -> [a]

reverseMe [] = []

reverseMe (x : xs) = reverseMe xs ++ [x]

reverseEff :: [a] -> [a] -> [a]

reverseEff [] new = new

reverseEff (x : xs) new = reverseEff xs (x : new)

reverseFoldl :: [a] -> [a]

reverseFoldl = foldl' (\acc x -> x : acc) []

reverseFlip :: [a] -> [a]

reverseFlip = foldl' (flip (:)) []

main :: IO ()

main = do

putStrLn (reverse "evil")

putStrLn (reverseMe "taxes")

putStrLn (reverseEff "backwards" [])

putStrLn (reverseFoldl "reverse")

putStrLn (reverseFlip "park")

-- boobytraphttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palindrome

Base case (which often results in

termination)?

If we assume that we must have incrementally smaller versions of the

problem,

then does this lead us to our base case?

Is the string ’’ a palindrome?

is the string ‘a’ a palindrome?

Recursive case?

What is the one-smaller version of a palindrome problem?

Do we work from the inside or outside?

What is the condition/test that checks for the base?

What is a check for a one-smaller version of the palindrome problem?

Observe code to show recursion stack.

Python:

Recursion/python/recursion_06_palindrome.py

#!/usr/bin/python3

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

"""

Recursive palindrome

"""

def is_palindrome_rec(s: str) -> bool:

"Returns True if s is a palindrome and False otherwise."

if len(s) <= 1:

return True

else:

return s[0] == s[-1] and is_palindrome_rec(s[1:-1])

print(is_palindrome_rec("racecar"))

# Quitting early?

print(is_palindrome_rec("racecat"))

print(is_palindrome_rec("able was I ere I saw elba"))

# %% Recursive palindrome with better output

def is_palindrome_rec_out(s: str, indent: str = " ") -> bool:

"""

Returns True if s is a palindrome and False otherwise,

With nice stack illustration.

"""

print(indent, "called with: ", s)

if len(s) <= 1:

print(indent, "base case")

return True

else:

ans = s[0] == s[-1] and is_palindrome_rec_out(s[1:-1], indent + " ")

print(indent, "About to return: ", ans)

return ans

# Note: This algorithm handles odd and even strings just fine

# (think about base case)

print(is_palindrome_rec_out("racecar"))

print(is_palindrome_rec_out("racecat"))

print(is_palindrome_rec_out("tacocat"))

print(is_palindrome_rec_out("anutforajaroftuna"))

print(is_palindrome_rec_out("able was I ere I saw elba"))

print(is_palindrome_rec_out("neveroddoreven"))

# https://www.grammarly.com/blog/16-surprisingly-funny-palindromes/Cool side-note: we use greedy boolean comparisons to quit early (efficiently)!

C++:

Recursion/cpp/Recursion06IsPalindrome.cpp

/**

Palindrome detector

Examples:

able was i ere i saw elba

racecar

**/

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

bool isPalindrome(string input, string indent = "") {

bool result;

string in = input;

cout << indent << in << endl;

// why don't we use == 1 ?

if (in.length() <= 1) {

result = true;

} else {

// what happens for an almost palindrome (middle mismatch)

result = ((in[0] == in[in.length() - 1]) &&

isPalindrome(input.substr(1, in.length() - 2), indent += " "));

cout << indent << in << endl;

}

return result;

}

int main() {

cout << "Enter a palindrome: " << endl;

string input;

getline(cin, input);

if (isPalindrome(input)) {

cout << "That is a palindrome" << endl;

} else {

cout << "That is NOT a palindrome" << endl;

}

return 0;

}Haskell:

Recursion/haskell/Recursion06IsPalindrome.hs

#!/usr/bin/runghc

module Recursion06IsPalindrome where

import Data.List as L

import Data.Vector as V

isPalindromeRev :: (Eq a) => [a] -> Bool

isPalindromeRev xs = xs == L.reverse xs

isPalindromeRec :: (Eq a, Show a) => Vector a -> Bool

isPalindromeRec xs =

V.length xs == 1

|| let lastPos = (V.length xs - 1)

firstElem = xs V.! 0

lastElem = xs V.! lastPos

in firstElem == lastElem && isPalindromeRec (V.slice 1 (lastPos - 1) xs)

main :: IO ()

main = do

print (isPalindromeRev "a")

print (isPalindromeRev "racecar")

print (isPalindromeRev "racecat")

print (isPalindromeRec (V.fromList "a"))

print (isPalindromeRec (V.fromList "racecar"))

print (isPalindromeRec (V.fromList "racecat"))++++++++++++++++++

Cahoot-14.3

The GCD of two numbers (AB and CD) is illustrated below.

It is the largest number that divides both without leaving a remainder

(CF).

Euclid’s algorithm efficiently computes the greatest common divisor

(GCD).

Proceeding left to right:

Check out the code, loop then recursive.

Python:

Recursion/python/recursion_07_gcd.py

#!/usr/bin/python3

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

"""

Greatest Common Divisor using Euclid's Algorithm

"""

# %% GCD loop

def gcd_loop(a: int, b: int) -> int:

"Return the Greatest Common Divisor of a and b using Euclid's Algorithm"

while a != 0:

a, b = b % a, a

return b

print(gcd_loop(10, 15))

# %% CGD recursive

def gcd_rec(a: int, b: int) -> int:

"Return the Greatest Common Divisor of a and b using Euclid's Algorithm"

if b == 0:

return a

else:

return gcd_rec(b, a % b)

print("The GCD of 10 and 15 is:")

print(gcd_rec(10, 15))C++:

Recursion/cpp/Recursion07GCD.cpp

/**

GCD using both a loop and recursion.

**/

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

// Euclid's non-recursive method for GCD:

long long gcdLoop(long long dividend, long long divisor) {

while (divisor != 0) {

long long remainder = dividend % divisor;

cout << "Dividend = " << dividend << ", divisor = " << divisor

<< ", remainder =" << remainder << endl;

dividend = divisor;

divisor = remainder;

}

return dividend;

}

// Tail Recursive GCD

long long gcdRec(const long long dividend, const long long divisor) {

long long remainder = dividend % divisor;

cout << "Dividend = " << dividend << ", divisor = " << divisor

<< ", remainder =" << remainder << endl;

if (remainder == 0)

return divisor;

else

return gcdRec(divisor, remainder);

}

int main() {

cout << "gcdLoop: " << gcdLoop(24212, 238) << endl << endl;

cout << "gcdRec: " << gcdRec(24212, 238) << endl << endl;

return 0;

}Haskell:

../../Security/Content/AffineCipher/CryptoMath.hs

module CryptoMath where

-- |

-- >>> gcd' 55 30

-- 5

gcd' :: Int -> Int -> Int

gcd' a b =

if mod a b == 0

then b

else gcd' b (mod a b)

-- |

-- >>> modInv 5 66

-- Just 53

-- |

-- >>> modInv 6 66

-- Nothing

modInv :: Int -> Int -> Maybe Int

modInv a m

| 1 == g = Just (mkPos i)

| otherwise = Nothing

where

(i, _, g) = gcdExt a m

mkPos x

| x < 0 = x + m

| otherwise = x

-- Extended Euclidean algorithm.

-- Given non-negative a and b, return x, y and g

-- such that ax + by = g, where g = gcd(a,b).

-- Note that x or y may be negative.

gcdExt :: Int -> Int -> (Int, Int, Int)

gcdExt a 0 = (1, 0, a)

gcdExt a b =

let (q, r) = quotRem a b

(s, t, g) = gcdExt b r

in (t, s - q * t, g)../../Security/Content/AffineCipher.html#gcd

Which is more efficient, and by how much?

After 2 iterations, rem is at half its original value.

If ab > cd, then ab % cd < ab / 2.

Thus, the number of iterations is at most log n.

++++++++++++++++++

Cahoot-14.4

Add all the numbers in a list of ints.

Recursive case: What is an incrementally smaller version of the sum

problem?

Base case: What is the smallest termination condition?

Count all the numbers in a list of ints.

Recursive case: What is an incrementally smaller version of the count

problem?

Base case: What is the smallest termination condition?

See code: Iterative versus Recursive.

Python:

Recursion/python/recursion_08_sum_count.py

#!/usr/bin/python3

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

"""

Sum more recursion...

"""

# %% Sum Iterative

def sum_loop(my_list: list[int]) -> int:

"Iterative sum"

accum_sum = 0

# Add every number in the list.

for i in range(0, len(my_list)):

accum_sum = accum_sum + my_list[i]

# Return the sum.

return accum_sum

print(sum_loop([5, 7, 3, 8, 10]))

# %% Sum Recursive

def sum_rec(my_list: list[int]) -> int:

"Recursive sum"

if len(my_list) == 1:

return my_list[0]

else:

return my_list[0] + sum_rec(my_list[1:])

print(sum_rec([5, 7, 3, 8, 10]))

# %% count/length Recursive

def count_rec(my_list: list[int]) -> int:

"Recursive count/length"

if len(my_list) == 1:

return 1

else:

return 1 + count_rec(my_list[1:])

print(count_rec([5, 7, 3, 8, 10]))Could we convert from the iterative version to the recursive?

Haskell:

Recursion/haskell/Recursion08SumCount.hs

#!/usr/bin/runghc

module Recursion08SumCount where

sumRec :: (Num a) => [a] -> a

sumRec [] = 0

sumRec (x : xs) = x + sumRec xs

sumFld :: (Num a) => [a] -> a

sumFld xs = foldr (+) 0 xs

cntRec :: (Num a) => [a] -> a

cntRec [] = 0

cntRec (_ : xs) = 1 + cntRec xs

main :: IO ()

main = do

print (sum [1 .. 10])

print (sumRec [1 .. 10])

print (sumFld [1 .. 10])

print (length [1 .. 10])

print (cntRec [1 .. 10])“Progress isn’t made by early risers.

It’s made by lazy men trying to find easier ways to do

something.”

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_A._Heinlein

Are there any disadvantages to recursion?

What overhead is involved when making a function call?

save caller’s state

allocate stack space for arguments

allocate stack space for local variables

invoke routine at exit (return), release resources

restore caller’s “environment”

resume execution of caller

Much of this is language-dependent.

A few (but not all) recursive functions can be unnecessarily

inefficient,

and would be better implemented as iterative functions.

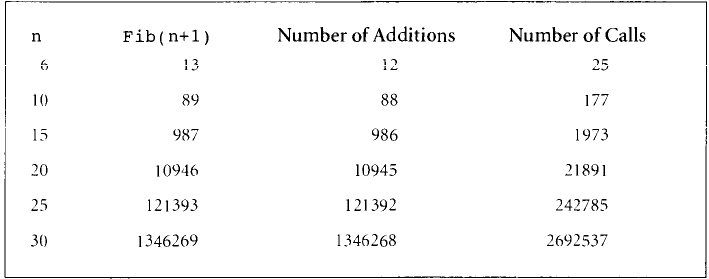

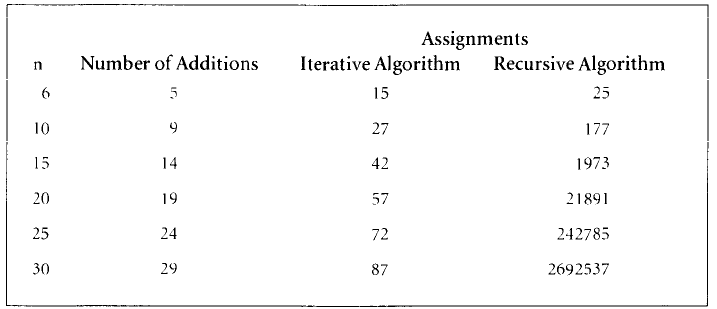

Our first recursive Fibonacci implementation is inefficient,

and has a steep computational complexity than our iterative

solution,

no fibbing:

if n is zero, then fib(n) is: 0if n is one, then fib(n) is: 1

else, fib(n) is: fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2)

Observe recursive code.

Python:

Recursion/python/recursion_09_loop_to_recursion_fibonacci.py

#!/usr/bin/python3

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

"""

Efficiency discusion using fibonacci sequence:

f(n) = f(n - 2) + f(n - 1)

= 1 if n == 0 or n == 1

"""

# fibonacci using a loop

def fib_loop(n: int) -> int:

"Computes first n fib numbers, using loop"

a, b = 0, 1 # the first and second Fibonacci numbers

for i in range(n):

a, b = b, a + b

return a

print(fib_loop(10))

# recursive Fibonacci (inefficient)

def fib_rec(n: int) -> int:

"""Return Fibonacci of x, where x is a non-negative int"""

if n < 2:

return n # or 1

else:

return fib_rec(n - 1) + fib_rec(n - 2)

print(fib_rec(10))

# %% Tail recursion

# %% tail recursive fibonacci (efficient)

def fib_rec_tail(n: int, previous: int = 0, current: int = 1, i: int = 0) -> int:

"""

Computes first n fib numbers, using tail recursion

Another way of defaulting values.

This is both more sensible and more dangerous,

since the user can break it.

"""

if i < n:

return fib_rec_tail(n, current, previous + current, i + 1)

else:

return previous

print(fib_rec_tail(10))

# %% tail recursive fibonacci (efficient)

def fib_rec_tail_wrapped(n: int) -> int:

"""

Computes first n fib numbers, using tail recursion

One way of defaulting values, which hides the values.

"""

def go(previous: int, current: int, i: int) -> int:

if i < n:

return go(current, previous + current, i + 1)

else:

return previous

return go(0, 1, 0)

print(fib_rec_tail_wrapped(10))Step f(3) all the way deep.

When you step a multiply recursive line, which gets called first, left

or right?

This algorithm produces something like a depth-first enumeration of the

above tree.

While it is nice that the python code looks like our mathematical

definition, it is inefficient!

How long does fib_rec(35) take?

How many iterations?

C++:

Recursion/cpp/Recursion09Fibonacci.cpp

/**

Fibonacci

f(n) = f(n-2) + f(n-1)

= 0 or 1 if n == 0 or n == 1

**/

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

// recursive Fibonacci (inefficient)

double fibonacci(int n) {

if (n == 0)

return 0;

else if (n == 1)

return 1;

else

return fibonacci(n - 1) + fibonacci(n - 2);

}

double fibonacci2(int n) {

if (n < 2)

return n;

else

return fibonacci(n - 1) + fibonacci(n - 2);

}

// fibonacci using a loop (efficient)

double fibonacciLoop(int n) {

int i; // the loop variable

double previous = 0; // the first Fibonacci number

double current = 1; // the second Fibonacci number

// n steps

for (i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

double temp = previous + current;

previous = current;

current = temp;

}

return previous;

}

// fib loop converted to tail recursive, is efficient

double fibConvert(int n, double previous = 0, double current = 1, int i = 0) {

if (i < n)

return fibConvert(n, current, previous + current, i + 1);

else

return previous;

}

// Global cache...

int fibo_cache[100] = {0};

// this batch array initialization syntax only works for 0s

// memoization/caching improves efficiency

double fibonacciCached(int n) {

if (fibo_cache[n] == 0) {

if (n < 2) {

fibo_cache[n] = n;

return n;

} else {

fibo_cache[n] = fibonacciCached(n - 1) + fibonacciCached(n - 2);

}

}

return fibo_cache[n];

}

int main() {

for (int i = 1; i < 44; i++)

cout << "FibRec of " << i << " = " << fibonacci(i) << endl;

for (int i = 1; i < 44; i++)

cout << "FibLoop of " << i << " = " << fibonacciLoop(i) << endl;

for (int i = 1; i < 44; i++)

cout << "fibConvert of " << i << " = " << fibConvert(i) << endl;

for (int i = 0; i < 30; i++)

cout << fibo_cache[i] << ", ";

for (double i = 1; i < 44; i++)

cout << "fibonacciCached of " << i << " = " << fibonacciCached(i) << endl;

return 0;

}Haskell:

Recursion/haskell/Recursion09Fibonacci.hs

#!/usr/bin/runghc

module Recursion09Fibonacci where

-- This version is not efficient.

-- It re-computes values it already computed

fibRec :: Int -> Integer

fibRec 0 = 0

fibRec 1 = 1

fibRec n = fibRec (n - 1) + fibRec (n - 2)

-- The versions below are efficient:

fibTail :: Integer -> Integer -> Integer -> Integer -> Integer

fibTail n previous current i

| i < n = fibTail n current (previous + current) (i + 1)

| otherwise = previous

fibWrapExternal :: Integer -> Integer

fibWrapExternal n = fibTail n 0 1 0

fibWrapInternal :: Integer -> Integer

fibWrapInternal n =

let go n previous current i =

if i < n

then fibTail n current (previous + current) (i + 1)

else previous

in go 10 0 1 0

main :: IO ()

main = do

print (fibRec 10)

print (fibTail 10 0 1 0)

print (fibWrapExternal 10)

print (fibWrapInternal 10)

How long does fib_loop(35) take?

How many iterations?

There are a number of solutions to this problem of efficiency:

If you can easily find a looping algorithm

(e.g., Fibonacci with a loop below)

Observe iterative code.

The larger the n, the worse the recursive solution becomes,

in comparison to the iterative.

This is what it means to have a worse complexity.

Remember, recursion is just another way to loop.

Designing an iterative algorithm to replace a recursive one is not

always easily possible.

Tail recursion is much like looping.

Often, but not always, developing tail recursive implementation,

may follow first writing an iterative solution.

++++++++++++++++++

Cahoot-14.5

“There is nothing so useless as doing efficiently that which

should not be done at all.”

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Drucker

is just a glorified loop.

Tail call is a subroutine call performed as the final action of a

procedure

(recall order mattering example).

Tail calls don’t have to add new stack frame to the call stack.

Tail recursion is a special case of recursion,

where the calling function does no more computation after making a

recursive call.

Tail-recursive functions are functions in which all recursive calls are

tail calls,

and thus do not build up any deferred operations.

Producing such optimized code instead of a standard call sequence is

called tail call elimination.

Tail call elimination allows procedure calls in tail position to be

implemented efficiently,

as goto statements, thus allowing more efficient structured

programming.

converts an iterative loop into a tail recursion.

Systematic steps:

First identify those variables that exist outside the loop,

but are changing in the loop body;

these variable will become formal parameters in the recursive

function.

Then build a function that has these “outside” variables as

formal parameters,

with default initial values.

The original loop test becomes an if() test in the body of the new function.

The if-true block becomes the needed statements within the loop and the recursive call.

Arguments to the recursive call encode the updates to the loop variables.

else block becomes either the return of the value the loop attempted to calculate (if any), or just a return.

Conversion results in tail recursion.

Code examples:

See multiple examples in code (fib, fact, countdown),

match them to the above steps in detail.

This is really cool.

It is a systematic way to convert any loop to recursion,

by just following those above steps in rote form!

Python:

Recursion/python/recursion_10_loop_to_recursion_factorial.py

#!/usr/bin/python3

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

"""

Created on Sat Dec 3 18:16:57 2016

@author: taylor@mst.edu

"""

# %% Iterative Factorial using loops (imperative), accumulate pattern

def fact_loop(n: int) -> int:

"Computes the factorial of n, returns n."

total = 1

for i in range(1, n + 1):

total *= i

return total

print(fact_loop(5))

# %% tail recursive factorial

def fact_rec_tail(n: int) -> int:

"""

Computes the factorial of n, returns n.

One way of defaulting value, which hides the details.

"""

def loop(total: int, i: int) -> int:

if i < n + 1:

return loop(total * i, i + 1)

else:

return total

return loop(1, 1)

print(fact_rec_tail(5))

# %% tail recursive factorial

def fact_rec_tail2(n: int, total: int = 1, i: int = 1) -> int:

"""

Computes the factorial of n, returns n.

Another way of defaulting values.

"""

if i < n + 1:

return fact_rec_tail2(n, total * i, i + 1)

else:

return total

print(fact_rec_tail2(5))C++:

See above.

Haskell:

See above.

Recursion/python/recursion_11_loop_to_recursion_countdown.py

#!/usr/bin/python3

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

"""

Countdown

"""

# %% Countdown loop

def countdown_for_loop(i: int) -> None:

"countdown from i using iteration"

for counter in range(i, 0, -1):

print(counter, " ")

countdown_for_loop(5)

# %% Countdown tail

def countdown_tail(i: int) -> None:

"countdown from i using recursion"

def loop(counter: int) -> None:

if 0 < counter:

print(counter, " ")

loop(counter - 1)

loop(i)

countdown_tail(5)

# %% Countdown loop

def countdown_while_loop(i: int) -> None:

"countdown from i using iteration"

while 0 < i:

print(i, " ")

i -= 1

countdown_while_loop(5)

# %% Countdown tail

def countdown_tail_natural(i: int) -> None:

if i > 0:

print(i, " ")

countdown_tail_natural(i - 1)

countdown_tail_natural(5)

"""

Concluding remarks:

Unfortunately, Python is not a good language in this regard.

When the value of a recursive call is immediately returned

(i.e., not combined with some other value),

a function is said to be tail recursive.

The Haskell, Scheme, Clojure programming languages optimize tail recursive functions,

so that they are just as efficient as loops both in time and in space utilization.

"""Haskell:

Recursion/haskell/Recursion11Countdown.hs

#!/usr/bin/runghc

module Recursion11Countdown where

countDown :: Int -> String

countDown 0 = "\n"

countDown n = show n ++ "\n" ++ countDown (n - 1)

countDownTabbed :: Int -> String -> String

countDownTabbed 0 indent = indent ++ "\n"

countDownTabbed n indent = indent ++ show n ++ "\n" ++ countDownTabbed (n - 1) (indent ++ " ") ++ indent ++ "after\n"

main :: IO ()

main = do

putStrLn (countDown 10)

putStrLn (countDownTabbed 10 "")A future lab in this class will involve solving several problems

iteratively and recursively.

For each problem, you will implement one iterative solution and one

recursive solution.

To program the recursive solution, you could either:

Implement a natural recursive solution by inventing one creatively, or

Implement an iterative solution,

and then perform the above systematic conversion,

to use tail-call recursion from your iterative solution.

Language choice gcc-c++ (aka g++) can usually do tail call

optimization.

Tail call elimination doesn’t automatically happen in Java or

Python,

though it does reliably in functional languages like Lisps:

Haskell, Scheme, Clojure (upon specification with recur

only), and Common Lisp,

which are designed to employ this kind of recursion.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Memoization

Memoization and caches (stores) values,

which have already been computed,

rather than re-compute them.

It speeds up computer programs,

by storing the results of expensive function calls,

and returning the cached result when the same inputs occur again.

See code for Fibonacci

Python:

Recursion/python/recursion_12_memoization_dynamic_prog.py

#!/usr/bin/python3

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

"""

Created on Sat Dec 3 18:16:57 2016

@author: taylor@mst.edu

"""

from functools import lru_cache

from typing import Optional

# %% Recall, fib is slow with recursion

# memoization specific to the problem is a fix

def fib_memo(n: int, memo: dict[int, int]) -> int:

"""

Computes the first n fib numbers.

"""

if n not in memo:

memo[n] = fib_memo(n - 1, memo) + fib_memo(n - 2, memo)

return memo[n]

memo: dict[int, int] = {0: 0, 1: 1}

print(fib_memo(35, memo))

# %% memoizatino v2 (general)

def fib_memo_gen(n: int, fib_cache: Optional[dict[int, int]] = None) -> int:

"""

Return Fibonacci of x, where x is a non-negative int

Hides the memoiziation from the user!

"""

if fib_cache is None:

fib_cache = {}

if n in fib_cache:

return fib_cache[n]

if n < 2:

return n # or 1

else:

value = fib_memo_gen(n - 1, fib_cache) + fib_memo_gen(n - 2, fib_cache)

fib_cache[n] = value

return value

print(fib_memo_gen(35))

# %% memoization v3 (Python general)

@lru_cache(maxsize=1000)

def fib_memo_lru(n: int) -> int:

"""

Return Fibonacci of x, where x is a non-negative int

Uses a decorator memoization method

"""

if n < 2:

return n # or 1

else:

return fib_memo_lru(n - 1) + fib_memo_lru(n - 2)

print(fib_memo_lru(35))C++:

See Fibonacci above (has memoization example).

Haskell:

Recursion/haskell/Recursion12Memoization.hs

#!/usr/bin/runghc

module Recursion12Memoization where

slowFib :: Int -> Integer

slowFib 0 = 0

slowFib 1 = 1

slowFib n = slowFib (n - 2) + slowFib (n - 1)

memoizedFib :: Int -> Integer

memoizedFib =

let fib 0 = 0

fib 1 = 1

fib n = memoizedFib (n - 2) + memoizedFib (n - 1)

in (Prelude.map fib [0 ..] !!)

main :: IO ()

main = do

print (slowFib 10)

print (memoizedFib 10)This kind of memoization is a form of dynamic

programming,

which is really a terrible name, because it’s much more like static

programming:

one definition (there are others) is that you store values instead of

re-computing them,

in a trade-off between space complexity (storage) and time complexity

(CPU cycles):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dynamic_programming#Computer_programming

In the trace, load up a full dictionary for fib_mem,

which does something like a depth-first population of the

dictionary!

This is the most recursion-friendly solution so far,

and works for essentially any recursive program,

even those that can’t easily be converted to a loop.

Conversion of recursive functions to loops is:

less systematic than converting a loop to tail recursive,

requires more creativity, and

isn’t always easy for a human,

though converting an already tail recursive algorithm is more

straightforward.

Often converting more inherently recursive algorithms to loops,

requires keeping a programmer-designed stack,

like would be done by the compiler in the first place.

See example for factorial (C++).

“Life can only be understood backwards;

but it must be lived forwards.”

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/S%C3%B8ren_Kierkegaard

Recursion is not just for toy examples.

What kind of algorithms are realistically implemented using

recursion?

There are many algorithms that are simpler or easier to program

recursively,

for example tree enumeration algorithms.

Tree traversal is the most common real-world use of recursion.

Some recursive algorithms are actually more efficient (for example,

exponentiation).

Some algorithms were invented recursively,

and no one has figured out an equivalent iterative algorithm

(other than a trivial stack conversion like the compiler or interpreter

uses).

What about some more realistic algorithm?

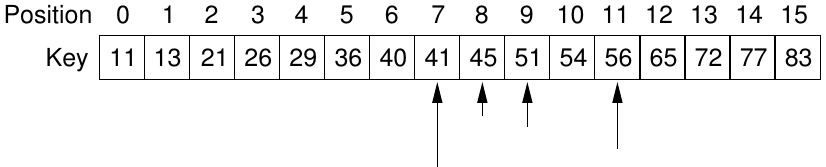

We covered binary search using loops on our last lecture:

AlgorithmsSoftware.html

How might we implement this form of search recursively?

What is the base case?

What is the incrementally smaller case?

What is the condition?

See code now.

Python:

Recursion/python/recursion_13_binary_search.py

#!/usr/bin/python3

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

"""

Binary search implemented with recursion.

"""

# %% Find element in list using binary search

# During the last class before recursion,

# we covered binary search iteratively

def bin_search_rec(

lst: list[int], item: int, low: int, high: int, indent: str = ""

) -> int:

"""

Finds index of string in list of strings, else -1.

Searches only the index range low to high

Note: Upper/Lower case characters matter

"""

print(indent, "find() range", low, high)

range_size = (high - low) + 1

mid = (high + low) // 2

if item == lst[mid]:

print(indent, "Found number.")

pos = mid

elif range_size == 1:

print(indent, "Number not found.")

pos = -1

else:

if item < lst[mid]:

print(indent, "Searching lower half.")

pos = bin_search_rec(lst, item, low, mid, indent + " ")

else:

print(indent, "Searching upper half.")

pos = bin_search_rec(lst, item, mid + 1, high, indent + " ")

print(indent, "Returning pos = %d." % pos)

return pos

nums = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

pos = bin_search_rec(nums, 9, 0, len(nums) - 1)

if pos >= 0:

print("\nFound at position %d." % pos)

else:

print("\nNot found.")Haskell:

AlgorithmsSoftware/AlgBinarySearch.hs

#!/usr/bin/runghc

module AlgBinarySearch where

import Data.Vector as V

binarySearchWhere :: (Ord a) => V.Vector a -> a -> Int -> Int -> Maybe Int

binarySearchWhere coll element lo hi

| hi < lo = Nothing

| pivot < element = binarySearchWhere coll element (mid + 1) hi

| element < pivot = binarySearchWhere coll element lo (mid - 1)

| otherwise = Just mid

where

mid = lo + div (hi - lo) 2

pivot = coll V.! mid

binarySearchLet :: (Ord a) => V.Vector a -> a -> Int -> Int -> Maybe Int

binarySearchLet coll element lo hi =

let mid = lo + div (hi - lo) 2

pivot = coll V.! mid

in if hi < lo

then Nothing

else case compare pivot element of

LT -> binarySearchLet coll element (mid + 1) hi

GT -> binarySearchLet coll element lo (mid - 1)

EQ -> Just mid

main :: IO ()

main = do

print (binarySearchWhere (V.fromList [1 .. 30]) 30 0 29)

print (binarySearchWhere (V.fromList ['a' .. 'z']) 'g' 0 29)

print (binarySearchWhere (V.fromList [1, 3 .. 30]) 4 0 29)

putStrLn ""

print (binarySearchLet (V.fromList [1 .. 30]) 30 0 29)

print (binarySearchLet (V.fromList ['a' .. 'z']) 'g' 0 29)

print (binarySearchLet (V.fromList [1, 3 .. 30]) 4 0 29)https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Backtracking

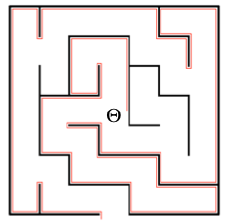

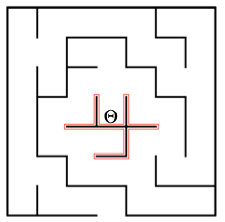

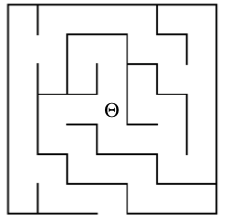

Backtracking finds all (or some) solutions to some computational

problems,

notably constraint satisfaction problems,

by incrementally building candidates to the solutions,

and abandoning a candidate (“backtracking”),

as soon as it determines that the candidate as bad,

because it cannot possibly be completed as a valid solution.

It is actually what is known as a general

meta-heuristic,

rather than an algorithm:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metaheuristic

This is in-part because you can use the meta-heuristic to wrap

algorithms,

for a variety of problems, with slight modifications.

How do you fix your past mistakes??

You are faced with repeated sequences of options and must choose one

each step.

After you make your choice you will get a new set of options.

Which set of options you get depends on which choice you made.

Procedure is repeated until you reach a final state.

If you made a good sequence of choices, your final state may be a goal

state.

If you didn’t, you can go back and try again.

For example, games such as:

n-Queens, Knapsack problem, Sudoku, Maze, etc.

Backtracking is a general meta-heuristic.

It incrementally builds candidate solutions,

by a sequence of candidate extension steps, one at a time,

and abandons each partial candidate, c, (by backtracking),

as soon as it determines that c cannot possibly be extended to a valid

solution.

can be completed in various ways,

to give all the possible solutions to the given problem.

can be implemented with a form of recursion, or stacks to mimic

recursion.

refers to the following procedure:

If at some step it becomes clear that the current path is bad,

because it can’t lead to a solution,

then you go back to the previous step (backtrack) and choose a different

path.

Pick a starting point.

recursive_function(starting point)

If you are done (base case), then

return True

For each move from the starting point,

If the selected move is valid,

select that move,

and make recursive call to rest of problem.

If the above recursive call returns True, then

return True.

Else

undo the current move

If none of the moves work out, then

return FalseYou can use this meta-heuristic to solve a whole variety of problem types.

++++++++++++++++++

Cahoot-14.6

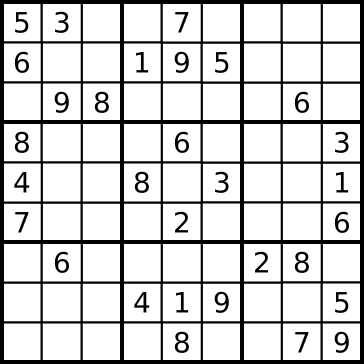

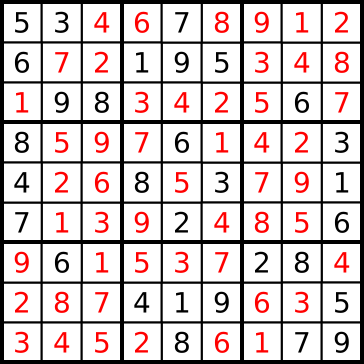

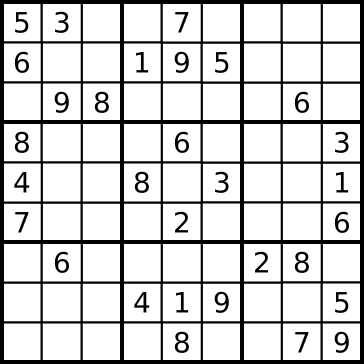

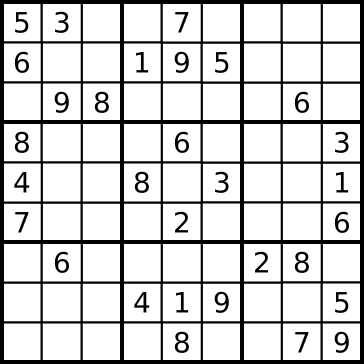

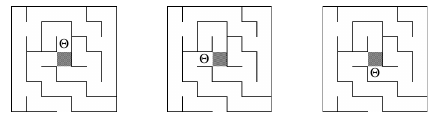

We’ll go over Sudoku and maze-navigation now:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sudoku

Starting board (not initial configurations all are solvable, but this

one is):

Finish (win):

Board is 81 cells, in a 9 by 9 grid.

with 9 zones, each zone being:

the intersection of the first, middle, or last 3 rows,

and the first, middle, or last 3 columns.

Each cell may contain a number from one to nine;

each number can only occur once in each zone, row, and column of the

grid.

At the beginning of the game, some cells begin with numbers in

them,

and the goal is to fill in the remaining cells.

Exercises:

What would be your human Sudoku strategies?

How might we solve this non-recursively (iteratively)?

Where would you start?

What might you loop across?

How would you end?

What sub-functions might you want?

How about recursively?

What is the base case?

What is an incrementally smaller version?

What is the condition/check?

Which functions do we need?

Do they overlap from the iterative version we drafted above?

recursive_sudoku()

Find row, col of an unassigned cell, an open move

If there are no free cells, a win, then

return True

For digits from 1 to 9

If no conflict for digit at (row, col), then

assign digit to (row, col)

recursively try to fill rest of grid

If recursion successful, then

return True

Else

remove digit

If all digits were tried, and nothing worked, then

return FalseCode for Sudoku.

Python:

Recursion/python/recursion_14_sudoku.py

#!/usr/bin/python3

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

"""

Sudoku solver.

"""

# UNASSIGNED is used for empty cells in grid (a constant)

UNASSIGNED = 0

def solve_sudoku(grid: list[list[int]], indent: str = "") -> bool:

"""

Takes a partially filled-in grid and attempts to assign values to all

unassigned locations in such a way as to meet the requirements for Sudoku:

non-duplication across rows, columns, and zones

"""

row_col: list[int] = []

# If there is no unassigned location, we are done

# Otherwise, row and col are modified

# (since they are passed by ref)

if not find_unassigned_location(grid, row_col):

# Total sucess

return True

row, col = row_col

# consider digits 1 to 9

for num in range(1, 10):

# Does this digit produce any immediate conflicts?

if is_safe(grid, row, col, num):

# make tentative assignment

grid[row][col] = num

print(indent, "grid[", row, "]", "[", col, "] = ", num, sep="")

# return, if success, yay!

if solve_sudoku(grid, indent + " "):

# like it occurs after recursive call

return True

else:

# failure, un-do (backtrack) and try again

grid[row][col] = UNASSIGNED

print(indent, "grid[", row, "]", "[", col, "] = 1-9 all conflict!", sep="")

# this triggers backtracking

return False

def find_unassigned_location(grid: list[list[int]], row_col: list[int]) -> bool:

"""

Searches the grid to find an entry that is still unassigned. If found, the

reference parameters row, col will be end up set (by the for loop) to the

location that is unassigned, and true is returned. If no unassigned entries

remain, false is returned.

"""

for row in range(len(grid)):

for col in range(len(grid[0])):

if grid[row][col] == UNASSIGNED:

row_col[:] = row, col

return True

return False

def used_in_row(grid: list[list[int]], row: int, num: int) -> bool:

"""

Returns a boolean which indicates whether any assigned entry in the

specified row matches the given number.

"""

for col in range(len(grid[0])):

if grid[row][col] == num:

return True

return False

def used_in_col(grid: list[list[int]], col: int, num: int) -> bool:

"""

Returns a boolean which indicates whether any assigned entry in the

specified column matches the given number.

"""

for row in range(len(grid)):

if grid[row][col] == num:

return True

return False

def used_in_box(

grid: list[list[int]], box_start_row: int, box_start_col: int, num: int

) -> bool:

"""

Returns a boolean which indicates whether any assigned entry within the

specified 3x3 box matches the given number.

"""

for row in range(3):

for col in range(3):

if grid[row + box_start_row][col + box_start_col] == num:

return True

return False

def is_safe(grid: list[list[int]], row: int, col: int, num: int) -> bool:

"""

Returns a boolean which indicates whether it will be legal to assign num to

the given row,col location. Check if 'num' is not already placed in

current row, current column and current 3x3 box

"""

return (

not used_in_row(grid, row, num)

and not used_in_col(grid, col, num)

and not used_in_box(grid, row - row % 3, col - col % 3, num)

)

def print_grid(grid: list[list[int]]) -> None:

"""

Prints the grid.

"""

for row in grid:

for element in row:

print(element, " ", end="")

print()

def main() -> None:

# 0 for unassigned cells, as the constant at top

grid = [

[3, 0, 6, 5, 0, 8, 4, 0, 0],

[5, 2, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 8, 7, 0, 0, 0, 0, 3, 1],

[0, 0, 3, 0, 1, 0, 0, 8, 0],

[9, 0, 0, 8, 6, 3, 0, 0, 5],

[0, 5, 0, 0, 9, 0, 6, 0, 0],

[1, 3, 0, 0, 0, 0, 2, 5, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 7, 4],

[0, 0, 5, 2, 0, 6, 3, 0, 0],

]

print("Problem is:")

print_grid(grid)

print("Solution is:")

if solve_sudoku(grid):

print_grid(grid)

else:

print("No solution exists")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()Note: I originally wrote this for C++, and then converted it to

python,

so this python code has a bit of a C-style to it.

C++:

Recursion/cpp/Recursion14Sudoku.cpp

/**

A Backtracking program to solve the Sudoku puzzle

**/

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

// UNASSIGNED is used for empty cells in grid

const int UNASSIGNED = 0;

// N is used for size of Sudoku grid. Size is NxN

const int N = 9;

// Finds an entry in grid that is still unassigned, if any:

bool FindUnassignedLocation(int grid[N][N], int &row, int &col);

// Checks whether it is legal to assign num to the given row,col

bool isSafe(int grid[N][N], int row, int col, int num);

/* Takes a partially filled-in grid and attempts to assign values to

all unassigned locations in such a way as to meet the requirements

for Sudoku: non-duplication across rows, columns, and zones */

bool SolveSudoku(int grid[N][N], string indent = "") {

int row, col;

// If there is no unassigned location, we are done

// Otherwise, row and col are modified

// (since they are passed by ref)

if (!FindUnassignedLocation(grid, row, col))

return true; // Total success!

// consider digits 1 to 9

for (int num = 1; num <= 9; num++) {

// Does this digit produce any immediate conflicts?

if (isSafe(grid, row, col, num)) {

// make tentative assignment

grid[row][col] = num;

cout << indent << "grid[" << row << "]" << "[" << col << "] = " << num

<< endl;

// return, if success, yay!

if (SolveSudoku(grid, indent + " "))

return true; // like it occurs after recursive call

// failure, un-do (backtrack) and try again

grid[row][col] = UNASSIGNED;

}

}

cout << indent << "grid[" << row << "]" << "[" << col

<< "] = " << "1-9 all conflict!" << endl;

return false; // this triggers backtracking

}

/* Searches the grid to find an entry that is still unassigned. If

found, the reference parameters row, col will be end up set

(by the for loop) to the location that is unassigned,

and true is returned. If no unassigned entries remain,

false is returned. */

bool FindUnassignedLocation(int grid[N][N], int &row, int &col) {

for (row = 0; row < N; row++)

for (col = 0; col < N; col++)

if (grid[row][col] == UNASSIGNED)

return true; // What happens to rol and col here?

return false;

}

/* Returns a boolean which indicates whether any assigned entry

in the specified row matches the given number. */

bool UsedInRow(int grid[N][N], int row, int num) {

for (int col = 0; col < N; col++)

if (grid[row][col] == num)

return true;

return false;

}

/* Returns a boolean which indicates whether any assigned entry

in the specified column matches the given number. */

bool UsedInCol(int grid[N][N], int col, int num) {

for (int row = 0; row < N; row++)

if (grid[row][col] == num)

return true;

return false;

}

/* Returns a boolean which indicates whether any assigned entry

within the specified 3x3 box matches the given number. */

bool UsedInBox(int grid[N][N], int boxStartRow, int boxStartCol, int num) {

for (int row = 0; row < 3; row++)

for (int col = 0; col < 3; col++)

if (grid[row + boxStartRow][col + boxStartCol] == num)

return true;

return false;

}

/* Returns a boolean which indicates whether it will be legal to assign

num to the given row,col location. */

bool isSafe(int grid[N][N], int row, int col, int num) {

/* Check if 'num' is not already placed in current row,

current column and current 3x3 box */

return !UsedInRow(grid, row, num) && !UsedInCol(grid, col, num) &&

!UsedInBox(grid, row - row % 3, col - col % 3, num);

}

/* Print grid */

void printGrid(int grid[N][N]) {

for (int row = 0; row < N; row++) {

for (int col = 0; col < N; col++)

cout << grid[row][col] << " ";

cout << endl;

}

cout << endl;

}

int main() {

// 0 for unassigned cells

int grid[N][N] = {{3, 0, 6, 5, 0, 8, 4, 0, 0}, {5, 2, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0},

{0, 8, 7, 0, 0, 0, 0, 3, 1}, {0, 0, 3, 0, 1, 0, 0, 8, 0},

{9, 0, 0, 8, 6, 3, 0, 0, 5}, {0, 5, 0, 0, 9, 0, 6, 0, 0},

{1, 3, 0, 0, 0, 0, 2, 5, 0}, {0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 7, 4},

{0, 0, 5, 2, 0, 6, 3, 0, 0}};

cout << "Problem: " << endl;

printGrid(grid);

cout << "Solution: " << endl;

if (SolveSudoku(grid) == true)

printGrid(grid);

else

cout << "No solution exists";

return 0;

}Haskell:

Recursion/haskell/Recursion14Sudoku.hs

#!/usr/bin/runghc

module Recursion14Sudoku where

import Data.List as L

import Data.Vector as V

exampleGrid :: Vector (Vector Int)

exampleGrid =

V.fromList

( Prelude.map

V.fromList

[ [3, 0, 6, 5, 0, 8, 4, 0, 0],

[5, 2, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 8, 7, 0, 0, 0, 0, 3, 1],

[0, 0, 3, 0, 1, 0, 0, 8, 0],

[9, 0, 0, 8, 6, 3, 0, 0, 5],

[0, 5, 0, 0, 9, 0, 6, 0, 0],

[1, 3, 0, 0, 0, 0, 2, 5, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 7, 4],

[0, 0, 5, 2, 0, 6, 3, 0, 0]

]

)

tinyGrid :: Vector (Vector Int)

tinyGrid =

V.fromList

( Prelude.map

V.fromList

[ [1, 2],

[3, 4]

]

)

-- |

-- >>> renderGrid tinyGrid

-- "[1,2]\n[3,4]"

renderGrid :: Vector (Vector Int) -> String

renderGrid grid = L.intercalate "\n" (toList (V.map show grid))

-- |

-- >>> inRow exampleGrid 0 6

-- True

-- |

-- >>> inRow exampleGrid 0 7

-- False

inRow :: Vector (Vector Int) -> Int -> Int -> Bool

inRow exampleGrid row num = V.elem num (exampleGrid V.! row)

-- |

-- >>> inCol exampleGrid 1 8

-- True

-- |

-- >>> inCol exampleGrid 1 6

-- False

inCol :: Vector (Vector Int) -> Int -> Int -> Bool

inCol exampleGrid col num = V.elem num (V.map (V.! col) exampleGrid)

-- |

-- >>> inBox exampleGrid 0 0 2

-- True

-- |

-- >>> inBox exampleGrid 0 0 11

-- False

inBox :: Vector (Vector Int) -> Int -> Int -> Int -> Bool

inBox grid startRow startCol num =

let box = V.map (V.slice startCol 3) (V.slice startRow 3 grid)

in V.any id (V.map (V.elem num) box)

-- |

-- >>> isSafe exampleGrid 0 0 2

-- False

-- |

-- >>> isSafe exampleGrid 0 0 11

-- True

isSafe :: Vector (Vector Int) -> Int -> Int -> Int -> Bool

isSafe grid row col num =

not (inRow grid row num) && not (inCol grid col num) && not (inBox grid (row - mod row 3) (col - mod col 3) num)

-- |

-- >>> firstEmpty exampleGrid 0

-- Just (0,1)

-- |

-- >>> firstEmpty exampleGrid 1

-- Just (1,2)

firstEmpty :: Vector (Vector Int) -> Int -> Maybe (Int, Int)